A think-piece after a riotous Whitsun weekend. Social credit and the digital central bank money are tools of technocratic social engineers. They want to turn societies into social mega-machines. To prevent this, it is not enough to defend individual freedom against powerful corporations or an encroaching state. We need a vision of a better alternative to social engineering.

Norbert Haering is a business journalist in Frankfurt am Main

Cross-posted from his blog Money and more

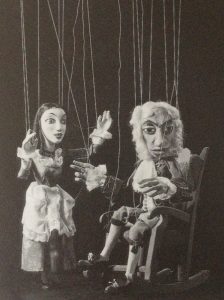

Photo copyright Paul Merkle, Basel und GS Verlag, Basel

Photo copyright Paul Merkle, Basel und GS Verlag, Basel

This blog post deals with an important societal issue with several strands that need to be considered together:

1. Social Credit – Incompatible with Freedom and Democracy

Currently, many regions and municipalities in Europe are testing social credit systems. These include Rome, Vienna, Bologna and Bavaria (in German). The projects are similar. They are organised in each case by those responsible for the digitalisation of public administration. These often have an all too close relationship with the large IT corporations and their lobbies, who provide the necessary know-how and the capacity to implement digitization on a large scale.

In each case, the social credit pilots rely on the monitoring of participating citizens who can get rewards for what the organizers define as virtuous behaviors. They get social tokens into their digital wallets and can exchange these for monetary rewards. Depending on the program, points are awarded for proper waste separation, energy conservation, walking and cycling, using online (instead of in-person) access to government services and paying with cards instead of cash.

As the programs superficially resemble loyalty discounts and customer cards, one might consider them relatively harmless. But when the government sets up such programs, it’s quite different from when a retailer does it.

The retailer is not judging the virtuousness of its customers’ behavior; it is rewarding customer loyalty out of self-interest. A government rewarding virtuous behavior, arrogates the right to define what virtuous behavior is and, using money and power provided by the cintizens, manipulates the behavior of these very citizens with incentives and disincentives. This is contrary to a free, open society and to democratic principles.

In an open, liberal and tolerant society, there are two distinct kinds of social control. Legal commandments and prohibitions ensure that behavior that is grossly detrimental to living together is punished and enforce others that are considered absolutely necessary, such as paying your taxes.

On the other hand, there is an expectation in society that people will adhere to prevailing values and customs, such as politeness and fairness or not wasting energy and resources. The punishment consists in being frowned upon or maybe even shunned by others around you. The more liberal the society, the less rigid these informal rules and the informal sanctions for breaking them tend to be, but the less cohesive society may be. The government is not involved at this level of social control in a liberal society.

When these two kinds of social control are mixed, it becomes very problematic. For liberality or democracy quickly fall by the wayside when a majority the sovereign power of the state to finetune the behavior of a minority, or when those in power instrumentalize prevailing values to control and manipulate citizens’ behavior in pursuit of their own goals.

Such fine tuning of citizens behaviors will easily become a farce when it does not conform to what the government does a the higher level of rules and commandments. This is the case, for example, when people are coerced into funding government subsidies for the automobile industry or (conventional) agriculture, but at the same time can get social credit bonuses from the government if they give up cars or car travel and buy organic food. Or when governments that massively subsidize air travel by exempting aviation fuel from taxes and subsidizing underutilized airports offer virtue bonuses if you don’t fly.

If such contradictory action becomes the norm, and responsibility for the outcome of government action is ascribed to the virtuousness of citizens, how are citizens to meaningfully control and direct government action with a ballot every few years?

If the reduction of CO2 emissions is assigned paramount importance by society, then the government must change the rules in its area of responsibility to meet this goal, rather than devising programs to fine-tune citizen behavior, combining minimal effect with significant intrusion into privacy and private autonomy.

2. Smart City instead of Democracy

The social credit pilot projects are usually integrated into smart city programs. This idea, which is being promoted and pushed by the major US IT companies, is based on using cameras, microphones and sensors to collect and evaluate a maximum of data about a city, its inhabitants and their interactions. The idea is to use this data as a basis for efficiently managing community life by means of artificial intelligence.

In a brochure published by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment in 2017 entitled “Smart City Charta“, one finds, among other things, the following statements:

- Artificial intelligence replaces choice: we never have to decide to take a particular bus or train, but get directed to the fastest route from A to B.

- Behavioral data can replace democracy as the social feedback system. Knowing exactly what people do and want, there is less need for elections, majority rule or voting.

- Through “people-public-private partnerships,” a new form of politics and decision-making may emerge in Smart City 2.0.

- Perhaps private property will become a luxury. Data could supplement or replace money as currency.

- A market only conveys that a person bought this or that; but we don’t know why. In the future, sensors may give us better data than markets.

This brochure was not a one-time slip, now time-barred. The Smart City program continued under Interior, Construction and Home Affairs Minister Horst Seehofer as it did under the current Minister for Housing, Urban Development and Construction, Klara Geywitz. In an ongoing series of “smart city dialogs” and congresses people are exchanging ideas, no doubt generously supported by the IT industry, about how the “sharing” of data and data cooperation across sectors and responsibilities within the city can succeed (and) which technical and contractual models are suitable for a profitable partnership between the public and private sectors within the “smart city”.

The speeches and brochures about Smart Cities are almost exclusively about improving the quality of life and protecting the environment. That the latter may well also mean selecting who is important enough to be allowed into the city center by car or at all is rarely mentioned. Equally rarely mentioned is the totalitarian potential inherent in the surveillance infrastructure that is integral to the smart city (as it is to any social credit system).

Sometimes, however, it shines through between the lines, as in a McKinsey promotional brochure labeled as a study, “Smart cities: digital solutions for a more livable future.” It extols the benefits of smart cities’ surveillance techniques in fighting crime, with “data-driven policing,” including “predictive policing.” This means police preventing crimes before they happen because algorithms alert them to potential perpetrators and crime scenes.

3. Digital central bank money as a smart rationing card

The European Central Bank (ECB) has been working on a digital euro for some time, and the EU Commission wants to create the legal basis for it to be issued as legal tender as early as the first quarter. China is already working with the digital yuan, the US and Britain are in earlier stages of developing a digital dollar or pound.

Digital assets denominated in euros that can be used for payment already exist in the form of bank money, which we use for wire transfers of money or card payments. However, these digital balances on bank accounts legally represent only claims to payment on real (cash) euros from the central bank. Bank account balances are not euros, but obligations of banks to us denominated in euros.

A digital euro, in contrast, is digital money from the central bank with the same legal status as cash. The introduction of a digital euro would mean that we would all have access to such digital central bank money and could pay with it. This could be either directly, via everyman accounts at the central bank, or indirectly, with financial service providers managing escrow accounts for us, through which our transactions would be settled in digital euros.

With a payment system based on the digital euro, the state intervenes as a central middleman in every transaction – at least potentially. It can decide to let private service providers manage the euro accounts and not requesting the data on our payments that accumulates there. it he can gain complete access to all our payments at any time.

The digital euro is supposed to be programmable because, as the EU Commission describes it in its citizens’ consultation on the announced directive, it should also serve the following purposes:

“EU businesses increasingly need innovative payment methods to support their logistics, energy, Internet-of-Things, rental, streaming and other online services and businesses in the new era of Industry 4.0.(…)“

You could program whatever you want into the digital euro, such as: “Transfer 50 cents from her account to the bus company’s account when Ms. x has traveled one kilometer in the buses of bus company y according to the passenger registration, and then 25 cents for each additional kilometer. The flow of data from all the micropayments necessary to make ones way thourgh a future smart city is a dream of every ambitious every social engineer.

If the digital euro is linked to an “identity solution,” as the EU Commission has said it should be, then there are hardly any limits to fine-tuning citizens behvior. As part of the ID2020 program, all people worldwide are to be given a biometric digital unique identity by 2030. This will allow all relevant information about a person to be automatically collected under a unique identification number. This way, computer programs know exactly who is who, who has how many dependent household members and other needs, and everything else they need to know. Now combine that with a programmable money.

Then one can program in that Mrs. x, because she is little health-conscious and expensive for the health system,, and her energy consumption exceeds the norm, will have to pay a surcharge of 20% for each kilowatt hour above the norm and also for products with a red nutrition traffic light. The surcharge can be automatically transferred to the state, the health insurance companies or the Ukraine. However, if her Fitbits or smartphone apps should show in the future that she has exercised diligently and her bank records show that she has bought mostly reasonable foodstuff, a relaxation beckons.

To sum it up: The programmable digital euro enables a social credit system on steroids.

Even better for the social controller: With a digital euro as a smart allocation system, positive and negative incentives can be dispensed with altogether because behavior can be controlled directly. Ms. x can simply be prevented from buying food with a red nutrition light.

A CO2 savings program can also be better implemented with the programmable euro than with any social credit program that merely rewards environmentally friendly behavior. If each product is assigned a quantity of CO2 caused by production, distribution and use by clever experts, a CO2 budget can be programmed for each citizen, which she may not exceed with her purchases, or if they exceed it, a penalty is levied for every kg of CO2, which will go directly to the budget of the government or to some organization doing good work.

Don’t say that it’s an absurd idea that something like this could be introduced in liberal democracies. In Australia and India, welfare recipients get their support digitally, with programmed limits on what they can and cannot buy with it. Such paternalistic control is always first imposed on the weakest members of society.

A whole series of German banks are already levying hidden surcharges, when their cards are used for payments related to gambling. Every commercial customer of the payment service providers has a classification number indicating which industry they belong to. So it is clear from the records whether a payment goes to a retailer, a casino, a jeweler, an escort service, a lawyer’s office or a gun dealer. Nothing fundamental stands in the way of refining the classification more and more.

Food shortages caused by the Ukraine war have helped us to imagine rationing in this area again. Here, too, the programmable digital euro could provide excellent services, as it can act as something like a smart ration card system. Just one pack of toilet paper and one bottle of sunflower oil per account and week can be programmed centrally. The same applies to bread, milk, eggs, gasoline, electricity, and any other product that is in short supply or threatens to become so. With digital money and powerful computer programs fed with lots of data, a centrally planned economy can be implemented very well.

Well targeted, large-scale punitive actions against protesters, as exercised in Canada in February, can be carried out much more smoothly and efficiently with digital central bank money. When the government in Toronto felt cornered by demonstrations and blockades by truckers and by the large public support for them, it declared a state of emergency. Banks were ordered to freeze the accounts of all truckers and any supporters they could locate through their data on wire transfers and other means. This quickly broke the resistance of truckers and the general public.

With digital central bank money, this can be done with much less fuss in the future. If it is previously introduced that people who do unauthorized things can be sanctioned with account suspensions or usage restrictions of varying degrees, the sanctions can be implemented as part of the normal law enforcement program without a need to declare a state of emergency. After all, the government’s central bank as the administrator of accounts, will already have all the information needed.

The beginnings are already visible in Germany. A whole series of operators of critical media have had their accounts terminated by banks without justification. The leading online payment service Paypal is becoming increasingly notorious for freezing credit balances without justification, which are then only recovered after lengthy and costly processes, if at all. It may be enough to receive a payment from China.

4. Pioneer China – From Creditworthiness to Social Credit

It is no accident that the social credit system has “credit” in its name. It is an extension of the credit assessment customary in the financial sector. Before banks give someone credit, they want to be sure that they will get interest and repayment reliably.

For this purpose, credit bureaus collect all data they are able and allowed to collect about a person and use it to determine a score for creditworthiness. In Europe, this is largely limited to financial information because of data protection rules. Where the rules are less strict or not enforeced, lenders or credit bureaus also use data from people’s social media activity or their consumption habits, such as whether they spend too much time playing computer games.

China has taken this to an extreme in pilot projects on social credit and given social credit systems a bad name, at least in the countries of the US sphere of influence, where they have been reported very critically. In China’s own population, on the other hand, the social credit system seems to be popular.

A private project with public blessing was Sesame Credit, a credit ranking system expanded into a social credit system by the Alibaba Group, a corporation that operates the Alipay payment system and leading online trading platforms. Other internet giants such as Tencent also operate such systems. A good ranking was reportedly rewarded with many valuable private and semi-governmental privileges.

However, the Chinese government decided against such a points-based system in 2019. The potential conflicts of interest and possibilities for manipulation for the operators were apparently deemed too great.

However, due to the close cooperation between the government and private corporations in general, and in particular with regard to the social credit system, it cannot be ruled out that the government simply leaves the more sensitive aspects of behaviour management to the corporations under its influence. For example, Alibaba and Tencent were involved in the development of the Corona health code. In many cities, residents were given QR codes on their smartphones that showed their status. They had to show this at checkpoints to be allowed to move around the city. In some cities, such as Hangzhou, the system will continue beyond Corona. A personal health index is calculated from health information and lifestyle.

The focus of the Chinese government is currently on a rather coarse social credit system for enterprises. These are put on public red (good) lists if they dutifully and correctly pay their taxes and comply with the rules for occupational health and safety, or on and black lists if they don’t.

For private individuals, there is mainly a blacklist for people who have not paid important debts, especially to courts. They are pilloried and prevented from travelling long distances. Government critics seem to be disproportionately affected. Since they have a lot to do with the courts, it is relatively easy to arrange for one of their bills to remain unpaid for too long. Recently, people who have given false information about Corona contacts or failed to report an infection have also been blacklisted in some cities.

5. Learning from China

Despite the bad reputation of the Chinese social credit experiments in our sphere, organisations such as the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements are in favour of extending credit ratings in the direction of social credit. The argument is that this would allow people who have no credit history to prove their creditworthiness and get credit.

Despite this bad reputation, social credit pilot projects are sprouting up everywhere in Europe and government agencies are investigating what can be learned from China in terms of social credit. The Bavarian Research Institute for Digital Transformation, for example, has a research team studying the topic: “Learning from the ‘pioneer’? A multidisciplinary analysis of the Chinese social credit system and its impact on Germany“, with question marks and a critical tone, at least in places.

With a much less critical tenor, the University of Vienna is investigating how a trustworthy society can be built with a social credit system, supported with almost two million euros from the EU Commission: “Engineering a Trustworthy Society: The Evolution, Perception and Impact of China’s Social Credit System”. Project leader Christoph Steinhardt writes:

“The Social Credit System (SCS) is an ambitious social engineering project by the Chinese state with the goal of creating a more trustworthy society. It collects information from all citizens, businesses and organizations and seeks to steer behavior through incentives and penalties. The SCS challenges long-standing scholarly assumptions regarding the role of the state in managing social and economic exchange. It has become a central component of the system of governance the Chinese government promotes as a viable alternative to liberal democracy.”

(An equally well-equipped sister project is investigating how the communist one-party government manages to absorb the citizens’ will and prevent uprisings even without democracy).

6. The technocratic world view

Most of those working on technocratic programmes to control and manipulate the population, at least those below the highest decision-making level, do so with the best of intentions to make the world a better place. If you hold the totalitarian potential of their projects against them, they feel maliciously misunderstood, because they are the good guys who only want good things. They do not see that they do not have the power to define what is good for everyone. They feel, that wiith them, such instruments are in good hands and their goals are so beyond doubt that they do not need to be discussed first, not even in a parliament or any other public forum. For them, those who do not share these goals, place themselves outside the supposed social consensus.

