The university strike in UK is growing in strength and public support. In his second report (read the first here) Michael Mair brings us up to date as well as analysing the importance of this strike in relation to the development of employment practices in Britain.

Dr Michael Mair is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Liverpool and works on politics, accountability and contemporary warfare and conflict.

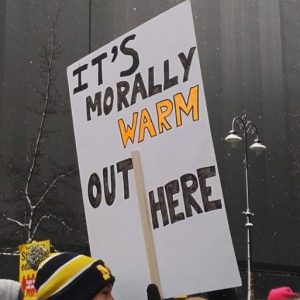

As it enters its second phase, the scale and impact of the UK’s university strike, and the resolve shown by striking university staff, continues to take everyone by surprise. Despite facing the coldest late February/early March weather in the UK in 30 years, support for the strike has been growing, with more and more people joining the University and College Union (UCU) and taking to the picket lines every day the industrial action continues. On the other side, the employers’ body, Universities UK (UUK), is increasingly beleaguered – not just by university staff and their representatives but by the pillars of the establishment right, the Times, the Daily Telegraph, even the Daily Mail, and the Conservative Party, with documentaries and newspaper front pages daily pouring scorn on their position and excesses. Consistently strong support among students for the strike has put further pressure on university management to back down. Sensing defeat, many within UUK have publicly broken rank, with a number of principals and vice-chancellors around the UK voicing their support for those on strike, one doing so from the picket line.

Taking the 14 days as a whole, the university strike represents one of the longest periods of industrial action undertaken in the UK since the government passed the highly restrictive Trades Union Act in 2016, a legal framework which required 50% turnout in every individual workplace being balloted for industrial action to go ahead. It is clear UUK felt university staff were not capable of meeting that threshold and, even if they did, that they would not call for or be capable of sustaining an extended period of strike action based upon an authorising vote. That the UCU received such a strong mandate, with 58% turnout and 88% support for industrial action, and then called for 14 days of strikes, the longest period of strike action ever seen in UK higher education, completely wrong-footed UUK. Given that university staff could go on strike from anywhere between 11 and 15 years, as was pointed out last week, and still lose less financially than under the UUK proposals, this should not have come as the surprise it did. That strategic miscalculation is already having repercussions that go beyond the current dispute.

Although the industrial action was triggered by the aggressive changes to pensions proposed by UUK, it is also a challenge to the emergence of a market-driven, financialised, corporate model of the university in the UK from the late 1990s on – the model which acted as the incubator for the current pension proposals. Insofar as universities have become microcosms of the wider British economy, with growing casualisation and employment insecurity going hand-in-hand with the steady erosion of employment rights and management systems geared to surveillance and the production of bad jobs, the strikes represent a rejection of the economic status quo that has come to characterise work in Britain following the financial crisis. University staff, like workers across the UK, have had enough and the pension proposals proved a tipping point. The dispute thus raises a whole series of issues about the way in which employees are dealt with by their employers in Britain today, and, having brought those issues into the public domain, UUK are coming out of this dispute very badly indeed.

In choosing to sacrifice the pensions of university staff for the pursuit of higher profits, investment portfolios and budget surpluses, UUK has made British universities’ priorities clear for all to see. That has had a galvanising effect. First, students saw that the attitude British universities have displayed towards their staff in this dispute is the same attitude they have towards them. As a consequence, support among students has been incredible from the start, with large numbers of students joining staff the picket lines every day, organising fund-raisers and staging occupations of university buildings. They realise the future of higher education is at stake and are making common cause with UCU. Second, with the university pension scheme one of the smallest of the remaining large-scale guaranteed occupational pension schemes in Britain, workers in other areas have quickly realised this is a test case: if the moves against university staff are to succeed, it will be everyone else next, a precedent will have been established. Solidarity from across the trade union movement has thus also been swift, impressive and sustained. Third, in bringing staff, students and workers’ representatives together, politicians have followed public opinion and have also turned against UUK, voicing their anger at the proposals too. With the political mood music in Britain turning from austerity to the challenges of a post-EU referendum world, flagrant corporate irresponsibility under the guise of public service looks like a throwback to the Cameron/Osborne and Blair/Brown years. UUK’s reckless brinkmanship and condescending dismissal of staff, students and their representatives alike has thus managed to unite a broad coalition against it – no mean feat and an indication of the scale of their misjudgement.

It seems increasingly likely, given this, that UUK will have to make concessions. However, they will also seek to give away as little as possible and will try to punish staff for forcing them to do so.

The process has already begun. Last week the strike ran from Monday to Wednesday. On days they are not on strike, university staff are working to contract and employers have tried to fine them 100% of their wages for doing so, treating working to contract as equivalent to being out on strike. Staff at Sheffield University, among others, employed social media as part of an organised response to this threat and the backlash, particularly from alumni who threatened to withdraw their financial donations to the university, forced a retreat. Other institutions have subsequently climbed down too. While that particular tactic looks to have failed, however, others are being tried out instead. Several universities are instead demanding staff provide replacement materials for students and reschedule classes cancelled as a result of the strikes. That is, if university staff do not make up for work missed due to the strike, 100% of their wages will be docked until they do. This amounts to demanding that individuals undermine their own industrial action and, as a result, staff at those institutions have refused to do so. This will likely mean, however, an open-ended extension of a dispute UUK has brought upon itself. Many universities have also suggested refusal equates to a breach of contract and have threatened to deal with staff on that basis, raising the spectre of disciplinary proceedings and, potentially, sackings. So much for institutions who regularly publicly proclaim their commitment to the staff who keep them running. Instead of seeking to work with their staff to ensure the dispute is resolved in a way that addresses real concerns about the contemporary university, they are drawing on some of the most draconian anti-trade union legislation in place in Europe in an attempt to strip their employees of the very right to withdraw their labour in the first place and erase the strike after-the-fact.

Although we will continue to see the deployment of such tactics, university staff remain committed to the action they have taken. It is precisely because such tactics are now being deployed that taking action is so important. The stance of universities is not just vindictive and bullying, therefore, it is also counter-productive because it hardens resolve against them. Indeed, one reason the strike has been so well supported and will be successful is that everyone understands the issues are serious and thus demanded a serious response. Again, few can think institutions which have opted to do this care much about their staff. Our employers have made it very clear what they think of us, and that has been salutary, the scales have fallen from our eyes.

While it is too early to predict what will happen, it is appropriate to give some thought to what comes next given we do now know where we stand. The social, political and economic landscape in Britain is shifting and the processes put in motion by the dispute will not end when it does. Strikes, as a number of commentators have noted in their discussion of this action, change things. They establish new lines of solidarity, they are instructive and they are educative. We come to know the worlds we live and work in differently as a result of participating in them. No matter how we choose to frame such matters, however, the question of what happens now is clear to many. There is widespread consensus, for instance, that British universities have to change and the current strike will be one catalyst for that change. But this is not just about universities: universities reflect the contemporary British workplace all too well and change is coming there too. University staff, in taking this action in defence of their pension rights, are thus contributing to something broader. As this action gains momentum and spreads, that is something UUK as well as other employers would do well to reflect upon. Things will not stop here. By virtue of the action they have taken, those on strike are already reconfiguring the social, political and economic relations of the university as a contemporary workplace and that could prove a dangerous example indeed.

Be the first to comment