Economists like to say they’re immune from ideological influence. Our research shows the opposite.

is Associate Professor of Economics at University of British Columbia – Okanagan Campus

Mainstream (neoclassical) economics has always put a strong emphasis on the positivist conception of the discipline, characterizing economists and their views as objective, unbiased, and non-ideological. This is still true today, even after the 2008 economic crisis exposed the discipline to criticisms for lack of open debate, intolerance for pluralism, and narrow pedagogy.[1] Even mainstream scholars who do not blatantly refuse to acknowledge the profession’s shortcomings still resist identifying ideological bias as one of the main culprits. They often favor other “micro” explanations, such as individual incentives related to academic power, career advancement, and personal and editorial networks. Economists of different traditions do not agree with this diagnosis, but their claims have been largely ignored and the debate suppressed.

Acknowledging that ideology resides quite comfortably in our economics departments would have huge intellectual implications, both theoretical and practical. In spite (or because?) of that, the matter has never been directly subjected to empirical scrutiny.

In a recent study, we do just that. Using a well-known experimental “deception” technique embedded in an online survey that involves just over 2400 economists from 19 countries, we fictitiously attribute the source of 15 quotations to famous economists of different leanings. In other words, all participants received identical statements to agree or disagree with, but source attribution was randomly changed without the participants’ knowledge. The experiment provides clear evidence that ideological bias strongly influences the ideas and judgements of economists. More specifically, we find that changing source attributions from mainstream to less-/non-mainstream figures significantly reduces the respondents’ reported agreement with statements. Interestingly, this contradicts the image economists have of themselves, with 82% of participants reporting that in evaluating a statement one should only pay attention to its content and not to the views of its author.

Moreover, we find that our estimated ideological bias varies significantly by the personal characteristics of economists in our sample. For example, economists’ self-reported political orientation strongly influences their ideological bias, with estimated bias going up as respondents’ political views move to the right. The estimated bias is also stronger among mainstream than among heterodox economists, with macroeconomists exhibiting the strongest bias. Men also display more bias than women. Geographical differences also play a major role, with less bias among economists in Africa, South America, and Mediterranean countries like Italy, Portugal, and Spain. In addition, economists with undergraduate degrees in economics or business/management tend to show stronger ideological biases.

We give more details about our methodology and findings in the following sections, but first let us anticipate some of the conclusions and implications. Theoretically, the implications are upsetting for the positivist methodology dominating the neoclassical economics. As Boland (1991) suggests, “[p]ositive economics is now so pervasive that every competing view has been virtually eclipsed.” Yet, the strong influence of ideological bias on views among economists that is evident in our empirical results cannot be reconciled with it.

Practically, our results imply that it is crucial to adopt changes in the profession that protect academic discourse, as well as the consumers of the economic ideas, from the damaging impacts of ideological bias. In fact, there exists growing evidence that suggests value judgements and political orientation of economists affect not just research (Jelveh et al. 2018, Saint-Paul 2018), but also citation networks (Önder and Terviö 2015), faculty hiring (Terviö 2011), as well as economists’ positions on positive and normative issues related to public policy (e.g. Beyer and Pühringer 2019; Fuchs, Krueger and Poterba 1998; Mayer 2001; van Dalen 2019; Van Gunten, Martin, and Teplitskiy 2016). It is therefore not a long stretch to imagine that ideological bias could play an important role in suppressing plurality, narrowing pedagogy, and delineating biased research parameters in economics.

One important step that helps identify the appropriate changes necessary to minimize the influence of ideological biases is to understand their roots.

As argued by prominent social scientists (e.g. Althusser 1976, Foucault 1969, Popper 1955, Thompson 1997), the main source of ideological bias is knowledge-based, influenced by the institutions that produce discourses. Mainstream economics, as the dominant and most influential institution in economics, propagates and shapes ideological views among economists through different channels.

Economics education, through which economic discourses are disseminated to students and future economists, is one of these important channels. It affects the way students process information, identify problems, and approach these problems in their research. Not surprisingly, this training may also affect the policies they favor and the ideologies they adhere to. In fact, there already exists strong evidence that, compared to various other disciplines, students in economics stand out in terms of views associated with greed, corruption, selfishness, and willingness to free-ride (e.g. Frank and Schulze 2000, Frank et al. 1993 and 1996, Frey et al. 1993, Marwell and Ames 1981, Rubinstein 2006, Want et al. 2012).[2]

Another important channel through which mainstream economics shapes ideological views among economists is by shaping the social structures and norms in the profession. While social structures and norms exist in all academic disciplines, economics seems to stand out in at least several respects, resulting in the centralization of power and the creation of incentive mechanisms for research, which in turn hinder plurality, encourage conformity, and adherence to the dominant (ideological) views.

Our own exposure to different parts of this social structure while working on this project has in fact been an unpleasant yet eye-opening experience, and a testament to dominant biases in the discipline that strongly impede critical thinking, new perspectives, and plurality. We have been threatened, accused, and insulted for simply asking an important and legitimate question. We have also had first-hand experience with the Top Five journals in economics and some of their (associate) editors’ exertion of their strong prejudiced views, which is often disguised under the vail of “inevitably subjective nature of editors’ decision-making process,” which is supported by the absolute and unaccountable power that is at their disposal. In some cases, the decision regarding our submission blatantly lacked professionalism and respect for plurality of views.

Our world today is characterized by critical issues that economics has a lot to say about, such as inequality, austerity, the future of work, and climate change. However, relying on one dominant discourse which ignores or isolates alternative views will make the economics profession ill-equipped to engage in balanced conversations regarding these issues. This also makes the consumers of economic ideas skeptical about economists and the views and policies they advocate for. We believe that addressing the issue of ideological bias in economics first requires economists to find out about their own biases. Persistent denial of these biases is going to be more harmful than being aware of their presence and influence, even if mainstream economists do not necessarily change their views. Moreover, the economics profession needs to have an in-depth introspection and a real and open debate about the factors underpinning these biases, including economics training and social structures within the discipline that centralize power, encourage group thinking and conformity, dampen innovative thinking and creativity, and hinder plurality.

Experimental Design

Examining issues such as the impact of bias, prejudice, or discrimination on individual views and decisions is very challenging, given the complex nature of these types of behaviour. This has given rise to a field experimentation literature in economics that has relied on the use of deception—for example, through sending out fictitious resumes and applications, to examine the prevalence and consequences of discrimination against different groups in the labor market.[3] We take a similar approach, namely using fictitious source attributions, in order to investigate the effect of ideological bias on economists (See Section 4 in our online appendix for a more detailed discussion on the use of deception in economics). More specifically, we employ a randomized controlled experiment embedded in an online survey. Economists from 19 different countries were invited to complete an online survey where they were asked to evaluate fifteen statements from prominent economists on a wide range of topics. We received just over 2,400 responses, with the majority of responses (around 92%) from academics with a PhD degree in economics. As reported in our online appendix, our sample includes a very diverse group of economists from a diverse set of institutions. While all participants received identical statements in the same order, source attribution for each statement was randomly changed without the participants’ knowledge. For each statement, participants either received the name of a mainstream economist as the source (Control Group), or an ideologically different less-/non-mainstream economist (Treatment 1), or no source attribution (Treatment 2). See Table A8 in our online appendix for a complete list of statements and sources.

