The widespread notion that there is simply not enough houses being built is ignorant of the facts. You can’t tackle the housing crisis without tackling the liberalisation of the housing market.

Cross-posted from Positive Money

Debates about house prices still circulate around house building – or lack thereof. Last year, the government remained behind on its ‘300,000 homes a year’ goal. Liz Truss’ plans to scrap “Stalinist”housing targets proved one of the few that stuck. Campaigners around the UK continued to battle with developers and councils to save their own homes from demolition. Discussions among politicians and within the media throughout 2022 exemplified that the housing crisis is still primarily portrayed as a problem of more people than homes.

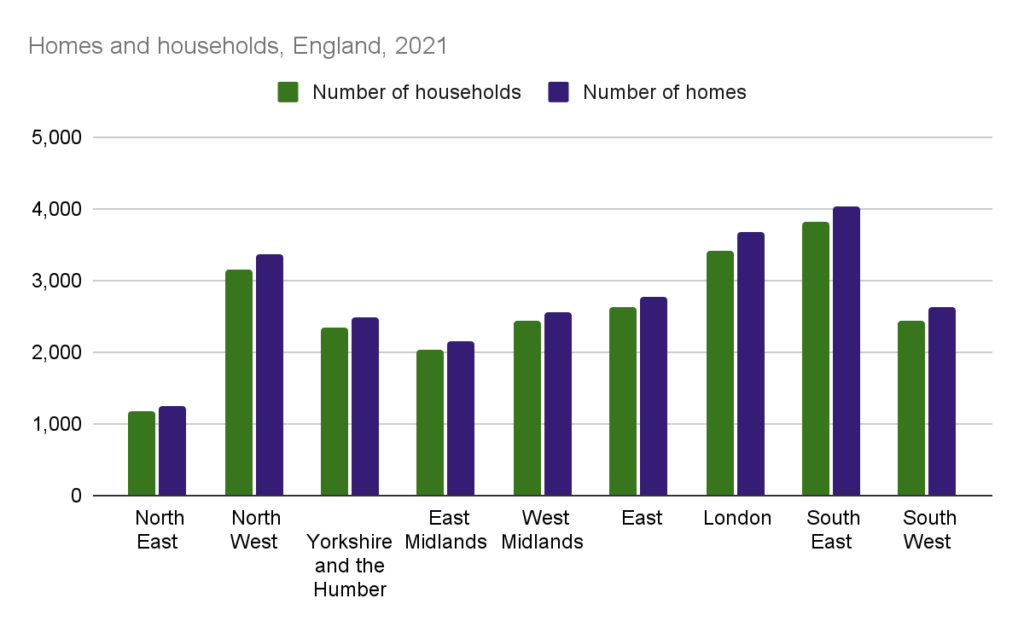

However, census data released last week reveals that in 2021 there were 1.4 million more dwellings than households in England. That’s 6.1% more places to live than households to fill them. This was the case in all regions, with the greatest proportional ‘excess in dwellings’ occurring in the South West (7.3%), London (7.2%) and the North East (6.7%). In London, amid a population dip during the so-called ‘race for space’, this amounted to 250,000 more homes than households.

Source: Office of National Statistics (ONS), 2023 and MHCLG, 2022.

