Attempt to reduce carbon emissions from housing risk running into multiple ‘Yellow Vest’ moments unless housing is made a social good, not a for-profit asset.

Julieta Perucca is an experienced human rights advocate, previously working alongside the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to housing. She is now the co-founder and Deputy Director of The Shift, a human rights organization working at the intersection of housing, finance, and climate change.

Cross-posted from the Green European Journal

The housing and climate crises are caught in a vicious circle.

The housing sector is responsible for around one-fifth of global carbon emissions, exacerbating climate change through both the energy used to run homes and the energy consumed in construction and demolition. This contributes to a warming and unpredictable climate, which makes housing more expensive or unhealthy due to excess heat, rising insurance costs or worse. Climate-fueled disasters have already become the leading driver of internal displacement, forcing around 20 million people a year from their homes. As the sea level rises, natural disasters increase in frequency and scale, and climate change fuels drought and conflict, researchers estimate that 1.2 billion people could be displaced globally by 2050.

While the Global South is set to bear the biggest brunt, Europe will be affected too. Not only will its countries have to deal with the direct effects of climate change on its own population, but they will also have to manage an influx of climate refugees. This comes amid an ongoing housing crisis, both globally and within the EU, where more than one in ten people were spending over 40 per cent of their disposable income on housing in 2021.

Addressing the mutually reinforcing crises of housing and climate change is urgently needed, and Europe has a plan to cut buildings’ greenhouse gas emissions by 60 per cent within the end of the decade.

Addressing the mutually reinforcing crises of housing and climate change is urgently needed, and Europe has a plan to cut buildings’ greenhouse gas emissions by 60 per cent within the end of the decade. Since buildings are responsible for 36 per cent of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions, reaching these targets will be crucial to hitting overall climate objectives. But if these targets are approached in the wrong way, they could exacerbate the housing crisis and inequality.

More efficient, more expensive?

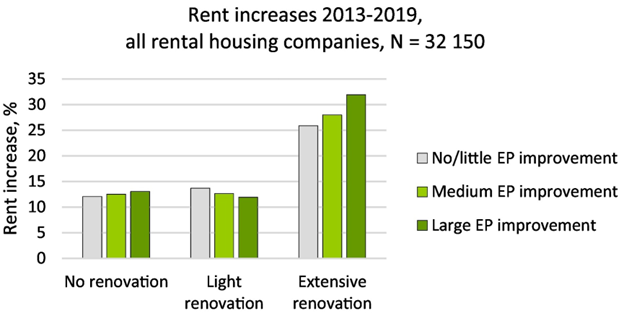

It is often said that energy-efficient renovations deliver long-term cost savings to tenants since they reduce the costs of heating and cooling. But studies show a much more nuanced reality. In Sweden, where landlords pay heating costs, researchers looked at what really happened to tenants whose homes underwent energy retrofitting projects between 2013 and 2019.

The good news was that modest eco-friendly renovations successfully translated into financial relief for tenants. Yet, for larger-scale projects, the financial burden noticeably shifted to renters. Low-income tenants, whose homes are often less energy-efficient and most likely to need renovations to meet minimum EU energy performance requirements, disproportionally had to bear the financial burden. Specifically, households that underwent extensive green renovations saw rents – including heating costs – surge by over 30 per cent. Compare this to a 12 per cent uptick in the rental prices for dwellings without any renovations. And for homes under private ownership, significant green renovations skyrocketed rents by 40 per cent on average.

“We must question whether societal cost-efficiency […] can be fairly achieved by disproportionately letting low-income households carry part of the cost without compensatory measures,” write the authors of the study, suggesting that investigating the cost burden is particularly urgent amid increasing inequality, decreasing access to affordable housing, and growing pressure for extensive energy retrofitting in low-income housing.

[Average rent increases at different levels of energy performance (EP) improvement in different renovation categories in Sweden. Rent increases correspond to the net change in rent levels and energy costs for heating, as the latter are included in the rent.

Source: Jenny von Platten, et al. Energy Research & Social Science Volume 92, October 2022, 102791]

We should view these findings in the broader European context. Given Sweden’s relatively stringent rent regulations and the fact that 60 per cent of its renters resided in public housing in 2022, this same effect is likely to be even more pronounced in countries where the private sector has a greater hold on the housing market and leeway to increase rents or even use the familiar tactic of “renovictions” to maximise profits. Shedding light on housing affordability issues is all the more urgent amid the renovation wave, which is a key part of the European Green Deal.