The findings, in detail

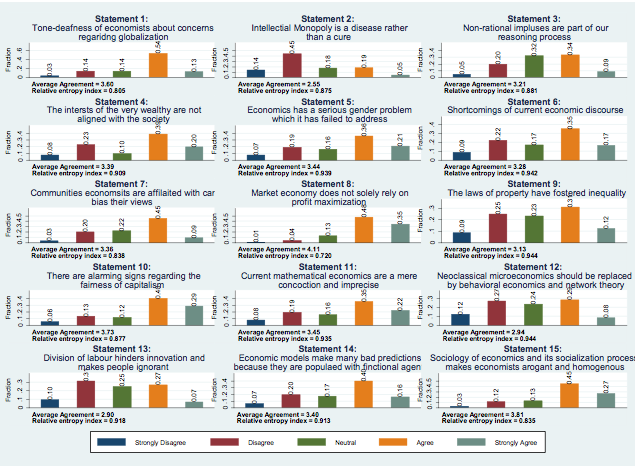

Our analysis of the experimental results reveals several important findings. First, examining the probability of different agreement levels for each statement as well as their comparative degree of consensus (using relative entropy index derived from information theory), we find evidence of clear dissent among economists on the wide variety of topics evaluated (see Figure 1 below). Given that our statements either deal with different elements of the mainstream economics paradigm—including its methodology, assumptions, and the sociology of the profession—or issues related to economic policy, the significant disagreement evident in our results highlights the lack of paradigmatic and policy consensus among economists on evaluated issues.

Figure 1: Probability of different agreement levels – By statement

Note: See Table A8 in our online appendix for a complete list of statements and sources.

Second, we find evidence of a strong ideological bias among economists. More specifically, we find that for a given statement, the agreement level is 7.3% (or 22% of a standard deviation) lower among economists who were told that the statement was from a less-/non-mainstream source. Examining statements individually also reveals that in all but three statements, agreement level drops significantly (both quantitatively and statistically, ranging from 3.6% to 16.6%) when the source is less-/non-mainstream.

For example, when a statement criticizing “symbolic pseudo-mathematical methods of formalizing a system of economic analysis” is attributed to its real source, John Maynard Keynes, instead of its fictitious source, Kenneth Arrow, the agreement level among economists drops by 11.6%. Similarly, when a statement criticizing intellectual monopoly (i.e. patent, copyright) is attributed to Richard Wolff, the American Marxian economist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, instead of its real source, David Levine, professor of economics at the Washington University in St. Louis, the agreement level drops by 6.6%.

Interestingly, these results stand in sharp contrast with the image economists project of themselves in our survey. In an accompanying questionnaire that appears at the end of the survey, a strong majority of participants (around 82%) agreed that in evaluating a statement, one should only pay attention to its content, rather than its author. Only 18% of participants agreed that both the content of the statement as well as the views of the author matter, and only a tiny minority (around 0.5%) reported the views of the author should be the sole basis to evaluate a statement.

Third, we find that economists’ self-reported political orientation strongly influences their views. More specifically, our results suggest that even when we focus on statements with mainstream sources attributed to them, there exists a very significant difference in average agreement level among economists with different political orientations. For example, for a given statement, the average agreement level among economists self-identified as left is 8.4% lower than those self-identified as far left. This already large difference widens consistently as we move to the far right, reaching a difference of 19.6% between the far right and the far left, which is an increase of 133%. This strong effect of political orientation on economists’ evaluation of our statements, which does not change after controlling for a wide set of observed characteristics, is another clear manifestation of ideological bias.

The effect of political orientation on economists’ views is even more drastic when we examine how changes in attributed sources affects economists with different political orientations. More specifically, for those on the far left, altering the sources only reduces the average agreement level by 1.5%, which is less than one-fourth of the overall effect of 7.3% we discussed before. However, moving from the far left to the far right of the political orientation consistently and significantly increases the effect of changing the source to a 13.3% reduction in agreement level, which is almost 8 times (780%) larger compared to the far left. Interestingly, this is despite the fact that relative to the far left, those at the far right are 17.5% more likely to agree that in evaluating a statement one should only pay attention to its content.

Fourth, our results uncover striking differences by gender. More specifically, we find that the estimated ideological bias is 44% larger among male economists as compared to their female counterparts, even after controlling for potential gender differences in observed characteristics including political orientation and political/economic typology. Moreover, our results highlight a startling difference between male and female economists in their perception of gender problems in the profession. When faced with the statement “Unlike most other science and social science disciplines, economics has made little progress in closing its gender gap over the last several decades. Given the field’s prominence in determining public policy, this is a serious issue. Whether explicit or more subtle, intentional or not, the hurdles that women face in economics are very real.”, the agreement level was a whopping 26% higher among female economists than among their male peers.

