The war in Ukraine has brought the use of nuclear weapons into the realm of possibility. This article points out weaknesses in the logic of mutually assured destruction that underlies nuclear deterrence strategies. Instead, it proposes a treaty to impose sanctions on pre-emptive uses of nuclear weapons to establish a new international norm in which all citizens of the world share the power to decide the fate of the planet.

Keiichiro Kobayashi is Professor of Economics at Keio University

Cross-posted from VoxEU

All-out nuclear war is no longer only a theoretical possibility, and such an event would involve all of humankind. To follow Clemenceau’s ironic quote about war being too important to be left to the generals, the escalation of nuclear use and nuclear deterrence strategy is too directly related to our lives for us to ignore it and leave it to military and security experts. In this column, I examine the state of nuclear deterrence strategy as a story in which everyone could participate.

The logic of mutually assured destruction – i.e. “If a nuclear power is attacked with nuclear weapons, it will counterattack and destroy the other party and no one will survive. Therefore, no one will start a nuclear war” – is dangerous. There is a vulnerability and a perversion in this logic. For analyses on conflicts and nuclear deterrence in the framework of game theory, see Schelling (1960), Zagare (1992), and Kraig (1999).

First, the vulnerability: the logic of mutually assured destruction is correct in terms of game theory, but the assumptions behind the conclusions are too strong. The assumption is that, under perfect information, the players have full knowledge of their opponent’s behavioural objectives and that they will act fully rationally in accordance with their own behavioural objectives. In reality, however, such an assumption is untenable. The world has learned that information, intentions, and everything else about Russian president Vladimir Putin’s statements and actions are opaque.

The perversion in the logic of mutually assured destruction is that the goal of conflict is out of proportion to the means to achieve it. In the logic of mutually assured destruction, each country’s goal is ‘survival in the world’ and each country treats ‘the world’ ’as a means (i.e. hostage) to that end. But the balance between the goal (survival of individual nations in the world) and the means used to achieve it (destruction of the world) is not proportionate.

It is like saying that a gang that controls Tokyo and a gang that controls Osaka are fighting to expand their power, and if the Osaka gang is about to lose, they will kill all 20 million Tokyo residents. Such a threat, if carried out, would make any goal (in this case, expansion of the gangs’ power) meaningless.

In the first place, there is no legitimacy in a game in which the parties to the conflict have the (largely undisputed) authority to determine the existence of the entire world. It is just as unjustifiable to assume that gangs have the right to kill or not kill entire populations of cities.

It is necessary to resolve such vulnerabilities and perversions and consider stable nuclear deterrence. To overcome the vulnerabilities, the nuclear powers must be stopped from ascending the ladder of nuclear escalation because ascending that ladder will increase tensions and the likelihood of unforeseen events.

To overcome the perversion, we also need to define a game that includes as players the entire world (the rest of the world) outside the parties to the conflict, who are unrelated to the conflict but would suffer tremendous damage from the use of nuclear weapons.

The victims of nuclear warfare from the rest of the world are not merely those who are currently living in non-party countries. All future generations are victims in that a countless number of generations may cease to exist – not only humans but every living thing on earth. Whatever the reason, purpose, or cause for the conflict between the two parties, it cannot justify endangering the future of all living things on our planet.

In 2,000 years, the current invasion of Ukraine will seem a pointless conflict, not worth risking the survival of humanity – just as the reasons for the Punic Wars 2,000 years ago do not matter to us today. For the entire world, therefore, the main goal is to prevent the conflicting parties from climbing the ladder of nuclear escalation.

As a mechanism to prevent any party from ascending the first step of a nuclear ladder, we may consider creating a treaty that imposed sanctions for the pre-emptive use of nuclear weapons. Such a treaty would ‘impose immediate, unconditional, and maximum sanctions against any nation that launched a nuclear pre-emptive strike’. All non-military sanctions could be used, including economic sanctions and also other enforcement measures, such as exclusion from international frameworks.

This is tantamount to establishing a new norm that ‘a nuclear pre-emptive strike, even a limited one, is a criminal act against humanity in that it endangers the survival of all human beings unrelated to the conflict in question.’

Note that the rejection of the pre-emptive use of nuclear weapons is incompatible with the current Japanese government’s thinking. Although it is unlikely that the Japanese government will make such a proposal under the current circumstances, it is still meaningful to start from a blank slate to discuss new norms for nuclear deterrence, including theoretical possibilities, in response to the tail risk of nuclear use.

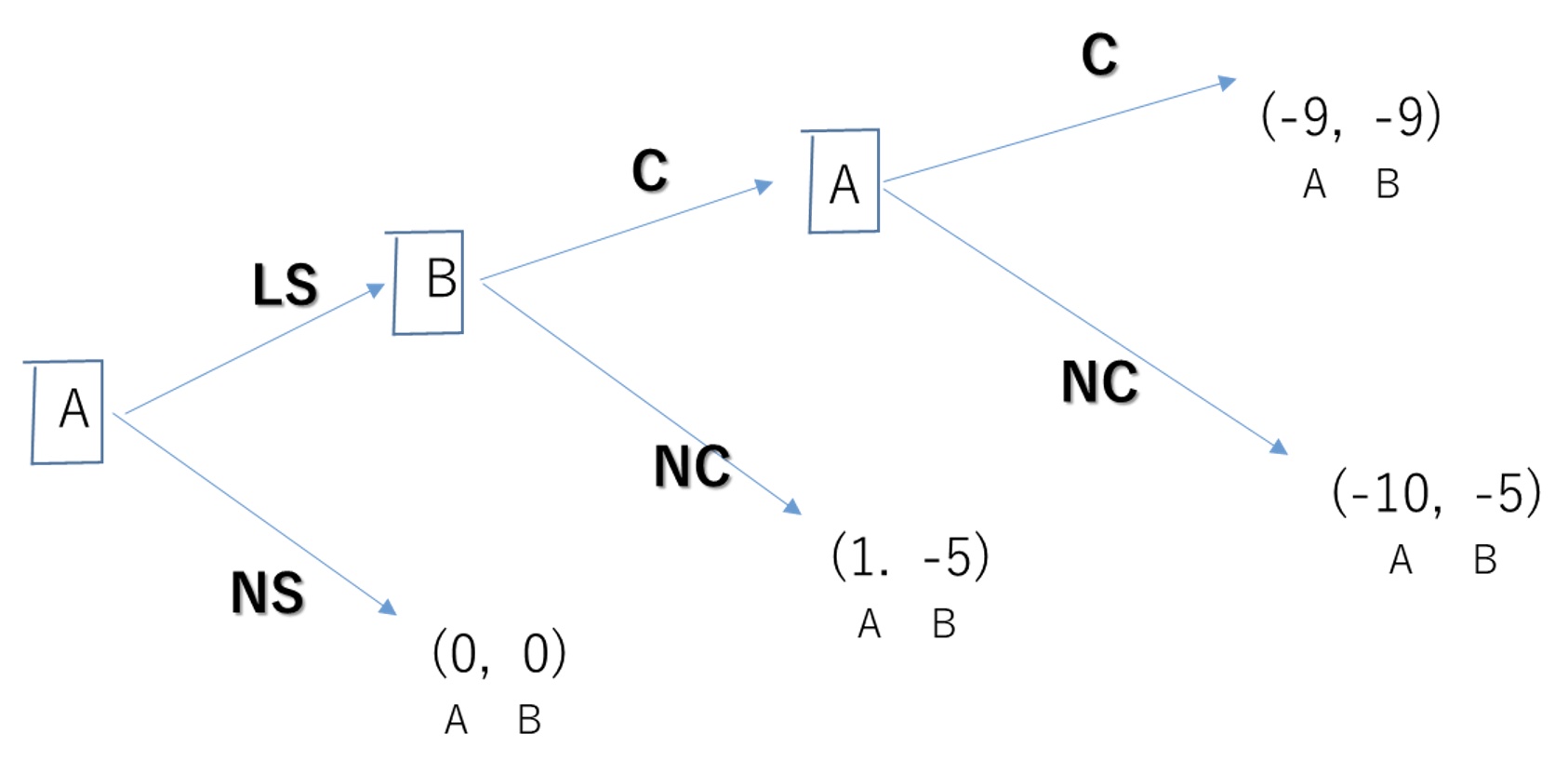

Let’s consider the effectiveness of the new treaty in a diagram. Figure 1 shows the usual two-party game of nuclear deterrence. In a conflict between nuclear powers A and B, A decides whether to launch a strike with limited use of nuclear weapons (LS) or not to strike (NS), then B decides whether to counterattack (C) or not (NC), and then A decides whether to counterattack (C) or not (NC). If both countries choose C, all-out nuclear war will result.

Figure 1 Bilateral games over the deterrence of the use of nuclear weapons

Note: This is the extensive form of a three-stage sequential game, in which State A moves first, State B moves second, and then State A moves again.

If both countries are rational, in equilibrium, state A implements limited nuclear use (LS), but state B does not counterattack (NC), and nuclear escalation does not occur. In theory, all-out nuclear war is avoided. In the real world, however, once nuclear weapons are used, even on a limited scale, uncertainties spread, and the possibility of an all-out nuclear war is no longer zero.

Figure 2 shows what would happen if all countries in the world joined a treaty that imposed sanctions for the pre-emptive use of nuclear weapons. In this case, the gain that would result from a pre-emptive nuclear attack by state A would be negative because sanctions would be imposed by the rest of the world for its limited use of nuclear weapons. In Figure 1, without sanctions, it would be impossible to stop the limited use of nuclear weapons by state A. However, as shown in Figure 2, if it is known in advance that countries around the world will impose sanctions on a nuclear-using state, state A will not use nuclear weapons first because there are no gains to be had from limited nuclear use in the first place. Thus, the first step in nuclear escalation is prevented. Since nuclear use will not occur in the equilibrium, sanctions will not be necessary, and as a result, the sanctioning countries will not incur any costs.

Figure 2 If many countries participate in a sanction on the pre-emptive use of nuclear weapons

Note: (X, Y) is the gain of (State A, State B)

Although the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons entered into force in 2021, the abolition of nuclear weapons is currently unrealistic because it cannot be achieved without the consent of all states possessing nuclear weapons. The Treaty does not provide for sanctions against the use of nuclear weapons. If a treaty on sanctions to the pre-emptive use of nuclear weapons can be created, sanctions can be implemented even if the signatories are non-nuclear-weapon states. Thus, this treaty would create a new international norm with high credibility. Establishing such a treaty is tantamount to the creation of an international norm of equity in which all citizens of the world equally share the power to decide the fate of this planet.

Author’s note: This column was reproduced with permission from the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI). The original article appeared in Nikkei Shimbun on 15 June 2022 and was translated by RIETI with some additional information.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment