The growing signs of stagflation defy mainstream analysis, which is predicated on the idea that employment and inflation are always moving in opposite directions.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

The US economy has a widening gap: between rising inflation on the one side and employment on the other. According to mainstream Keynesian theory, that should not happen. That’s because a weakening labour market should lead to a fall in wage increases and in consumer demand and price inflation will subside. The experience of the 1970s economies disproved that theory supposedly supported by the so-called Phillips curve (ie a trade-off between price rises and unemployment). Inflation erupted while unemployment rocketed. The decade of the 2010s after the Great Recession again disproved the theory, when inflation in the major economies subsided to near zero and unemployment rates were at record lows. In the post-COVID period from 2021 to 2024, inflation rates rose sharply and yet unemployment rates stayed low.

Why was Keynesian theory wrong? It was because Keynesian theory assumes that it is aggregate demand that drives spending and prices. If demand outstrips supply, prices will rise. However, in each of these periods, the 1970s and the 2010s, it was the supply-side that was the driver, not aggregate demand. In the 1970s, economic growth slowed as profitability of capital and investment growth plummeted and then energy supply was restricted by the oil producers and crude oil prices rocketed. In the 2010s, economic growth crawled, inflation rates dropped but unemployment did not tick up. In 2020s, the post-pandemic slump led to a breakdown of global supply chains, an energy price hike and a reduction in skilled labour. It was a supply-side problem.

Monetarist theory was also exposed in these periods. Central banks – especially the Federal Reserve under Ben Bernanke, a disciple of the arch monetarist Milton Friedman, who claimed that inflation was essentially a monetary phenomenon (ie money supply drove prices) – assumed that the answer to the Great Recession of 2008-9 was to cut interest rates and boost to money supply through what was called quantitative easing (QE) ie the Fed ‘prints’ money and buys government and corporate bonds from the banks, which in turn were expected to increase lending (money supply) to companies and households to spend. But that did not happen. The real economy remained in depression and all money injections simply boosted financial asset prices. Stock and bond prices mushroomed. Again, monetarism ignored the real drivers of economic growth, spending and investment: the profitability of capital ie the supply-side.

Back last February, in a post, I suggested that the US economy had a ‘whiff of stagflation’. ‘Stagflation’ is when national output and employment stagnates or rises only very slowly and yet price inflation continues to rise and even accelerate. The US economy has clearly been slowing. Quarterly growth rates have been erratic, mainly because of wild swings in imports, which surged early this year as companies tried to ‘front-run’ Trump’s import tariff increases, and then real GDP growth slowed as tariffs started to affect necessary import components for industry. But the first half of the year shows a clear slowdown under Trump.

Indeed, economic growth dropping towards what some analysts call “stall speed” — “a pace below which the economy slips into recession (an outright fall in GDP). The US economy is not yet in recession because profits are still rising for the US corporate sector and the AI investment boom is still driving key sectors of the economy. But stagflation is now more than just a whiff in the economic air as it was at the beginning of 2025.

Take jobs. Employment growth is slowing fast and unemployment is creeping up.

In August net jobs increased by just 22,000, while June was revised down to a fall of 13,000.

Trumponomics argued that that tariffs would build up manufacturing jobs and federal workforce cuts would free up workers for them. No chance. Manufacturing lost jobs almost as fast as the federal workforce (-12K vs -15K). Job growth is slowing across nearly all sectors.

Job losses are particularly severe for men. Males have lost 56,000 jobs over the past four months. The main reason is that Trump’s attack on immigration has led to a significant fall in the labour force. The ICE is making mass arrests and deportations, but the number of foreign-born workers in the United States was already shrinking after years of rapid growth. Native-born workers have not gained from this – unemployment there is at its highest rate since the end of the pandemic. Increases in both youth and black unemployment (now at 7.5%, the highest since October ‘21) suggest that the crackdown on immigration has not created a more favourable job market for the more vulnerable components of the US labour force.

Trump sacked the head of Bureau of Labor Statistics after the BLS recorded a very weak jobs growth figure. But since then, annual revisions of the jobs figures have reducedemployment growth by 911k in the year to March 2025. Sacking the messenger does not change the message. US jobs growth has slowed to a rate outside of recessionary periods not seen for more than 60 years. Employment growth is slowing, not because of weak demand but because supply growth is drying up as immigration falls, manufacturing stays in recession and the government agencies and workforce are decimated by Trump.

