When it comes to the German political elite, what matters most is transferring wealth to the rich and themselves, everything else is just a pother.

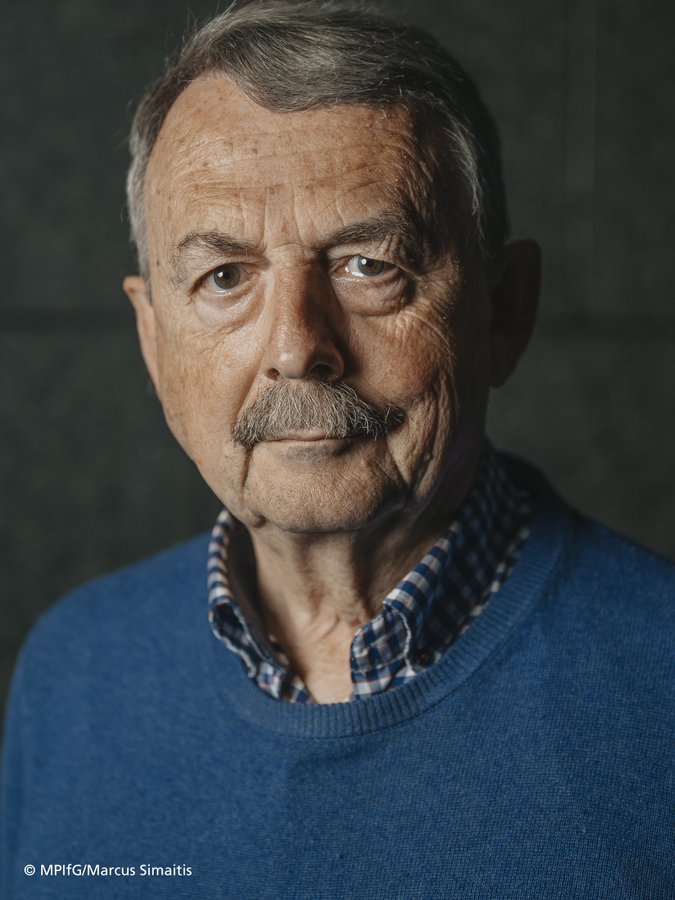

Wolfgang Streeck is the Emeritus Director of Director the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne, Germany

Cross-posted from El Salto

Translation by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

Photo: NATO

What on earth has happened to the “European army”? Some of us can still recall the public appeal, launched three years ago by the philosopher Jürgen Habermas, urging “Europe”, read the European Union, to arm itself to defend its “way of life” against China, Russia and Trump’s country and thereby simultaneously intensify its “ever closer union” in pursuit of the construction of a supranational state. Among the co-signatories of this appeal were a handful of almost forgotten former German politicians, including Friedrich Merz, who was still on Blackrock’s payroll at the time. Here, for once, it is good news: the “European army” is as dead as an army can be and, unlike perhaps the indefatigable Merz, who is now running for the CDU presidency for the umpteenth time, dead beyond any possible resurrection.

What decided its fate? From various points of view, never publicly discussed, as is the new German custom when it comes to matters of life and death, the “European army” project was linked to a long-standing German promise to NATO to increase its military spending to 2 per cent of GDP, i.e., roughly an increase of 50 per cent at some unspecified point in the transatlantic future. It was and is easy to see that this would raise German “defence” spending above that of Russia, not counting spending by the rest of NATO.

It is equally easy to understand that German military spending can only consist of conventional, but not nuclear, weaponry. During the 1960s, West Germany was one of the first countries to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a condition for the Western Allies to allow it to regain some of its sovereignty. On the other hand, it was and is obvious that Russia, with its expensive nuclear force, would be unable to keep pace with Germany in a conventional arms race, which would encourage Russia to invest in improving its “nuclear capabilities”. While this should terrify the bravest among Germans, in fact it does not, since merely mentioning such matters marks you out as a Putinversteher (someone who empathises, understands and puts himself in Putin’s shoes), and who wants to be branded with such a label?

What exactly the 2 per cent was going to be good for, beyond generically adding firepower to “the West”, was never explained, though it was clearly related to the idea of NATO becoming a global intervention force. Note that the German armed forces as a whole, unlike those of other countries, are under the command of NATO, i.e. the United States. It should also be noted, however, that France also wants Germany to strive to reach this 2 per cent.

France itself has fulfilled this percentage for years, which is explained, as in the case of Russia, by the maintenance of its expensive nuclear force and thus the absence of conventional military muscle. Seen from France’s point of view, Germany’s building a non-nuclear military capability does not necessarily benefit the United States, but could, under certain circumstances, also benefit itself, since such a scenario would compensate for its shortfall in conventional armaments caused by its nuclear excess.