The technocrats who devise such programmes and administer them see the world and societies as gigantic machines, composed of individual parts of animate and inanimate matter. Following the laws of mechanics, their interaction will produce a certain action of the machine. Man is reduced to his function as a machine part.

This model of organizing society was particularly evident in ancient Egypt, where the task and result of the social mega-machine was the erection of huge structures that were to provide immortality for the pharaoh. Towards this end-product, the machine was set, into which all available people were fitted, as planners, workers, farmers, craftsmen, soldiers or priests.

The role of the priests was to attribute a spiritual purpose to the machine, such as helping the Pharaoh to eternal, divine life, allowing him to eternally take care of his people and avert harm from them.

In order for the machine to work well, it must be ensured that everyone only does exactly what they are supposed to do. Defective machine parts that work badly or even sabotage, reject the offered doctrine of salvation and call for revolution, must be recognised, repaired or weeded out as quickly as possible, in the well-understood – defined from above – interest of the general public.

Today’s societies are more complex, the incentives and restrictions are softer, the task of creating meaning so that the human-machine parts voluntarily participate is distributed among more institutions. The scope for action of the machine parts is greater, their interaction more flexible. But the idea and approach of the technocrats is the same. It is about optimising a social machine. It would seem ridiculous for its components to have a say in how the machine should work and what it should produce. This would not be compatible with an efficient functioning of the machine.

Data and information about everything and everyone are the be-all and end-all of the social engineer. One can definitely see the potential for abuse. That is why we should be all the more grateful to the well-meaning technocrats that they take it upon themselves to operate the levers without which efficient control of the social mega-machine is simply not possible. For them, the only alternative would be that evil, power-hungry people sit at these powerful levers. They do not even entertain the idea that instead of a social machine there could be a living social organism without such powerful levers and without a predetermined purpose.

The declared goal is to maximise social welfare. Society is fine-tuned to work towards this goal. The exact measure of this welfare, chosen by the well-meaning and clever elites, remains obscure and is not discussed.

The problematic basic assumption is that all cause-effect relationships in the social machine are known or can be objectively determined. They do not change. Everything important can be measured and controlled.

An equally problematic additional assumption is that the elite is altruistic, and it is able to calculate a social welfare function, i.e. to determine what maximises the benefit – however measured – of all members of society in sum.

The altruism of the power elite will probably only exist in individual cases. The saying that power corrupts is not without merit. And that there is not and cannot be a social welfare function should quickly become clear to anyone who tries to find a measure of welfare that allows the happiness, satisfaction, or whatever, of quite different people with quite different preferences, attitudes and goals to be added up. The absence of the assumed social welfare function, however, makes it all the easier for the technocratic elites to claim some nice-sounding goals for their rule. Who is to prove that they are not maximising the welfare of society with their ctions?

Technocratic rule has nothing to do with democracy. It is at best well-meaning dictatorship, at worst dressed-up despotism.

Bill Gates, who became mega-rich with Microsoft and is now co-head of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, provides a prime example of the worldview of the technocratic paternalist in his books and interviews. He publishes books with titles like “How to prevent the next pandemic” or “How to prevent a climate disaster”. In the case of climate change, we are supposed to let him and his similarly influential friends in global governance, i.e. in the World Economic Forum, the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the US government, and so on prevent the catastrophe with new technologies that they develop and finance. In the case of a pandemic, the rescuers will be a global expert commission that identifies disease outbreaks and has all the power to immediately combat them on the ground with drastic measures, in any country of the world.

The German newspaper Die Welt writes about this in a book review (for subscribers):

“Democratic institutions do not appear in Gates’ plan, the word “parliament” appears exactly once in a footnote in the entire book, and it is not without a certain irony that the term “democracy” also appears exactly once – at the end of a list of factors that are apparently not directly relevant to the “problem of preventing pandemics”.”