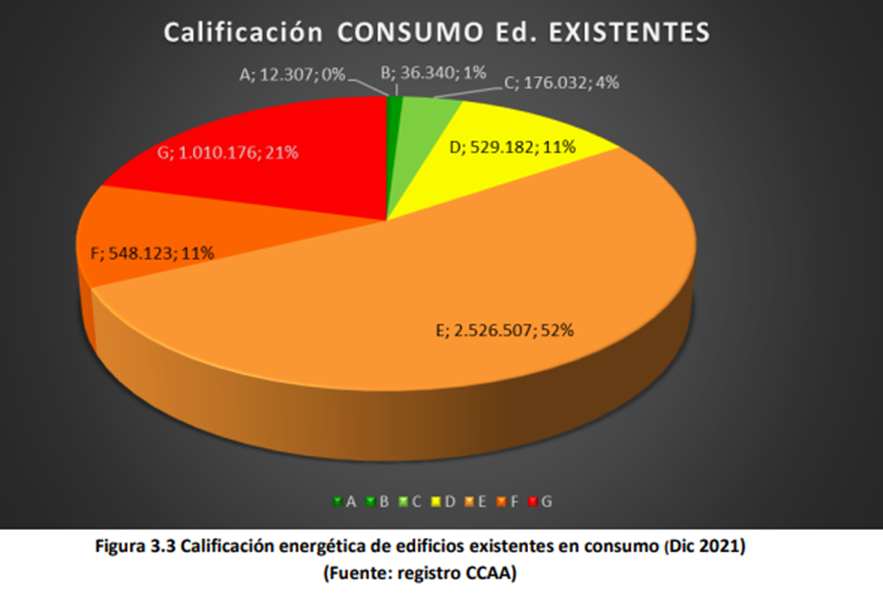

In Spain for instance, most renters already spend more than 30 per cent of their income on housing. There, the housing stock will likely have to undergo major renovations to comply with the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), which is still under negotiation. According to government records of homes with energy ratings, more than 80 per cent of Spanish homes would need to be renovated to comply with the European Parliament’s proposed energy performance minimums before they are rented or sold after 2033. Without strict rent controls or limitations, this could become a nightmare situation for many tenants.

[Energy consumption of existing buildings in Spain with energy performance ratings. Under the new EPBD, the European Parliament proposes that residential buildings would need to reach class D by 2033, though a limited set of exemptions would apply to certain categories of buildings like public social housing. Source: Spain’s Energy Ministry.]

Research from the US reflects a parallel concern about improvements to wider communities. One study focusing on the city of Philadelphia found that green resilient infrastructure, while commendable, may inadvertently hike the risk of gentrification in lower-income neighbourhoods, displacing the poorest to climate vulnerable areas.

A quagmire for politicians

Improving housing emissions is already becoming a politically fraught issue in Europe. In Germany, polls suggest that a bill to ban new oil and gas heating systems as early as 2024 cost the Green Party major support in the polls. Critics said the move could plunge citizens into poverty because low-income people simply can’t afford the upfront investment in heat pumps. The so-called “boiler ban” bill was eventually watered down. Even so, it still faced criticism from the conservative opposition and actors ahead of its approval by the Bundestag on 8 September.

But Andree Boehling, an energy expert at Greenpeace, warns that the climate crisis can’t wait. “Any energy expert will tell you that it’s patently clear that this revised bill – in its current state – will result in Germany failing to hit its 2030 climate protection targets,” he told NPR.

At the same time, the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (FEANTSA) warns in its 2022 report on housing exclusion about green renovations driving inequality in Germany. While landlords are getting loans and subsidies from the German public bank to make homes more efficient, the right to a “modernisation levy” allows them to jack up rents by up to 8 per cent to compensate, which can burden tenants and lead to “renovictions”.

Dividends on homelessness

Within the current market dynamics, societies are basically left with the choice of either achieving housing goals or environmental targets. But it doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game. What is needed is to move beyond the current model of financialised housing.

The financialisation of housing – viewing homes not for their social function but for their capacity to generate profits – has been instrumental to the global housing framework largely since the dawn of neoliberalism in the 1970s. Its modern, more aggressive incarnation is even younger, rooted in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. That’s when institutional investors pounced on the spat of mortgage foreclosures, using and creating new financial instruments to purchase thousands of homes at deep discounts.

Homes became an increasingly enticing asset class in Europe and elsewhere. In Berlin, for instance, institutional landlords like Vonovia, Blackstone, and pension funds gobbled up more than 40 billion euros worth of housing to rent out – a trend that only accelerated again during the pandemic. With homes having morphed into tools for enhancing revenues and shareholder dividends, the non-home-owning class has suffered, as soaring rents and home prices rise much faster than incomes. This model has displaced people from their communities, kept a generation of young people from being able to move out of their parents’ homes, and driven people into homelessness. The estimated number of people sleeping rough in the EU increased by around 70 per cent between 2010 and 2020.

Build, build, build?

