Michael Roberts takes another look at the development of the world economy.

Michael Roberts – Economist in the City of London and prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts Blog

The IMF-World Bank meeting in Washington this weekend revealed again that the world economy is slowing down and the prospect of an outright recession is getting much higher. The IMF economists cut their outlook for global growth to the lowest since the global financial crisis of 2009 amid a bleaker outlook in most major advanced economies and signs that higher tariffs are weighing on trade – “a growth slowdown and precarious recovery”, the IMF called it.

The IMF estimates that the world economy will grow 3.3% this year, down from the 3.5% it had forecast for 2019 in January. It’s the third time the IMF has downgraded its outlook in six months. The new IMF chief economist, Gita Gopinath reckoned the global economy had entered “a delicate moment”. She offered a decisive insight: “If the downside risks do not materialize and the policy support put in place is effective, global growth should rebound. If, however, any of the major risks materialize, then the expected recoveries in stressed economies, export-dependent economies, and highly-indebted economies may be derailed.” So, on the one hand or on the other….

Alongside the IMF view, the private Brookings Institution delivered its view on the global economy, concluding from its tracking index of economic activity that the world had entered a “synchronised slowdown” which may be difficult to reverse. The Brookings-FT Tracking Index for the Global Economic Recovery (Tiger) compares indicators of real activity, financial markets and investor confidence with their historical averages for the global economy and for individual countries. The headline readings slipped back significantly at the end of last year and are at their lowest levels for both advanced and emerging economies since 2016, the year of the weakest global economic performance since the financial crisis.

Brookings did not reckon a recession was imminent but “all parts of the world economy were losing momentum.” Even if a global recession is not yet with us, it is clear from the latest data on the major economies that the long depression, as I have characterised this period since 2009, is still with us. Frances Coppola, the heterodox economist, has also blogged that capitalism is locked into a long depression and makes similar points to me on its outcome. But as for causes, Coppola, like other Keynesians, holds to the idea of ‘secular stagnation’, namely that the depression is due to a chronic “lack of demand’’. Regular readers of this blog know that I do not consider this is an adequate explanation of crises and depressions. In a profit-making economy, it is the profitability of capital that matters.

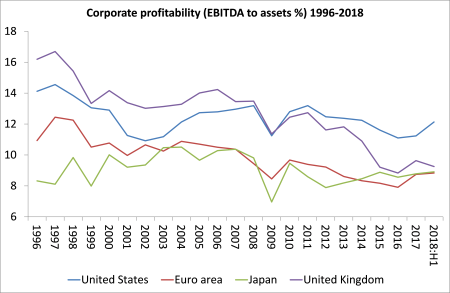

And here, the IMF’s new Global Stability Report offers more support for my causal interpretation of the long depression. Confirming what I have shown empirically before, the IMF finds that corporate profitability (as measured by corporate earnings as a share of the stock of assets) in the major economies has not recovered to 2008 levels. Indeed, profitability of capital is well below levels of the late 1990s.

This long depression has similar characteristics as the late 19th century depression and the Great Depression of the 1930s. The first was resolved by a series of slumps eventually driving up profitability and second was resolved by a world war. It’s my view that this one will be resolved more like the 19th century one.

Low profitability explains above all else why corporate investment has been so weak since 2009. What profits have been made have been switched into financial speculations: mergers and acquisitions, share buybacks and dividend payouts. Also there has been hoarding of cash. All this is because the profitability of productive investment remains historically low.

As Gillian Tett in the FT put it: “the IMF calculates that American companies made shareholder payouts and buybacks that were worth 0.9 per cent of assets last year, twice the level seen in 2010. Little wonder that equity markets have soared (leaving aside the wobble late last year). Companies have also used this arsenal for a mergers and acquisitions boom: such deals gobbled up cash flows equivalent to 0.4 per cent of assets in 2019, compared with virtually nothing in 2011. But the amount of cash flow spent on capex, in contrast, has flatlined since 2012, running at around 0.7 per cent of all assets — smaller than the cash flow spend on shareholder payouts. Or, as the IMF report notes: “Strong profits in the United States were used for payouts and other financial risk taking.” But not, it seems, lots more investment.

The other key factor in the long depression has been the rise in debt, particularly corporate debt. With profitability low, companies have run up more debt in order to fund projects or speculate. The big companies like Apple or Microsoft can do this because they have cash hoards to fall back on if anything goes wrong; the smaller companies can only manage this debt spiral because interest rates remain at all-time lows and so servicing the debt is still feasible – as long as there is not a downturn in sales and profits.

Again the IMF’s Global Stability Report sums up the issue. “In most advanced economies, debt-service capacity in the corporate sector improved during the recent cyclical upswing. Balance sheets appear strong enough to sustain a moderate economic slowdown or a gradual tightening of financial conditions. However, overall debt levels and financial risk taking have increased, and creditworthiness of borrowers has deteriorated in the investment-grade bond and leveraged loan markets. A significant downturn or a sharp tightening of financial conditions could lead to a notable repricing of credit risks and strain the debt-service capacity of indebted firms. Should monetary and financial conditions remain easy for longer, debt will likely continue to rise over the medium term in the absence of policy action, raising the risk of a sharper adjustment in the future”.

Each crisis has a different trigger or proximate cause. The 1974-5 international recession was triggered by a sharp rise in oil prices and the US coming of the dollar-gold standard. The 1980-82 slump was triggered by a housing bubble in Europe and a manufacturing crisis in major economies. The 1990-2 recession was triggered by the Iraq war and oil prices. The 2001 mild recession was the result of the bursting of the dot.com bubble. And the Great Recession was started with the collapse of the housing bubble in the US and ensuing credit crunch brought on by the international diversification of credit derivatives. But underlying each of these crises was the downward movement in the profitability of productive capital and eventually a slowdown or decline in the mass of profits. (The profit investment nexus).

This time I reckon the trigger will be in corporate debt as companies get overstretched on cheap credit and as profits fall and interest costs rise, they become insolvent. Marxist economist Eric Toussaint of the CADTM, agrees. “This mountain of corporate private debt will be a prime element in the next financial crisis.” He points out that “As interest rates climb the value of corporative debt sinks. The greater the share of sinking corporate debt in a company’s assets, the greater the negative impact on the corporate balance sheet. The corporate equity value sinks too and may get to a point where it no longer covers its obligations. In 2016 Apple informed US authorities that in the case of a 1% increase in interest rates it would lose $4,.9 billion. Of course, just like other companies Apple borrowed to finance its debt purchases. In 2017 Apple has already borrowed $28 billion, bringing the total to $75 billion. This, by domino effect, could produce a crisis of similar ampler to that of the US financial crisis in 2007-2008.”

As the IMF chief economist puts it: capitalism is in a delicate moment.

Be the first to comment