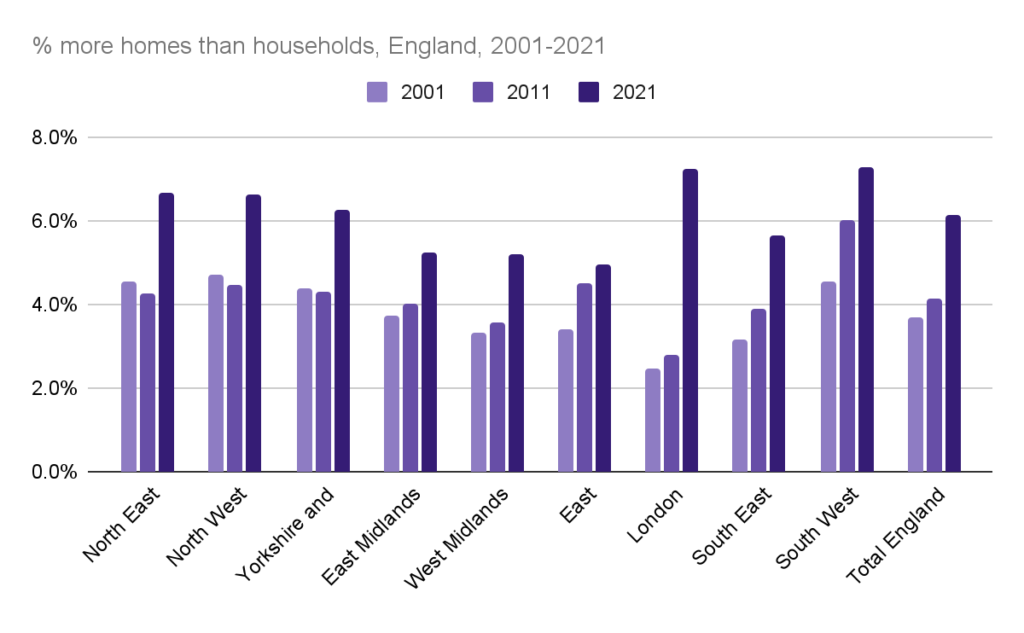

But this was not a pandemic blip. In both 2001 and 2011, the census recorded a greater number of homes than households in England. In fact, the surplus has increased: in 2001, there were just 757,000 more dwellings than households, nearly half the 1.4 million in 2021. In the last 20 years there has been no region of England where there was a net shortage in dwellings, and every region has seen its surplus building stock grow since 2001. There are, of course, local areas that face increased demand, and the chronic depletion of social housing options within the overall building stock is well documented. But it appears that, if well managed, there should be more than enough physical infrastructure to go around.

Source: ONS, 2023 and MHCLG, 2022.

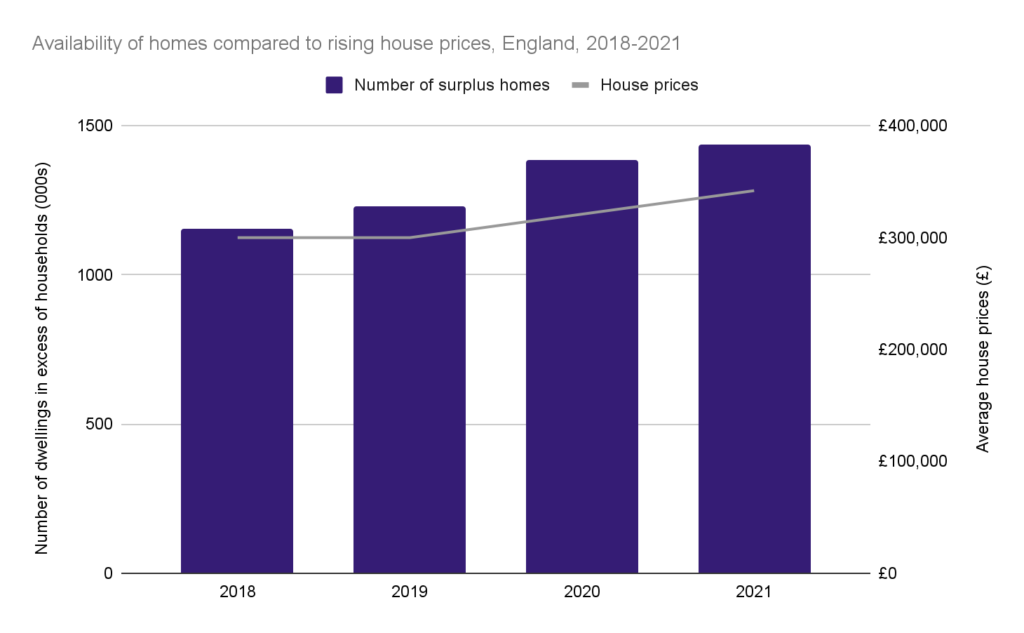

This confounds the prevailing narrative that the housing crisis is primarily a shortage of supply. It also suggests that building more homes will not ease the drastic increases in house prices we’ve seen in the last decades. Between 2018-2021, the surplus of English homes grew from 1.2 million to 1.4 million. Despite this increase in supply, average house prices rose by 14% in that same period. Indeed, the government’s own house price model suggests that even if the housebuilding target hated by Truss had been met — 300,000 a year since 1996 — the average house today would only be 7% cheaper, doing little to counteract the 120% increase in real house prices over the past 30 years.

Source: ONS, 2022; ONS, 2023.

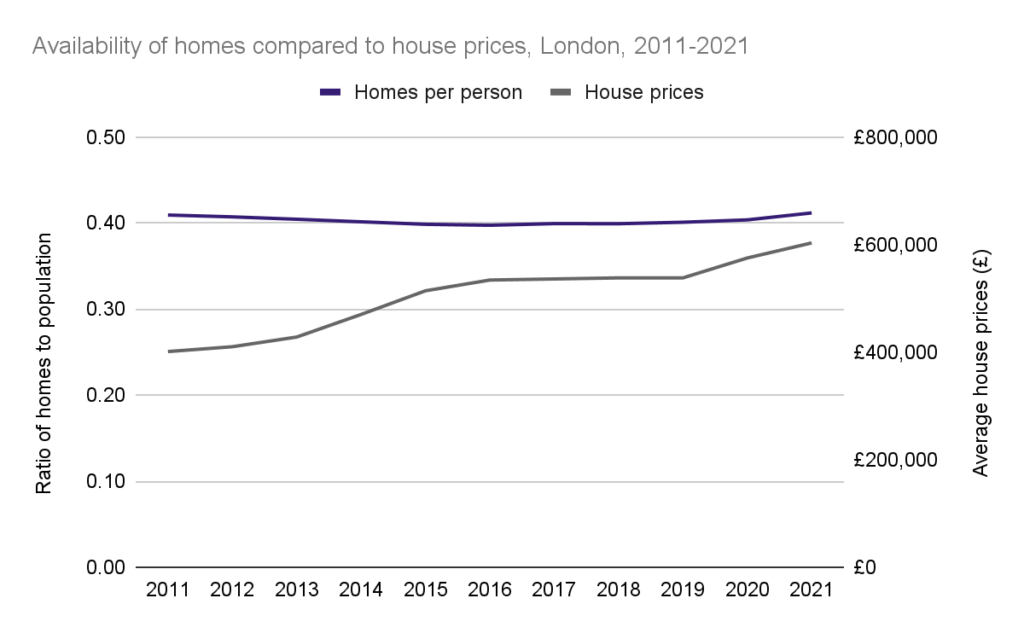

The notoriously unaffordable London market is a stark illustration of this point. Between the two census releases, the GLA estimates that London’s population increased by about 9%, falling slightly during the pandemic. In the same period, government data indicates that the number of dwellings in London increased in the same proportion – meaning that there was a roughly stable ratio of homes and people in the capital for the last decade. Between 56,000 to 88,000 of these homes were officially recorded as vacant, and there was an estimated 20 million square feet of empty office space — some of which local authorities are beginning to try to convert into homes — before the pandemic even began. And yet, average house prices in the capital rose 50%, from £401,000 to over £600,000. Today, as house prices appear to be falling, once again there is no discernible change in supply that is driving that change. As in the rest of the UK, London suffers from a lack of affordable and social building stock, horrific inequality in home quality and affordability (particularly for Black, Brown and working class households) and a downward spiral of conditions in the private rented sector. But a lack of building stock is not the sole or even primary driver for these problems.

Source: Greater London Authority (GLA), 2021; ONS, 2022 and MHCLG, 2022.

Despite its relatively low impact on house prices, debates about housing supply threaten to mask more significant, and perhaps more insidious, drivers of the housing crisis. Positive Money’s research has indicated that a campaign of financial liberalisation, mortgage reform and lack of investment in the existing building stock has transformed English homes into crumbling vehicles for the accumulation of wealth. Home ownership has increasingly become the preserve of the wealthy, with billions pumped into property purchases by overseas investors, landlords and retail banks. Outdated tax and land sale systems locktenants into escalating fees and bizarre overpayments, with insufficient options to secure rights and controls over their tenancy. The massive sell off of social housing, conducted without proportionate legal frameworks for councils to buy homes back or communities to create new, cooperative forms of home ownership, is forcing people into a choice between precarious and expensive mortgages, or precarious and expensive private rents.

As we enter 2023, the UK faces a downturn in house prices, an energy crisis that has thrown 1 million into fuel poverty, and renewed calls for a ‘war effort’ to retrofit, repair and decarbonise our homes. This escalation of the housing crisis is a direct result of decades of policies that have made our homes expensive, neglected and precarious. We do need more affordable housing – but we also need to rethink the finances of the whole system.

You decide if we close down BRAVE NEW EUROPE and the Gig Economy Project

At the end of 2022 thanks to many of you we had raised round 13,000 GBP/€/ for 2023.With 14,000 we can continue, although in a reduced format of five days a week. Thus we are asking those of you who have not donated yet to do so. If we made it this far, we should manage the last mile.

Be the first to comment