Wealth begets wealth: the wealthiest families in Florence today are descended from the wealthiest families of Florence nearly 600 years ago!

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts Blog

The Medici Family of Florence

Most discussions on inequality, whether between nations globally or within nations, take place around income. Data and papers on inequality of income are profuse, particularly on the rise in most major economies since the 1980s and the cause of it. I have covered many of these papers; the conclusions and causes; in many posts.

Related to the debate around inequality of income is also the issue of ‘poverty’: how to define and measure it and whether poverty globally and within economies has risen or fallen. A recent report by the World Economic Forum, found that income inequality has risen or remained stagnant in 20 of the 29 advanced economies while poverty has increased in 17. Income inequality has increased more rapidly in North America, China, India and Russia than anywhere else, notes the World Inequality Report 2018 produced by the World Inequality Lab, a research centre based at the Paris School of Economics. The difference between Western Europe and the United States is particularly striking: “While the top 1% income share was close to 10% in both regions in 1980, it rose only slightly to 12% in 2016 in Western Europe while it shot up to 20% in the United States. Meanwhile, in the United States, the bottom 50% income share decreased from more than 20% in 1980 to 13% in 2016.”

But discussion and analysis of inequality of wealth (personal wealth) does not get so much attention. And yet, I would argue that anybody with huge amounts of wealth (defined as ownership of property, means of production and financial assets) correspondingly obtains high levels of income – and, it seems, relatively lower levels of taxation.

Of course, there has been excellent work in measuring levels of personal wealth and changes in the distribution of that wealth over time. Every year, I post a report on the Credit Suisse global wealth report, which shows how much personal wealth is held by individuals worldwide. The current score shows that the top 1% of wealth holders have just under 50% of all the world’s wealth. Oxfam regularly publishes data on how just a few families have huge portions of personal wealth in nations and globally. And economists like Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman have produced sterling work in recent years to show the huge inequity in the ownership of the means of production, land, property, financial assets and even patents and ‘knowledge’ products,.

But this is the rub. Both in advanced and emerging economies, wealth is significantly more unequally distributed than income. And the WEF reports that: “This problem has improved little in recent years, with wealth inequality rising in 49 economies.”

In 1912, Italian sociologist and statistician Corrado Gini developed a means of measuring wealth distribution within societies known as the Gini index or Gini coefficient: its value ranges from 0 (or 0%) to 1 (or 100%), with the former representing perfect equality (wealth distributed evenly) and the latter representing perfect inequality (wealth held in few hands).

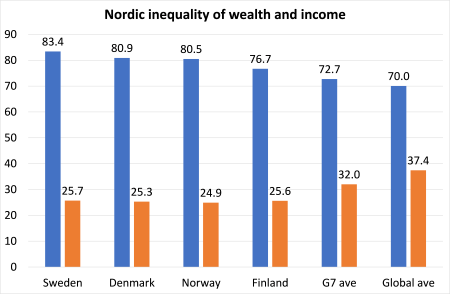

And when you use the gini index for both income and wealth for each country, the difference is staggering. Take a few examples. The gini index for the US is 37.8 (pretty high), but the gini index for wealth distribution is 85.9! Or take supposedly egalitarian Scandinavia. The gini index for income in Norway is just 24.9 but the wealth gini is 80.5! It’s the same story in the other Nordic countries. The Nordic countries may have lower than average inequality of income but they have higher than average inequality of wealth.

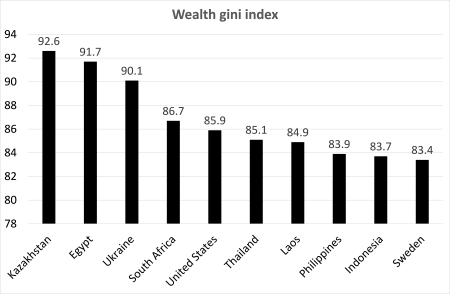

Which countries have the worst inequality in personal wealth? Here are the top ten most unequal societies in the world.