In addition, when participants were told that the statement was made by the left-wing British feminist economist Diane Elson (rather than the real source, Carmen Reinhart, a mainstream economist at Harvard), male economists showed ideological biases—their agreement level fell by 5.8%. Interestingly, however, it stayed unchanged for female economists. This seems to suggest that the gender problem in economics is so severe that female economists, who exhibited ideological biases on many other issues (although less than did their male colleagues), put aside their biases in this particular case and focused on the content of the statement.

The discussion around the gender problem in economics has recently taken the center stage. During the recent 2019 AEA meeting, and in one of the main panel discussions titled “How can economics solve its gender problem?” several top female economists talked about their own struggles with the gender problem in economics. In another panel discussion, Ben Bernanke, the current president of the AEA, suggested that the discipline has “unfortunately, a reputation for hostility toward women….” This is following the appointment of an Ad Hoc Committee by the Executive Committee of the AEA in April 2018 to explore “issues faced by women […] to improve the professional climate for women and members of underrepresented groups.” AEA also conducted a climate survey recently to “provide more comprehensive information on the extent and nature of these [gender] issues.” It is well-understood that approaching and solving the gender problem in economics first requires a similar understanding of the problem by both men and women. However, our results suggest that unfortunately there exists a very significant divide between male and female economists in their recognition of the problem.

Fifth, we find systematic and significant heterogeneity in our estimated effect of ideological bias by country, area of research, country where PhD was completed, and undergraduate major, with some groups of economists exhibiting little or no ideological bias and some others showing very strong bias.

For example, we find that economists with a PhD degree from Asia, Canada, Scandinavia, and the U.S. exhibit the strongest ideological bias. On the opposite end we find that economists with PhD degrees from South America, Africa, Italy, Spain, and Portugal exhibit the smallest ideological bias. Similarly, our results suggest that there is the smallest ideological bias from economists whose main area of research is history of thought, methodology, heterodox approaches; cultural economics, economic sociology, economic anthropology, or economic development. On the other hand, we find that economists whose main area of research is macroeconomics, public economics, international economics, and financial economics are among those with the largest ideological bias.

We also find that undergraduate training in economics has a strong effect on our estimated effect of ideological bias. We find that those economists with an undergraduate major in economics, or business/management, exhibit the strongest bias, while those who studied law; history, language and literature; or anthropology, sociology, and psychology show no ideological bias. These results are consistent with the growing evidence that suggests economic training, either directly or indirectly, induces ideological views in students (e.g. Allgood et al. 2012, Colander and Klamer 1987, Colander 2005, Rubinstein 2006).

Discussion

Scholars hold different views on whether economics can be a “science” in the strict sense and be free from ideological biases. However, perhaps it is possible to have a a consensus that the type of ideological bias that could result in endorsing or denouncing an argument on the basis of (one’s interpretation of) its author’s views rather than its substance is unhealthy and in conflict with scientific tenor and the subject’s scientific aspiration, especially when the knowledge regarding rejected views is limited.

Some economists might object that economists are human beings and therefore these biases are inevitable. But economists cannot have their cake and eat it too! Once you admit the existence of ideological bias, the widely-held view that “positive economics is, or can be, an ‘objective’ science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences” (Friedman 1953) must be rejected.

Furthermore, the differences we find in the estimated effects across personal characteristics such as gender, political orientation, country, and undergraduate major clearly suggest that there are ways to limit those ideological effects, and ways to reinforce them.

Our finding that those with an undergraduate degree in economics exhibit the strongest ideological bias highlights the importance of economic training in shaping ideological views. In doing so, our study contributes to the literature on economic education, suggesting that ideology can be at least limited by changes in the curricula at earlier stages.

Rubinstein (2006) argues that “students who come to us to ‘study economics’ instead become experts in mathematical manipulation” and that “their views on economic issues are influenced by the way we teach, perhaps without them even realizing.” Stiglitz (2002) also argues that “[economics as taught] in America’s graduate schools … bears testimony to a triumph of ideology over science.”

