Italy’s recovery must be considered a central task of European economic policy. Mario Draghi’s start as prime minister should be seen as an opportunity for a “New Southern Policy”.

Philipp Heimberger is Economist at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw)

Nikolaus Kowall is Professor for International Macroeconomics

Italy – heavily in debt and still unwilling to reform! Over recent weeks, countless articles have again been written about our EU partner country that struck such a tone. In fact, we were rarely able to read anything positive about Italy in the media over the last year. First, the negative health effects of coronavirus hit the country particularly hard during the first phase of the pandemic. Then came the severe economic crisis with discussions about European response packages, during which journalists as well as leading politicians of the self-proclaimed “frugal four” repeatedly questioned whether Italy should really receive grants to a considerable extent to mitigate the consequences of the COVID19 crisis. And then Guiseppe Conte’s government had to step down after former Prime Minister Renzi removed his party’s two ministers from the government, leading to intense discussions about a political crisis in Italy.

Now there is a new Italian government under prime minister Mario Draghi, the former ECB president. This government will not only have to deal with the pandemic, but also with planning the use of around €200 billion from the EU recovery fund for the coming years. In view of these important political projects, it is high time to take a fact-based look at Italy and, in doing so, also dispel some myths that unfortunately continue to be spread regularly by journalists and media.

So here are seven stereotype-defying pieces of data about Italy.

1. Italy has been living below its means

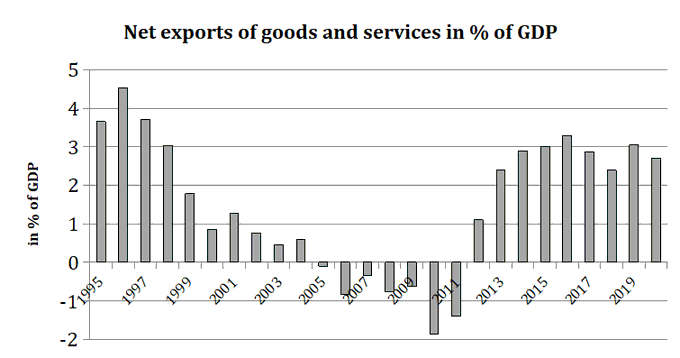

‘Italy is living beyond its means!’ This statement is often justified by pointing out that Italy’s public debt has risen to around 160% of economic output, not least due to the effects of the Covid pandemic. Yet this means only that the public sector is highly indebted—it says nothing about the Italian economy as a whole. For a country can only really live beyond its means if it imports significantly more goods and services than it exports over a longer period of time, which goes hand in hand with rising foreign debt. If, on the other hand, roughly the same amount is exported as is imported, it makes little sense to speak of “living beyond one’s means”, because production and consumption match. And in Italy it is even the case that since 2012 the country has recorded higher exports of goods and services than imports. The country consumes less than it produces and is a net exporter of capital. So if anything, Italians are not living above their means, but below their means.

Source: AMECO (Autumn 2020), own calculations.

