The result of automation in the last 30 years has been rising inequality of incomes.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’s blog

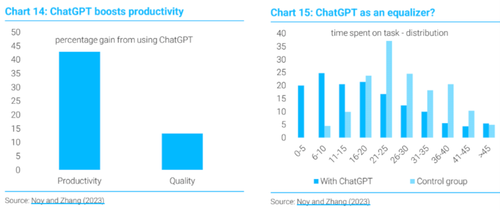

There is a new burst of techno-optimism emerging over the application of ChatGPT and LLMs. One analyst reckons that AI “has huge potential to boost economy-wide productivity” and cited a recent MIT study that showed a massive improvement in productivity while using ChatGPT. Also, much of the productivity gains were seen between 21 to 40-year-olds.

ChatGPT has gained 100 million users faster than any other application in history and these fast adoption rates are not confined to individual users. Major corporations, such as Bain & Company, have entered into deals with OpenAI to use generative AI in their strategy consulting business, while companies like Expedia have integrated ChatGPT through plug-ins.

So is ChatGPT etc a game changer for capitalism? MIT economics professor Daron Acemoglu is the expert on the economic and social effects of new technology, including the fast-burgeoning artificial intelligence (AI). He’s won the John Bates Clark Medal, often a precursor to the Nobel Prize.

But he is no techno-optimist. His research shows that major technological disruption — such as the Industrial Revolution — can flatten wages for an entire class of working people. In a recent interview in the Financial Times, Acemoglu said “capital takes what it will in the absence of constraints and technology is a tool that can be used for good or for ill.” Referring to the technology in the 19th century onwards, he went on: “Yes, you got progress, but you also had costs that were huge and very long-lasting. A hundred years of much harsher conditions for working people, lower real wages, much worse health and living conditions, less autonomy, greater hierarchy. And the reason that we came out of it wasn’t some law of economics, but rather a grass roots social struggle in which unions, more progressive politics and, ultimately, better institutions played a key role — and a redirection of technological change away from pure automation also contributed importantly.”

These comments echo the conclusions on the impact of technology that Friedrich Engels made during the height of industrial revolution in the mid-19th century. Back then, Engels argued that mechanisation shed jobs, but it also created new jobs in new sectors, see my book on Engels’ economics pp54-57. Marx also identified this in the 1850s: “The real facts, which are travestied by the optimism of the economists, are these: the workers, when driven out of the workshop by the machinery, are thrown onto the labour-market. Their presence in the labour-market increases the number of labour-powers which are at the disposal of capitalist exploitation…the effect of machinery, which has been represented as a compensation for the working class, is, on the contrary, a most frightful scourge. …. As soon as machinery has set free a part of the workers employed in a given branch of industry, the reserve men are also diverted into new channels of employment and become absorbed in other branches; meanwhile the original victims, during the period of transition, for the most part starve and perish.” (Grundrisse). The implication here is that automation means increased precarious jobs and rising inequality for long periods.

Acemoglu reaches similar conclusions to Engels and Marx. “I think one of the things you have to do as an economist is to hold two conflicting ideas in your mind at the same time,” he says. “That’s the fact that technology can create growth while also not enriching the masses (at least not for a long time). Technological progress is the most important driver of human flourishing but what we tend to forget is that the process is not automatic.” Under the capitalist mode of production for profit not social need, there is a contradiction, so “mathematically modelling and quantitatively understanding the struggle between capital — which benefits most from technological advancement —and labour isn’t an easy task.” Indeed.

Acemoglu’s own extensive research on inequality and automation shows that more than half of the increase in inequality in the U.S. since 1980 is at least related to automation, largely stemming from downward wage pressure on jobs that might just as easily be done by a robot. The result of automation in the last 30 years has been rising inequality of incomes. There are many factors that have driven up inequality of incomes: privatisation, the collapse of unions, deregulation and the transfer of manufacturing jobs to the global south. But automation is an important one. While trend GDP growth in the major economies has slowed, inequality has risen and many workers — particularly, men without college degrees — have seen their real earnings fall sharply.

Moreover, under capitalism, Acemoglu adds that not all automation technologies actually raise the productivity of labour. That’s because companies mainly introduce automation in areas that may boost profitability, like marketing, accounting or fossil fuel technology, but not raise productivity for the economy as a whole or meet social needs. “Big Tech has a particular approach to business and technology that is centered on the use of algorithms for replacing humans. It is no coincidence that companies such as Google are employing less than one tenth of the number of workers that large businesses, such as General Motors, used to do in the past. This is a consequence of Big Tech’s business model, which is based not on creating jobs but automating them.”

Acemoglu reckons modern automation, particularly since the Great Recession and the COVID slump, is even more deleterious to the future of work. “Put simply, the technological portfolio of the American economy has become much less balanced, and in a way that is highly detrimental to workers and especially low-education workers.” He reckoned that more than half, and perhaps as much as three quarters, of the surge in wage inequality in the US is related to automation. “For example, the direct effects of offshoring account for about 5-7% of changes in wage structure, compared to 50-70% by automation. The evidence does not support the most alarmist views that robots or AI are going to create a completely jobless future, but we should be worried about the ability of the US economy to create jobs, especially good jobs with high pay and career-building opportunities for workers with a high-school degree or less.” His analysis of automation’s effects in the US also applied to the rest of the major capitalist economies.

As Acemoglu once explained to the US Congress: “American and world technology is shaped by the decisions of a handful of very large and very successful tech companies, with tiny workforces and a business model built on automation.” And while government spending on research on AI has declined, AI research has switched to what can increase the profitability of a few multi-nationals, not social needs: “government spending on research has fallen as a fraction of GDP and its composition has shifted towards tax credits and support for corporations. The transformative technologies of the 20th century, such as antibiotics, sensors, modern engines, and the Internet, have the fingerprints of the government all over them. The government funded and purchased these technologies and often set the research agenda. This is much less true today.” That’s the business model for AI under capitalism.

Acemoglu baulks at conventional policy for dealing with tech-based inequality, such as universal basic income, because “it leaves the underlying power distribution the same. It elevates people who are earning and gives others the crumbs. It makes the system more hierarchical in some sense.”

Instead: “I think the skills of a carpenter or a gardener or an electrician or a writer, those are just the greatest achievements of humanity, and I think we should try to elevate those skills and elevate those contributions,” he says. “Technology could do that, but that means to use technology not to replace these people, not to automate those tasks, but to increase their productivity by giving them better tools, better information and better organisation.”

But he has a touching belief in the current US administration. “Biden is the most pro-worker president since Franklin D Roosevelt.” Acemoglu reckons “We need to create an environment in which workers have a voice” — though not necessarily the current union structure.” He looks to the ‘Germanic model’ in which the public and private sectors and labour ‘work together’, rather than the US’s neo-liberal regimen.

But Acemoglu hints at a better alternative: “You read evolutionary psychology or talk to many people who would say they want to be richer than you, more powerful than the other person and so on, and you think that’s the way it is. But then you talk to anthropologists, and they’ll tell you that for much of our humanity we lived in this egalitarian hunter-gatherer manner — so, what’s up with that?” An egalitarian society where automation is used to meet social need requires cooperative, commonly owned automated means of production. Rather than reduce jobs and the livelihoods of humans, AI under common ownership and planning could reduce the hours of human labour for all. That would be the real game changer.

Be the first to comment