This is where the European army of Habermas and friends enters the picture. For the French, what Macron calls ‘European strategic sovereignty’ can only be achieved if Germany disentangles itself from its Atlanticist military involvement, wholly or only in part, in favour of engaging in a Franco-European entanglement. While this is complicated enough, it is impossible without new units and “capabilities” designed from the outset to meet correspondingly specific European objectives, rather than US-determined transatlantic objectives. All that is needed to dismiss this prospect, however, is a glance at German budget planning for the immediate post-coronavirus future (if this scenario ever becomes reality).

According to the current five-year budget forecast, approved by Merkel as chancellor and Scholz as finance minister, defence spending should be reduced from 50 billion euros in 2022 to 46 billion euros in 2025, although at least 62 billion euros would be needed to achieve an increase equivalent to 1.5 per cent of GDP, which is significantly below the 2 per cent target set by NATO. During talks to form the next coalition government, military sources said they had no hope of a consistent change of direction under a government dominated, in their view, by “the left”. According to their view, the only way the German armed forces can repair their supposedly ‘disastrous situation’ – the result of decades of neglect by successive Merkel-led grand coalition governments – under these conditions is to reduce Germany’s military personnel by 13,000 from the current 183,000.

Soldiers, like farmers and ranchers, always complain. No matter how much money they are given, they always feel they should receive more resources. But given the huge deficits envisaged in Germany’s 2020 and 2021 federal budgets, and given the determination of the incoming Scholz government, with Lindner at the head of the finance ministry, to deliver on the debt brake, not to mention the gigantic public investment planned to tackle the coal phase-out and the “digital transformation”, we can fully presume that the dreams of Habermas and Merz cannot be fulfilled, we can safely presume that Habermas and Merz’s dreams of a “European army” were dreamt in vain and that their hoped-for dividends in strengthening “European integration” and stimulating the arms industry will never materialise.

(The coalition agreement of the new German government curiously avoids tackling the 2 per cent issue with a quasi-Merkelian chutzpah: “We want Germany to invest (!!) 3 (!) per cent of its GDP in international action in the long term (!) in a networked and inclusive (!) approach by strengthening its diplomacy and through a development policy, as well as by ensuring the fulfilment of its NATO commitments”. No word on how such an increase will be paid for – will the Americans and the French be fooled).

Among the disenchanted will be Macron, up for re-election in spring 2022, who will not be able to impress his voters with the progress made towards “European sovereignty”, conceived as an extension of French sovereignty, in a scenario where post-Brexit France is the EU’s sole nuclear power and the only permanent European member of the UN Security Council, while German tanks politely complement French nuclear submarines, hoping that the AUKUS fiasco will be forgotten.

Is there any prospect for compensation? Hope, as the German saying goes, never dies, and this may be especially true where France is concerned in European affairs. For the past four years, Germany and France have been talking about the Franco-German fighter-bomber, the Future Combat Air System (FSAC), intended to succeed the French Rafale and the German fighter-bomber Eurofighter Typhoon as the sixth-generation fighter aircraft of the two countries.

The FSAC was originally a Franco-British project, but fell into oblivion in 2017 when the UK opted for its own aircraft, the Tempest. Merkel, urged by Macron, agreed to fill the vacuum left by the UK’s abandonment of the project. In 2018 Dassault and Airbus Defence signed on as its prime contractors and Belgium and Spain joined as participants in the project. However, work was proceeding slowly amid major disagreements, especially over intellectual property rights, technology transfer and, importantly for France, arms export policies. The Merkel government, under pressure from Paris, and probably in line with confidential agreements annexed to the Aachen Treaty signed in 2019, managed to get the Bundestag’s budget committee to authorise a first contribution of 4.5 billion euros to the project in June 2021, thus shielding it from a possible change in the parliamentary majority after the imminent elections in September of the same year.

It is no secret that the FSAC has few, if any, supporters among the German political establishment. This is also true for the German military, which regards it as one of the ultra-ambitious French grand projets doomed to failure due to its excessive technological complexity. The FSAC, which should officially be operational by 2040, consists not only of a fleet of radar-undetectable bombers, but also of countless swarms of unmanned drones that accompany the aircraft on their missions. It also has satellites to support both the bombers and their drones and has cyber-warfare devices useful to the system as a whole, lending it an air of science fiction that unflappable German generals tend to find frivolous to say the least.

Recently, the German General Audit Office has felt, in a confidential report, that it should reprimand the government for leaving crucial issues unresolved in negotiating the deal, while the Bundeswehr [German army] procurement agency has expressed doubts as to the plausibility of the FSAC ever becoming operational. The FSAC will undoubtedly be an expensive project. Reasonable official and semi-official estimates today put the cost at 100 billion euros, while those involved in the project at Airbus believe the bill will ultimately be three times higher. By comparison, the Next Generation European Union Recovery Fund, set up to combat the effects of the coronavirus and divided among the 27 Member States, amounts to 750 billion euros.