You might expect to find some of these countries listed here in the top ten: ie very poor or ruled by dictators or military. But the top ten also includes the US and Sweden. So, both a ‘neoliberal’ advanced economy and a ‘social democratic’ economy make the list: capitalism does not discriminate when it comes to wealth.

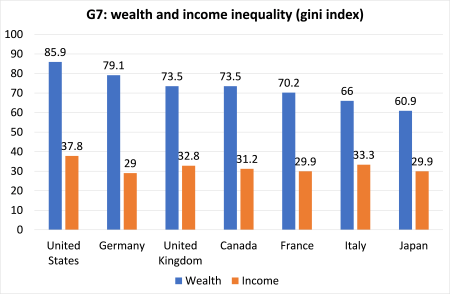

Nevertheless, the US stands out as leader in the top G7 advanced economies in wealth and income inequality.

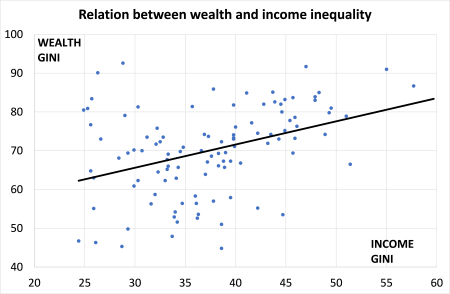

Indeed, can we discern whether high inequality in wealth is closely correlated with inequality in incomes? Using the WEF index, I found that there was a positive correlation of about 0.38 across the data: so the higher the inequality of personal wealth in an economy, the more likely that the inequality of income will be higher.

The question is which drives which? This is easily answered. Wealth begets wealth. And more wealth begets more income. A very small elite owns the means of production and finance and that is how they usurp the lion’s share and more of the wealth and income.

And a study by two economists at the Bank of Italy found that the wealthiest families in Florence today are descended from the wealthiest families of Florence nearly 600 years ago! So the same families are still at the top of the wealth pile starting from the rise of merchant capitalism in the city states of Italy through the expansion of industrial capitalism and now in the world of finance capital..

And talking of the shockingly high inequality of wealth in ‘egalitarian’ Sweden, new research from there reveals that good genes don’t make you a success but family money, or marrying into it, does. People are not rich because they are smarter or better educated. It is because they are either ‘lucky’ and/or inherited their wealth from their parents or relatives (like Donald Trump).

Researchers found that “wealth is highly correlated between parents and their children” and “Comparing the net wealth of adopted and biological parents and that of the adopted child, we find that, even prior to any inheritance, there is a substantial role for environment and a much smaller role for pre-birth factors.” The researchers concluded that “wealth transmission is not primarily because children from wealthier families are inherently more talented or more able but that, even in relatively egalitarian Sweden, wealth begets wealth.”

So Marx’s prediction 150 years ago that capitalism would lead to greater concentration and centralisation of wealth, in particular in the means of production and finance, is borne out. Contrary to the optimism and apologia of the mainstream economists, poverty (in wealth and income) for billions around the world remains the norm with little sign of improvement, while inequality of wealth and income within the major capitalist economies increases as capital is accumulated and concentrated in ever smaller groups. The work of Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman has also shown that, in the US, wealth has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of the super-rich.

Moreover, wealth inequality has risen, mainly as the result of the increased concentration and centralisation of productive assets in the capitalist sector. The real wealth concentration is expressed in the fact that big capital (finance and business) controls the investment, employment and financial decisions of the world. A dominant core of 147 firms through interlocking stakes in others together control 40% of the wealth in the global network according to the Swiss Institute of Technology. A total of 737 companies control 80% of it all. This is the inequality that matters for the functioning of capitalism – the concentrated power of capital.

What that means is that policies aimed at reducing inequality of income by taxation and regulation, or even by boosting workers’ wages, will not achieve much impact while there is such a high level of inequality of wealth. And that inequality of wealth stems from the concentration of the means of production and finance in the hands of a few. While that ownership structure remains untouched, taxes on wealth will fall short too.

Be the first to comment