2. Private debt is relatively low in Italy

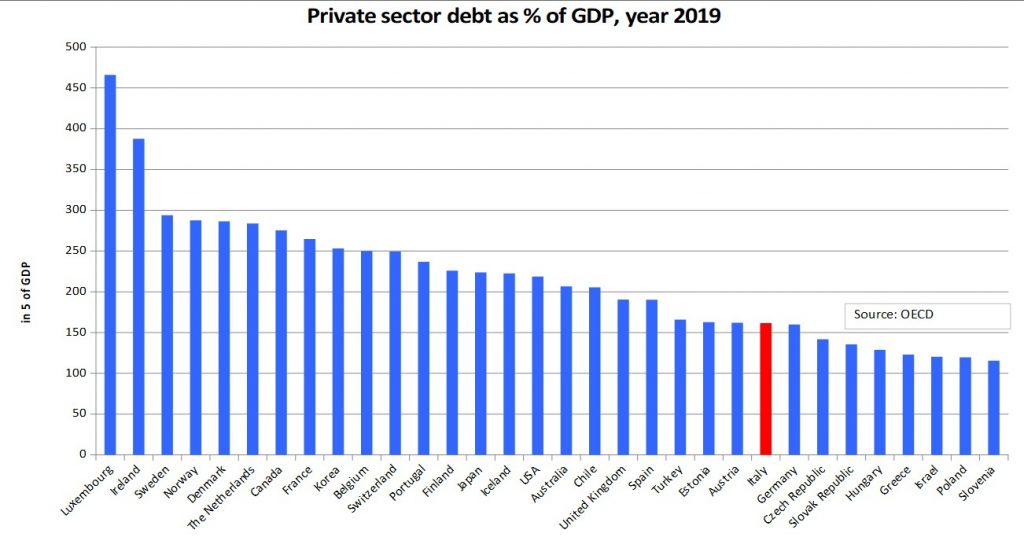

If the Italian economy as a whole is not living beyond its means, then the high level of debt must be confined to the public sector. And so it is, private debt in Italy is low by OECD standards. In other words, overall debt is certainly not a bigger issue in Italy than in other European countries.

Source: OECD

3. Public debt is high because of errors made 40 years ago

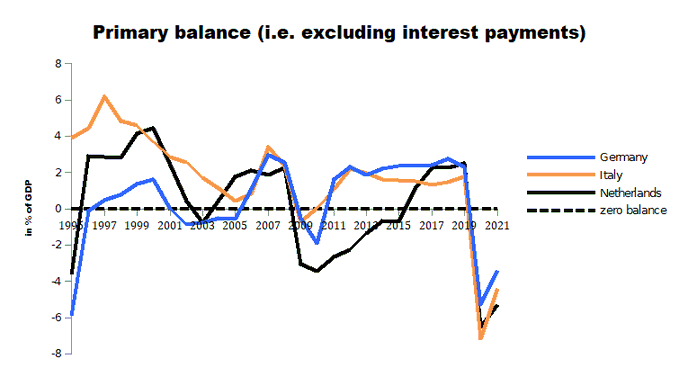

If the economy is not excessively indebted, why is the state so ailing? As disastrous as the performance of Italian domestic politicians from Silvio Berlusconi to Matteo Salvini has been, high public debt is primarily a legacy from the 1980s. Furthermore, the mistakes that were made 40 years ago took place in an international environment of increasing interest rates. Since then, the Italian state has been carrying a heavy interest-rate backpack. If we exclude the burden of interest rates, however, the Italian state has been consistently running budget surpluses since 1992 (with the exceptions of the financial crisis year 2009 and the COVID crisis year 2020).

Even Germany, Austria and the Netherlands have recorded a comparable positive ‘primary’ budget surplus less frequently than Italy. The Italian state has not been as ‘profligate’ as is often claimed: it has consistently collected more in taxes than it has spent. But the interest burden—high due to legacy debt—has repeatedly pushed the overall budget balance of the Italian state into negative territory. Yes, Italy is running significant fiscal deficits in 2020 and 2021, but this is due to the effects of the COVID19 crisis, which is also having a strong impact in other EU countries.

Source: AMECO (spring 2020), own calculations.

4. Italy’s economy has suffered since joining the euro

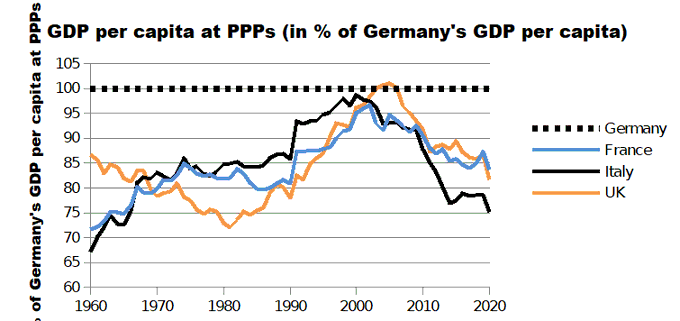

Italy’s public debt is also marked because its economic growth has been so weak over the last 20 years—being presented as a ratio to GDP, if the economy stagnates a state cannot grow itself out of a pool of debt, which already stood at 120 per cent of GDP in 1995. In this context, policy deficiencies, including vis-à-vis corruption and organised crime, should not be neglected. But Italy has never been a haven of political stability. The new Draghi government is the 67th since the war—and mafia and corruption have long been embedded. Yet this did not hinder the Italian economy from developing quite dynamically at times.

Italy overtook the United Kingdom in 1969 and France in 1979 in per capita purchasing power. In 2000, Italy’s average standard of living was virtually equal to that of Germany (98.6 per cent of its GDP per head). But after the introduction of the euro in 1999, the country fell behind the UK (in 2002) and France (in 2005) once more. By 2020, Italian per capita income was about 25 per cent below that of Germany.

In the case of Italy, it is very striking that the commitment to the Maastricht criteria and the process of introducing the euro in the 1990s went hand in hand with the decline in economic growth and increasing productivity problems. One explanation is that being bound by European budget rules has reduced domestic demand in Italy and thus also contributed to the stagnation of the economy. Moreover, the value of the euro reflects the average strength of all Eurozone economies. The common currency is too cheap for Germany (which boosts German exports) and too expensive for Italy.

Whether Italy can ever regain economic momentum within the euro area will depend not least on the willingness of Germany and other European countries to reform the institutional euro architecture in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis – especially where budget rules are concerned. In any case, it is clear that countries like Germany, the Netherlands or Austria, which have benefited greatly from the “cheap” common currency, should do everything they can to keep Italy in the euro area. That would be in their own interest, because a return to an “expensive” currency like the D-Mark would be a major price burden for the industry of countries that depend on an export-led growth model.

Source: AMECO (Autumn 2020); own calculations.

5. Italy has carried out many market-liberal reforms

In 2015, the OECD assessed Italy’s ‘reform efforts’ as significantly stronger than those of Germany and France. The Dutch economist Servaas Storm takes a similar line. In an in-depth study he finds that Italy has adhered much more closely to the EU’s policy rulebook than Germany or France. We have already established that the Italian state has recorded greater fiscal consolidation efforts than all other European partners before the COVID19 crisis—at a high price.

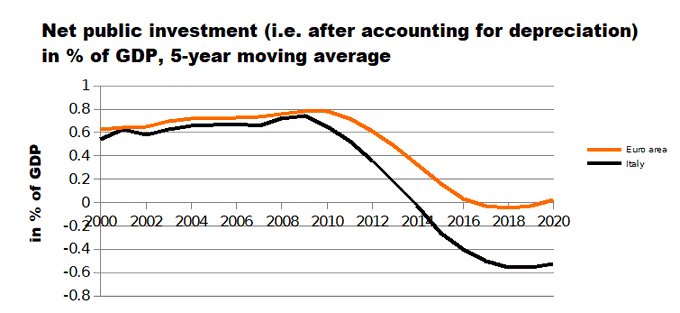

This is because fiscal consolidation has weakened domestic demand for goods and services, and consequently growth, to such an extent that debt has remained high despite large fiscal consolidation efforts. Italy’s austerity policy also had very concrete consequences. On the one hand, it led to severe cuts in the health care system, which proved fatal in the Covid19 crisis. Moreover, a drastic decline in public investment has hampered productivity growth in Italy.

But it was not only in the area of public finances that Italy was particularly eager to comply with EU requirements. An equally EU-compliant flexibilisation of the labour market brought a sharp increase in fixed-term contracts, a pushback against trade unions and a decline in real wages compared to Germany and France. Most recently, in 2014, under Matteo Renzi, employment protection was strongly reduced. These measures not only reduced inflation in the 1990s, but arguably also unemployment, which was finally lower than in Germany and France when the financial crisis broke out in 2008. But cheap labour has also reduced the incentive for labour-saving investment by companies. This private investment, however, is key to rising productivity and is particularly crucial in high-tech sectors. Productivity development is in turn the basis for growth and rising incomes. Both large fiscal consolidation efforts and market-liberal structural reforms have thus arguably done more harm than good to Italy’s productivity growth.

Source: AMECO (Autumn 2020); own calculations.

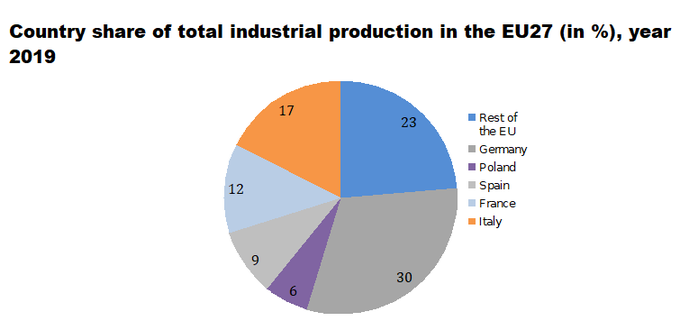

6. Italy remains the second most important industrial country in the EU

It may sound surprising to northern-European ears but, despite weak productivity growth and problems with price competitiveness within the euro area, Italy has important economic strengths. The 60 million Italians do not live primarily from tourism. Italy is still the second most important industrial location in the EU (which would be true even if the United Kingdom were still part of the EU), mainly due to the economic structure in the north of the country.

The country has the second highest industrial production after Germany and exports significantly more industrial goods than it imports. By far the most important export sector is mechanical engineering, which alone accounts for almost one fifth of goods exports – followed by vehicle construction and pharmaceutical products. The order is almost identical to Germany’s export structure and these sectors rank under “medium-high-tech” to “high-tech” industries in the OECD’s classification. The historically grown industrial structure of (Northern) Italy is just one example of the great economic potential of our southern EU partner country. If austerity policies and market-liberal reforms have failed to move the country forward over the past decades, then the obvious thing to do is to try an investment strategy – for which the use of money from the EU recovery fund could provide a first impetus – and give Italy’s industry a boost by launching a modern European industrial strategy.

Source: Eurostat.

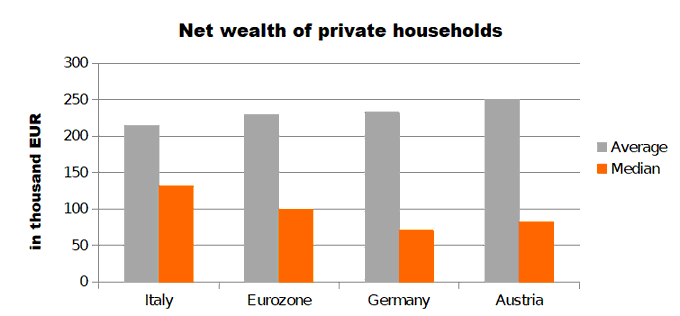

7. Italians are not richer than Germans or Austrians

Over the last year, we have also often heard the argument that Italians are wealthier than Germans or Austrians. Therefore, they should pay for their investments themselves! The median Italian household, that located exactly between the richer upper half and the poorer lower half of the population, is indeed wealthier than the corresponding German or Austrian household. But the average Italian household—obtained by dividing the total net wealth by the total number of households—is clearly less wealthy than in Germany or Austria.

Although private wealth is lower in Italy, wealth distribution is more equal; in Germany and Austria, wealth is more heavily concentrated in richer households. One of the main reasons for this is that private-property ownership plays a greater role in Italy. This has a lot to do with the relative underdevelopment of the public safety net: social and co-operative housing, which provides many people in Germany and especially in Austria with affordable housing of a reasonable size, is rare. Social housing and co-operatives do not however count as private assets, even if people there live occasionally more comfortably than in Italian condominiums of poor standard. But it remains simply wrong to say that Italians are wealthier than Germans or Austrians.

Source: ECB

A strong Italy in a strong EU

Italy certainly has significant structural problems, such as the oversized banking sector, the North-South divide, organized crime or dysfunctional political elements. The question is: Under what conditions is the country better able to tackle these problems? In this country of 60 million people, the stagnation of the last 20 years has been a breeding ground for fatalism rather than optimism. All the more reason for media and politicians in Germany, Austria and beyond to refrain from treating Italy like a hopeless case – a southern European patient who is having problems because he refuses the reform medicine of the northern European doctor.

The European media, as well as Europe’s key leaders, invoke international competition between the EU and China and the United States. A logical geopolitical conclusion from this would have to be to actively support the Italian economy, which used to be the second largest in the EU, in its recovery efforts – for example by launching a modern industrial policy strategy. This measure alone would significantly strengthen the EU’s economic weight in the global economy. If Italy had grown as fast as Germany or France since 2000, the EU’s GDP (in World Bank purchasing power parities) would be higher than that of the US, not lower. A strong Italy in a strong EU would also be in the interest of all those who consider such international economic rivalries to be contrived, but who want Europe to preserve its social model of a liberal democracy of social balance in the 21st century.

The pandemic is not over; the economic consequences will be felt for a long time. The economic recovery of Europe is an opportunity to trigger a sustainable economic development of Italy. Until the Covid19 crisis, Northern Europe was holding up quite passably economically by international standards, and the economic integration of Eastern European member states was mostly positive. Today, the breaking point of the euro area and the EU is Italy and Southern Europe. From a European perspective, Italy’s recovery must be considered a central task of economic policy. Mario Draghi’s start as prime minister should be seen as an opportunity for a “New Southern Policy” in the coming years – both on the part of the EU Commission and the German government.

Be the first to comment