The basic problem is that a lack of demand is not the constraining factor in American manufacturing; it’s the workforce. The number of workers who are able and willing to work on a factory floor is shrinking. Almost 400,000 manufacturing jobs are currently unfilled, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Fewer productive workers mean less growth. And there is nothing the Fed can do about this, either by cutting interest rates or resorting to more monetary injections (quantitative easing). Even if Trump got his way, sacked some Fed board members, then took control the Fed and to make deep reductions in the Fed’s policy interest rate, all that would do is fuel yet further the speculative boom in the stock market, with little effect on the productive sectors of the economy.

The Fed’s current board is reluctant to cut interest rates because it fears inflation would accelerate. Inflation is already on the up. The latest headline consumer price inflation rate accelerated to 2.9% year over year in August 2025, well above the Fed’s target for inflation at 2% a year. The Fed likes to follow what it calls the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) inflation rate. This always handily lower than the average price rise in consumer goods for American households. But even the PCE is staying above the Fed’s target at 2.6% yoy. The core inflation rate (which excludes energy and food prices) is stubbornly stuck at 3.1% yoy.

Again, this rise in inflation is not due to increased demand for goods and services outstripping supply; it is due slowing production and rising costs within production, particularly in services like utilities, healthcare insurance etc.

The Trump officials argue that that tariffs are having no impact on inflation. But if that were true, then it would mean the ‘supply shock’ to prices was happening anyway. It is true that, so far, the impact of the tariff has been limited. That’s because as soon as Trump started his tariff tantrums, US importers rushed to maximise stocks and run ahead of the tariff hikes. That’s why the US imports rocketed in the first half of 2025 and the US trade deficit sharply worsened.

Also, some foreign exporters to the US reduced their prices to absorb the hit to import prices from the tariffs. But tariff hikes will eventually come through to consumer prices. Already, about 22% of tariff costs have been passed onto consumers, according to a Goldman Sachs analysis. GS reckon that will eventually rise to 67%.

Given that the effective tariff on imports is now around 18% (up from about 4% before Trump started) and imports are about 14% of US GDP, then that can only mean an additional rise of about 1.5% pts to the inflation rate over the next 12 months, taking US inflation up to 4.5-5%.

It’s this potential rise in inflation that worries government bond investors in financial markets. They will want higher yields to compensate for the reduction in real returns from higher inflation. So we can expect US long-term government bond yields to rise even if the Federal Reserve cuts short-term rates.

So the forces driving stagflation are getting stronger. However, that does not mean the US economy is imminently heading into an outright slump. A slump is when total output falls (mainstream economists like to call a fall in total output for two consecutive quarters, a ‘technical recession’). The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) tracks recessions and it applies a wide range of indicators to ‘call’ a slump. But the NBER judgement is always retrospective (ie after the slump is over). So far, the NBER has not called a recession. There are other forecasting models that try to track the rate of expansion in the US economy. The Atlanta Fed GDP Now model is popular. It is currently forecasting US real GDP to be rising 3.1% at annualised rate for the third quarter of this year – although note that the consensus of all the leading forecasters is about 1.3%.

The New York Federal Reserve also has a forecasting model. The New York Fed Staff Nowcast for 2025:Q3 is currently 2.1%. Again, this is an annualised rate, which is not the same as the quarterly rate or the year over year rate. But so far, whatever the measure or model, the US economy is still expected to have expanded from June to September this year, if at a slower pace.

I and others have shown that a slump only follows when business investment contracts sharply and business investment only does so if profits start to fall. So far, business investment is still positive at about 4% a year.

However, much of this growth in business investment is concentrated in high-tech AI spending on data centers and other infrastructure for the supposed boom in AI. Since 2019, that sector of business investment is up nearly 50%, while the rest of US corporate investment is down 7%. The impact of hi-tech, AI investment has budged up the growth rate in the productivity of labour slightly, but it is still below the rate of 1990s and 2000s. If the AI investment boom falters, then business investment will plummet.