Equally troubling is the fact that the financialisation of housing emerges as a direct contributor to the mounting climate crisis. A prevailing assumption among governments is that incentivising profit-centric entities to build more homes will essentially flood the market with new supply and curtail the affordability problem. But reality offers a stark contrast. Time and again, unregulated private actors, rather than building what’s needed, gravitate toward what’s most profitable – luxury housing instead of affordable homes.

The construction of homes can represent up to 75 per cent of a building’s carbon emissions from a typical 60-year life-cycle, so these developments are adding to global emissions and taking up outsized space in cities without responding to the affordability crisis. New economic thinkers estimate that if Europe is to stay within its carbon budget, the maximum number of households that can be built is just 176,000 per year. This is a shocking figure considering that Germany alone has pledged to build 400,000 new housing units per year.

Instead of a carbon-intensive model based on asking the private sector to “build, build, build,” we need to make the most of our existing structures. But financialisation often leads to the very opposite. Look at empty luxury apartments in cities around the globe – seen not as homes but as convenient ways to launder money or park cash to generate returns. In the London neighborhoods of Chelsea, Kensington and Westminster, the number of empty homes has more than doubled in ten years. According to 2021 census data, more than 25 per cent of the available dwellings were unoccupied, despite these being some of the most high-demand neighborhoods in the world. This is a testament to the wastefulness of the current system.

Adding to this are short-term rentals aiming to squeeze even more money out of homes. In Paris, for example, a staggering 86 per cent of Airbnb-listed properties are entire homes, yet they’re occupied for a mere 66 nights per year on average. This suggests that these homes in coveted locations, which so often displace locals, sit empty the vast majority of the time.

Institutional investors looking to buy existing homes tend to go after older, undervalued properties where they can increase rent after undertaking a renovation. Europe’s renovation wave is a perfect excuse to do so. As seen in Germany, these investors are often even entitled to tax-payer-funded subsidies.

The situation may seem dire. And it is. But it isn’t hopeless. I, alongside my colleagues Sam Freeman and Leilani Farha, have just published a Policy Guideline arguing that by tackling the financalisation of housing, societies can uphold the human right to housing and meet climate targets.

A paradigm shift

In Europe, where pivotal legislation is about to be passed around green housing, it is critical to understand the market forces that have shaped the housing market and not let them continue triumphing at the expense of the majority of citizens and the health of the planet. There’s no one silver policy bullet, but central to fixing the housing crisis is a paradigm shift. Instead of viewing homes as commodities that make people rich, they must be viewed as a human right. This is not a utopian ideal, but a legally binding obligation under international human rights law.

Governments at all levels can ensure this by enacting legislation that holds private investors accountable to the right to housing and a healthy environment. This should include reviewing and reforming all public benefits, licensing arrangements and policies geared towards providing preferential treatment to housing investors that are fueling the financialisation of housing. These benefits should be redirected to those actors who are substantially contributing to the development of affordable, sustainable housing stock, including non-market housing providers.

This should include transparent human rights and environmental assessments for new agreements or licensing. Since construction is such a huge part of emissions, high-emission construction for luxury or commodified housing should be avoided if we are to reach climate targets. All efforts to create supply should match housing demand, prioritising those experiencing the greatest level of vulnerability. Where there is deemed to be a need for new supply, it should be met by maximising the already existing built environment. New builds should be limited to green construction for the purposes of creating affordable housing.

Meanwhile, governments should consider expropriating or introducing mechanisms like taxes on financialised housing contributing to the twin problems of climate change and affordability – particularly units that sit empty as speculative investments or as short-term vacation rentals. Carrots should also be in place for actors who choose to reposition their units back into the long-term rental market.

Governments must lay out plans to decarbonise their housing systems in a way that respects human rights. Tenant protection and assistance will be key to moving forward, and should be a condition through which EU funding for renovations can be accessed. No-fault evictions and evictions into homelessness must be prohibited. Governments must also strictly regulate and monitor climate renovations, setting limits on the costs that can be passed onto tenants in accordance with a human rights framework, and ensuring that spurious upgrades are not being undertaken to simply renovict tenants. Tenant organisations could also be offered financial assistance to undertake climate-friendly renovations themselves, without having to rely on deep-pocketed investors or developers.

Other innovations are welcome, but the solutions are already within our reach. The current housing crisis was never inevitable, it is the result of a series of choices. And fixing it doesn’t mean giving up on climate goals either. All we need is the political will to address the core of what is fueling both crises – short-term profit-driven thinking that puts market interest before human rights and the environment.

Thanks to many generous donors BRAVE NEW EUROPE will be able to continue its work for the rest of 2023 in a reduced form. What we need is a long term solution. So please consider making a monthly recurring donation. It need not be a vast amount as it accumulates in the course of the year. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment