Is austerity a ‘dream come true’ for neoliberals, or did the global financial crisis force policymakers to question neoliberalism’s core principles and change direction? Focusing on speeches by members of the International Monetary Fund, Kevin Farnsworth and Zoë Irving find little to suggest that the fundamental assumptions of neoliberalism have been displaced.

Kevin Farnsworth is Reader in international and comparative social policy at the University of York.

Zoë Irving is Senior Lecturer in International and Comparative Social Policy at the University of York.

Cross posted from the LSE Blog

It is now over ten years since the collapse of Lehman Brothers paved the way for the biggest, most global, and most significant financial crisis in living memory. It brought the global capitalist economy to its knees, it shook belief and faith in the capitalist system itself, and raised serious doubts about neoliberalism.

The hope that the crisis would give rise to a more progressive capitalism, however, proved to be premature. From the competing visions of recovery, the ascendance of austerity as both a political and an economic project paved the way for the construction of a new economically-elite-driven, capital-centric, shrunken welfare state model founded on a non-ideological, pragmatic, economic ‘truth’.

Contemporary welfare states now exist within a world in which austerity as a broad set of ideas, encompasses the liberal (in a Hayekian sense) desire to shrink the (social welfare) state, deregulate labour and promote private markets as the driver of growth. This has forced a reconfiguration of the fortunes of the wealthy, the interests of capital, the position of middle-income and poorer citizens, and the state itself. And the biggest losers have been the poorest citizens. Nor is this new politics driven simply by economic austerity. An austere politics has sapped the political imagination and robbed people of hope that things might, one day, get better. At every level austerity restricts the terms of debate.

Whilst the Left rail against the cruelty of austerity, for many on the Right the crisis and the ascendance of austerity politics represents a ‘dream come true’. Or does it? Whilst the critical voices are often quiet, there remains a powerful counter-narrative which suggests that in exposing the limitations of neoliberalism, the global crisis and subsequent austerity created a backlash against globalisation and brought the wider costs of unfettered capitalism into public focus. Nationalism, protectionism, and trade wars are widely reported and international organisations are taking a more obvious interest in inequality. More solid emerging evidence of a possible paradigmatic shift came most recently from none other than the IMF, perhaps the archetypal and unapologetic neoliberal institution, and one with the power to shape and frame the relationship between economies and welfare states.

For welfare state progressives, the possibility that austerity’s social harms are gaining purchase in international and public discourse is heartening. However, as our research shows, there is little to feel optimistic about as far as the expansion of social policy is concerned. The post-crisis welfare terrain can be characterised as one of ‘neo-austerity’ – an emboldened set of claims for the residualisation of state welfare combined with spending to safeguard the power of economic elites. This contrasts with post-war ‘socialised austerity’, the ‘permanent austerity’ of the 1990s and the simple austerity of public expenditure cuts.

Neo-austerity implies not less, but more reliance on the state to enforce, support and compensate for social, political and economic losses. But while a range of discretionary social provisions and services, from public spaces to social care, are erased from the social citizenship balance sheet, demand is increased for state support for private business and pressures for ‘social’ investment. This is the key policy problematic that governments and international organisations are currently grappling with – this rather than the morality of inequality is the major contradiction within neoliberalism. The rise of the nationalist Right is, in many ways a response to this counter-narrative. It has sought to capitalise on the discontent by promising a cure for the symptoms of austerity. But of course, nationalist politics do little or nothing to change the medicine!

The public statements of the IMF are an important discursive window through which to examine the strength of austerity in maintaining neoliberalism. Rather than coding the content of speeches ourselves, our approach let maths categorise the data. Our research utilised quantitative textual analysis (exploiting the capabilities of WordStat) to examine all public speeches by senior IMF representatives between 2004 and 2015.

The contradictions are clear but there is little to indicate that conviction in the economic fundamentals are on the wane. The IMF has at times appeared ‘off-message’ in its advice during the period of the Great Recession, but economic growth through private market development has remained its key priority. Unlike national governments, the IMF is an organisation playing the long and global game.