As for profits, US business has done much better than anywhere else. Since the peak before the global financial crisis, US corporate profits have surged by 166% – far outpacing other regions. By contrast, the eurozone has barely moved, with corporate profits up only 8%.

And the profitability of US capital has improved since the end of pandemic slump in 2020. According to calculations by Brian Green, the US corporate pre-tax rate of profit on capital is at a higher level than in 2006.

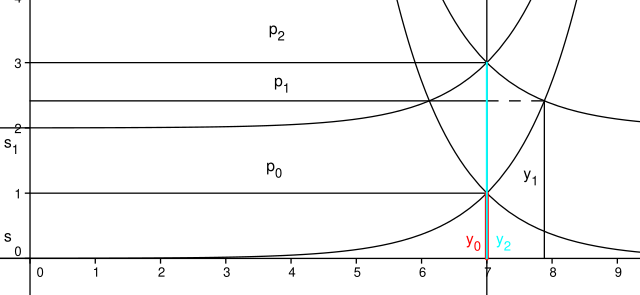

My own calculation for the US rate of profit since the end of the Great Recession and after the COVID pandemic is similar.

Source: EWPT 7.0 series, Basu-Wagner et al, AMECO, author’s calcs

Corporate profits are still growing. Operating income for S&P 500 companies (excluding financials) grew 9% in the most recent quarter, compared with the year before. But that figure includes the mega profits of the so-called Magnificent Seven hi-tech companies. If they are excluded, then the rest of the non-financial, non-energy companies’ earnings growth is about 4-5% and slowing. Profits growth among these companies is being squeezed by rising costs of production rise. That will intensify as the imports tariffs drive up the prices of components and raw materials.

In addition, crude oil prices have been falling and this is reducing profits for the US energy sector. Capital spending on global oil and gas production is forecast to drop 4.3%, the first annual fall in investment since 2020. The energy companies are cutting jobs, slashing costs and scaling back investments at the fastest pace since the pandemic slump. The US shale industry has been hit particularly hard.

Trump and the MAGA team claim that tariffs will bring in so much tax revenue ($1.8trn) and new business investment ($3-5trn extra) that the economy will boom (4% next year, they claim) and that will lead to hundreds of thousands of new jobs. But there is no evidence to support these claims.

Actual tariff revenues total about $134 billion through August 2025. Meanwhile, the federal government budget deficit shows no signs of contracting – on the contrary. Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill Act passed in July promised deficit cuts, but current projections show ongoing deficits. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the federal budget deficit in fiscal year 2025 will be $1.9 trillion. Projected tariff revenues for this year are a tiny proportion of federal government revenues, just 2.4%.

And over the next few years of the Trump administration, corporate tax and income tax cuts for the higher earners will reduce potential revenue much more than increased tariffs will raise. Indeed, these tax cuts will constitute the largest transfer of income by a government from the poor to the rich in a single law in history.

Tariff revenues are not going to reduce the annual federal government deficit currently at over 5.5% of GDP (if slowing slightly). Indeed, projections are for the annual deficits to rise to 5.9% of GDP over the next ten years, with the public debt to GDP ratio heading towards 125% of GDP. The rising public debt ratio is another worry for investors in government bonds and so will drive up bond yields whatever the Federal Reserve does to reduce short-term rates.

American households are feeling the pinch. Consumer sentiment about the economy has fallen to one of its lowest survey readings this century – in line with the Great Financial Crisis levels and the 1980s recession levels.

And the weakest parts of the corporate sector are struggling. There have been 446 corporate bankruptcies year-to-date, the most in 15 years.

I started off this post by arguing that the US economy is entering a period of ‘stagflation’ ie rising inflation and rising unemployment. Stagflation shows that both the Keynesian and monetarist theories of inflation are false. And that means whatever the Federal Reserve does on interest rates or monetary injections will have little or no effect on inflation or employment – the supposed objectives of the central bank.

Whether inflation and unemployment subsides or not depends on whether US real GDP and productivity growth revives or not. That depends on whether business investment continues to grow or not. And ultimately, that depends on whether business profitability and profits are sustained or fall. So far, there has been no fall, but the downward signs are becoming visible.

Be the first to comment