Could the FSAC be Macron’s consolation prize to make him forget about the “European army” and “European strategic sovereignty”? Maybe, if there were still more money in the pipeline, but hardly now after the great bloodletting of the coronavirus. In Germany the FSAC is seen more as a complication than a strategic or industrial opportunity: one of the many problems bequeathed by Merkel’s inimitable ability to make incompatible and unrealisable promises and then get rid of them while she was chancellor.

Although there are still some ‘Gaullists’ in the German political class for whom the alliance with France, leading at best to a Franco-German or German-French Europe, predominates over the alliance with the United States, none of them will be present in the new government. In fact, where the coalition agreement could have spoken of a “European army”, it merely provides for “increased cooperation between the national armies of the Member States of the European Union […] in particular as regards training, capabilities, interventions and equipment, as is the case, for example, with the cooperation designed by France and Germany”.

In order to avoid confusion, it adds that “interoperability and complementarity with NATO command structures and capabilities must be ensured in this respect”, stating even more explicitly a few pages later: “We will strengthen NATO’s European pillar and work towards closer cooperation between NATO and the European Union”. The FSAC is not even mentioned, or only indirectly in language that can only hurt French feelings: “We are strengthening defence technology cooperation in Europe, notably through high-quality technology cooperation projects, taking into account national core technologies and allowing small and medium-sized enterprises to compete with each other. Replacement purchases and off-the-shelf systems should be prioritised to meet the supply needed to avoid capability problems”. It is very likely that the FSAC project, if it does not fail because of technological problems or disagreements over industrial leadership and patent rights, will be abandoned at one point or another because of its cost.

Scepticism about the FSAC reigns not only in the SPD, but also in the FDP. The next foreign minister, the unsuccessful Green chancellor candidate Annalena Baerbock, is a convinced Atlanticist of the Hilary Clinton type, who managed to impose her views throughout the document drawn up to form the new coalition government. During the talks that accompanied the negotiations, the Greens insisted on the early replacement of the Luftwaffe’s ageing Tornado fleet with the US F-18 fighter-bomber. The Tornados, not to be confused with the Eurofighter Typhoon, are Germany’s contribution to what NATO calls “nuclear participation” (nukleare Teilhabe). This allows certain European member states, notably Germany, to equip their own bombers with US nuclear warheads under US permission and direction. (As we know, the United States or NATO cannot formally order member states to use nuclear weapons against a common enemy, but they cannot use them without US authorisation). ) To this end, the United States maintains an unspecified number of nuclear bombs on European soil, especially in Germany.

Recently leading SPD figures have doubted the relevance of nuclear engagement. The US for its part has complained about the Tornados, which first entered service in the 1980s and are out of date, demanding more comfortable travel conditions for their ballistic warheads. Currently the few Tornados capable of flying, said to number fewer than two dozen, are set to lose their (US) licence to kill in 2030. Unless the programme is allowed to die out, which is what some left-wing SPD representatives prefer, the Tornados could in principle be replaced by the French Rafale or the German Eurofighter Typhoon, which should in turn be replaced, in a nebulous future, by the FSAC. It turns out, however, that in order to carry US bombs, non-US aircraft must be certified by the US, which, it is said, takes time, say eight to ten years. This fact puts the F-18 on the scene, since it would be instantly available to inflict nuclear Armageddon on anyone the POTUS might deem worthy. It is possible that the F-18 is the preferred choice of the German military, desperate to preserve its reputation in the eyes of its US idols and anxious to avoid the risks of France’s fiendish technological complexity.

To their relief, the immediate supply of a generous fleet of F-18 aircraft turned out to be one of the demands most inflexibly fought for by Baerbock’s Greens during the talks to form the new coalition government. After inclement negotiations, they got their way. In the coalition agreement, in language only comprehensible in its entirety to the initiated, the parties announced that at “the beginning of the 20th parliamentary term [one has to Google that this is the one that starts now] they are committed to procuring a system to replace the Tornado fighter-bomber” and “to objectively and conscientiously accompany the supply and certification process, taking into account Germany’s nuclear participation”. With the F-18 not exactly cheap for a cash-strapped government, this is bad news for Macron and his “European strategic sovereignty”. While the US will not get its 2 per cent military spending from Germany, it can at least manage to sell it a reasonable number of F-18s. France, conversely, is likely to end up empty-handed, getting neither the European army nor ultimately the FSAC.

Wolfgang Streeck

MPIfG/Marcus Simaitis

Be the first to comment