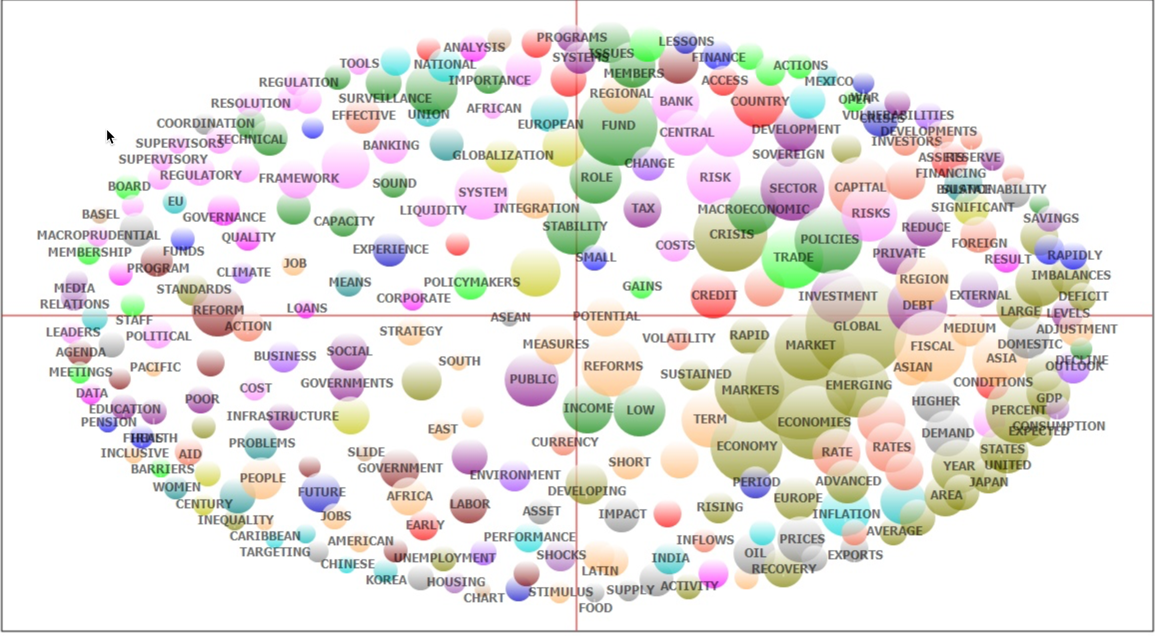

Figure 1: the most frequent and important keywords in IMF speeches, 2004-2015.

Figure 1 is a ‘concept bubble map’, a visualisation of the most frequent and important keywords in the full population of 597 speeches. The size of the bubble represents the frequency of the concept as it appears in the speeches (as a percentage of all words within a given speech), with keywords most commonly found within the same sentences located closest together.

The largest bubbles are related to the economy, markets, finance and trade and appear as a coherent pattern. It is no surprise that the IMF’s core concerns are economic, but what is important for social policy is just how peripheral and how fragmented social concepts (pensions, health, education, benefits, people and so on) really are. The picture is a discomforting reminder that the ‘socialisation of global politics’ is a long way from becoming a reality.

Using the software to identify keyword clusters, word usage and associations of keywords with other keywords reveals incremental patterns over time: words linked to social policy (education, social protection, poverty) feature more heavily after 2009 than before (particularly in the speeches of Christine Lagarde). Conversely, words most closely linked to ‘rolling back the state’ appear more regularly pre-crisis. Notably the word ‘inequality’ becomes a keyword in 2014.

Looking at the individual words in the context of the full speeches, also confirms a greater level of concern regarding income and gender inequality, poverty, and unemployment over time. Running through this discourse however, is a familiar argument that prioritises the economic above the social: cuts in social expenditure are regarded as problematic, where they risk undermining growth, and greater economic equality is important because it promotes growth.

Our research suggests that although the IMF is some way from pure Hayekian libertarianism, it remains a strategic interventionist. There is acceptance that some modicum of state social provision may be necessary to keep the political peace and enable markets to freely operate. This should not be conflated with an indication that the position the IMF now advocates is any less ‘neoliberal’ or ‘austerian’ than before however.

Social welfare in the face of neo-austerity is in fact more, not less fragile for two key reasons. Firstly, even as the costs of austerity are conceded, once growth is restored so the economic ‘need’ for social policy may take a backward turn. Secondly, the reframing of social spending from a direct commitment to citizens to an indirect benefit gained through investment in purported wealth creators dissolves the bonds that social contracts seek to create. Such trends are simply pushing social welfare states towards corporate welfare states.

Judging by the statements of the IMF, the contemporary iteration of neoliberalism promises its proponents a more market-friendly social settlement, and for its opponents more of the same. There is a growing sense that neo-austerity is not working for capital, let alone for citizens so there is always the possibility that neo-austerity will eventually eat itself. Should we therefore take comfort that we’re past peak austerity? The language has changed but practice hasn’t: so no, we’re not even close.

Be the first to comment