Economics teaching not only influences students’ ideology in terms of academic practice but also in terms of personal behavior. Colander and Klamer (1987) and Colander (2005) survey graduate students at top-ranking graduate economic programs in the U.S. and find that, according to these students, techniques are the key to success in graduate school, while understanding the economy and knowledge about economic literature only help a little. This lack of depth in knowledge acquired, not only in economics but in any discipline or among any group of people, makes individuals lean more easily on ideology. Frank et al. (1993) similarly highlight the importance of economics training in shaping behavior among students by criticizing the exposure of economics students to the self-interest model in economics where “motives other than self-interest are peripheral to the main thrust of human endeavor, and we indulge them at our peril.” They also provide evidence that such exposure does have an impact on self-interested behavior.

But education is not the only problem: social structures and norms within the profession also deeply influence economists’ adherence to dominant ideological views.

For example, in his comprehensive analysis of pluralism in economics, Wright (2019) highlights several features of the discipline that make the internal hierarchical system in economics “steeper and more consequential” compared to most other academic disciplines. These features include: (1) particular significance of journal ranking, especially the Top Five, in various key aspects of academic life including receiving tenure (Heckman and Moktan 2018), securing research grants, invitation to seminars and conferences, and request for professional advice; (2) dominant role of “stars” in the discipline (Goyal et al. 2006, Offer and Söderberg 2016); (3) governance of the discipline by a narrow group of economists (Fourcade et al. 2015); (4) strong dominance of both editorial positions and publications in high-prestige journals by economists at highly ranked institutions (Colussi 2018, Fourcade et al. 2015, Heckman & Moktan 2018; Wu 2007); and the strong effect of the ranking of one’s institution, as a student or as an academic, in career success (Han 2003, Oyer 2006).

As another example, in a 2013 interview with the World Economic Association, Dani Rodrik highlights the role of social structure in economics by suggesting that “there are powerful forces having to do with the sociology of the profession and the socialization process that tend to push economists to think alike. Most economists start graduate school not having spent much time thinking about social problems or having studied much else besides math and economics. The incentive and hierarchy systems tend to reward those with the technical skills rather than interesting questions or research agendas. An in-group versus out-group mentality develops rather early on that pits economists against other social scientists.” Interestingly, a very similar picture of the profession was painted in 1973 by Axel Leijonhufvud in his light-hearted yet insightful article titled “The life among the Econ.”

It is hard to imagine that the biased reactions we find in our study only emerge in a low-stakes environment, such as our experiment, without spilling over to other areas of academic life. After all, as we discussed at the beginning, there already exists growing evidence which suggests that the political leanings and the personal values of economists influence different aspects of their academic lives. It is also not a long stretch to imagine that such ideological biases impede economists’ engagement with alternative views, narrow the pedagogy, and delineate biased research parameters. We believe that recognizing their own biases, especially when there exists evidence suggesting that they could operate through implicit or unconscious modes, is the first step for economists who strive to be objective and ideology-free. This is also consistent with the standard to which most economists in our study hold themselves. To echo the words of Alice Rivlin in her 1987 American Economic Association presidential address, “economists need to be more careful to sort out, for ourselves and others, what we really know from our ideological biases.”

Notes

[1] Several scholars have highlighted the connection between ideological views and the lack of plurality in economics and the failure of the profession to predict the 2008 crisis, or to even have an honest and in-depth retrospective explanation that would help develop accountable counter-measures against future crises (e.g. Barry 2017; Cassidy 2009; Dow 2012; Freeman 2010; Heise 2016; Lawson 2009; Stilwell 2019). There are also those who believe the 2008 crisis was not predictable, but fault the profession, as Colander (2010) puts it, “for failing to develop and analyze models that, at least, had the possibility of such a failure occurring” (e.g. Cabalerro 2010; Colander et al. 2013).

[2] Even if this relationship is not strictly casual, it suggests that there exists something about economic education that leads to a disproportionate self-selection of such students into economics.

[3] See Bertrand and Duflo (2017) and Riach and Rich (2002) for a review. Also see Currie et al. (2014) as another example of experimental audit studies with deception.

Be the first to comment