7. The alternative: social bonds instead of behavioural manipulation from above

The success of the Chinese one-party government in social engineering, and its popularity among the people, exerts a fascination on the technocrats of global governance, who see democratic institutions as troublesome stumbling blocks on the road to improving the world. No wonder, then, that the International Monetary Fund, the Bank for International Settlements, the World Economic Forum and the powerful foundations propagate digital central bank money, social credit systems, global basic income and other instruments of social engineering.

The fact that there is such a need for centralised assignment of trustworthiness in China can be explained by the extremely rapid economic development. This has dissolved traditional social ties at record speed, resulting in a vacuum of trust. To fill this vacuum from above, the communist government and private corporations associated with it have set out to use social engineering.

There is an alternative. But it is unattractive to technocratic rulers. It consists of strengthening social ties, even at the expense of the free but anonymous market. One could think of associations, trade unions, works councils, cooperatives, social organisations, which are not only allowed but also have important tasks, from representing the interests of workers to providing housing, social security and health care.

But promoting and empowering such social bonds runs diametrically counter to the interest of technocratic rulers, who do not like opposition and discussion about their chosen goals. For it would encourage people to unite and engage for common interests, and this can easily go against the government and the elites. For the same reasons, social engineering is popular with those in power.

While many have a problem with technocratic rule, blind spots of the opposing political camps are preventing us from uniting behind a viable alternative vision.

Conservatives, libertarians and many liberals are admittedly comparatively quick to see and criticise the encroachment of the state via social credit systems and programmable central bank digital money. However, because they mistakenly see the “free market” as the counterweight to the encroaching state, they find it all the more difficult to see the alternative in more social bonds in diverse regional, family and issue-oriented communities. They trust “the market” too much to want to extract large areas of life from allocation according to willingness and ability to pay.

Rather, they cling to the illusion that things would get better if the state had less power and “the market” more. They mistakenly equate capitalism with a competitive market economy, ignoring the concentration of market shares and financial power, which has reached an extreme level in recent decades, enabling large corporations to fully harness the state for their own purposes. However, nothing would be better in terms of people’s freedom of action if in China it was not the communist party but Tencent or Alibaba that ran the dominant social credit system and developed a programmable digital money. What is better, if a cartel of social media giants runs a system of censorship in our countries, rather than the government.

The left, on the other side, is more in favour of strengthening diverse communities and in principle also wants to remove important walks of life from the market. But they also misunderstand – with the opposite sign – the nature of the state as an opponent of “the market”, i.e. the big corporations. Due to this misconception, they thin that the state cannot be powerful enough. They mistakenly consider it the exception, not the rule, that corporations seize state power for their own purposes.

And so, when “left-wing” governments follow the whispers of corporate lobbies and privatise housing and housing construction as well as the railways, health care, energy and water suppliers, there is no resistance because the right-wingers like it anyway and the left-wingers don’t want to weaken their beloved government.

The shrinking of areas and relationships of society that function via give and take on the basis of fairness, care and long-term interdependence ensures that modern societies can be controlled so well via the monetary system, for example via programmable money. The weaker the social relations between people become, the stronger state power and money power become.

The problem is not too much individual freedom or too little of it, as the publicist Charles Eisenstein, among others, never tires of pointing out. The problem is that the limitations on individual freedom that are necessary for a healthy society increasingly come from above only. Reciprocal social ties and exchange relations have been weakened too much. We are no longer bonded by diverse decentralised relationships that ensure that everyone feels the consequences of their actions for others and has to answer for them. This creates a lack of control and trust, which technocratically oriented rulers are only too happy to remedy with centralised systems of individual behavior control.

On an individual level, the best way to protect oneself from the whims of social controllers is to build a safety net in the personal sphere through a variety of social ties with the prospect of mutual support when needed. This is worth more than a hoard of bitcoin, gold, food or other prepper paraphernalia. If our account is then blocked, we are not immediately helpless and destitute.

As a society, we achieve this best by removing important areas of life from the market sphere. These include, education, health and housing and by strengthening horizontal social control.

If we implemented both, no one would think we needed a social credit system.

Support us and become part of a medium that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment