Insight into the recent surprise election results in Catalonia and what might follow

Antoni Soy is Honorary Professor in Economic Policy at the University of Barcelona

Edited by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

Puede leer este artículo en catalan aqui

The regional elections to the Parliament of Catalonia were held on 14 February. The conditions were not the most favourable for holding an election: a government without a president who had been disqualified by the Spanish courts; a government that had long-lived in the constant quarrels between its partners; a pandemic with too high numbers of deaths, positive cases, people in hospitals and Intensive Care Units (ICUs); very serious economic and social crises -with the background of the ecological crisis, with the economy half paralysed and with a significant increase in people in a situation of unemployment (especially young people), poverty (in too many cases extreme) and , therefore, with little chance of being able to have a dignified life; to make matters worse, the Spanish courts had obliged to hold elections on that date while the Catalan government wanted to delay them at a time when there were already more people vaccinated (and therefore perhaps fewer people are infected in hospitals).

This whole picture, along with the ongoing repression against pro-independence activists and social movements (for housing, for overcoming the climate crisis, for changing the economic model to one that puts people’s lives at the centre, and so on), and with a certain tiredness on the part of the population because the conflict between Catalonia and Spain continues, at least apparently, stagnant and without a way out of the situation, they help to explain, it seems to me, the high level of abstention (46.5%), more than 25% higher (over 1.3 million people) than in the previous elections in 2017. An abstention that has affected a little more the so-called unionist or monarchist parties than the pro-independence parties.

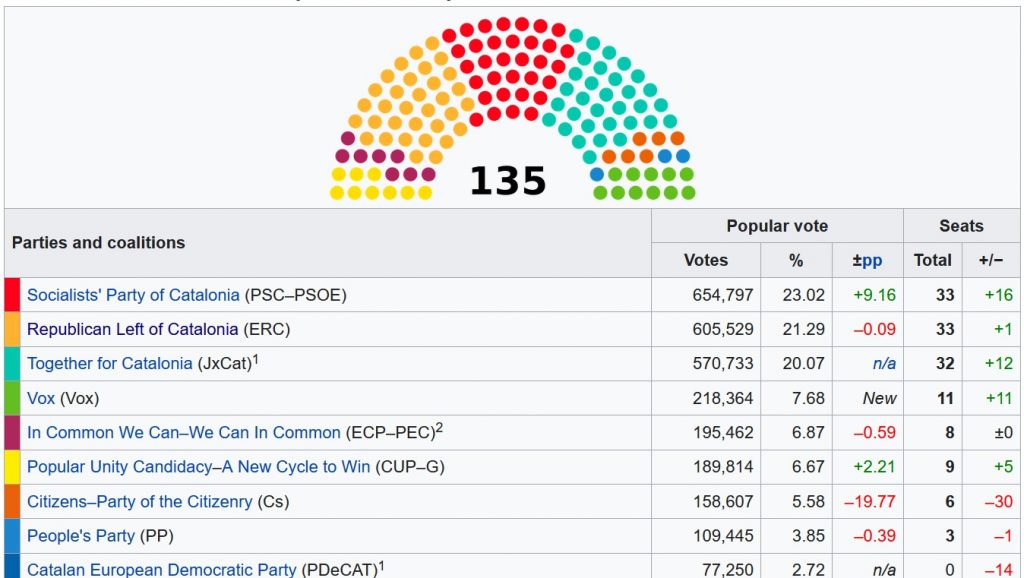

The party that has won the most votes and the most seats (in this case tied with the second) has been the Spanish Socialist Democrats (PSOE), a unionist party, monarchist, and with a fundamental action because in Spain, in some areas and aspects, there has not been a radical break with the forty years of Franco’s dictatorship. They have garnered most of the unionist vote (almost as many as the rest of the unionist forces put together). However, it is very difficult, practically impossible, due to parliamentary arithmetic, for its leader to be the president of the Catalan Generalitat (state), and it does not even seem easy for him to be part of the government that is being set up. This is not to say that, as the first party in the unionist bloc, it cannot play an important role, even by agreeing or influencing some laws and reforms proposed by the regional parliament.

As for the other unionist and monarchist parties, all more to the right of the PSOE, the most notable is undoubtedly the huge blow of neo-liberal Ciudadanos (C’s), which lost almost a million votes and 30 seats, and goes from being the strongest party, with regard to votes and seats, in 2017, to be the seventh force in Parliament with only 6 seats. For its part, the centre-right and notoriously corrupt Popular Party (PP) also lost votes and a seat having only 3 deputies left, which will not permit it to have its own parliamentary group. The second notable thing is the strong entry of the far right of VOX, with more than 217,000 votes and 11 deputies, making it the fourth strongest party in Parliament.

It is not easy to talk about the Comuns-Podemos because, theoretically and until now, they had tried to maintain equidistant between the two blocs (since it seemed that, despite the preponderance of the unionists, there was a significant percentage of pro-independence), calling themselves sovereignists (a concept that no one, I think, has ever been able to define, but which, in any case, does not coincide with that of sovereignty in different areas). However, for some time now, and especially in this election campaign, it seems that the primacy of the unionists, in number but also in the message and the discourse being transmitted, is becoming increasingly important. Well, they lost almost two hundred thousand votes and were left with the same number of deputies (8).

If we look at the pro-independence bloc, the first thing to note is that the pro-independence parties have clearly won the election with 51.6% of the vote (for the first time above 50%) and with 74 deputies (the absolute majority is in 68 deputies). Secondly, it is worth noting the change in the party with more votes (despite having lost more than 330 thousand) and with more seats (33, one more than in 2017 and tied with the PSOE) has been the social democratic ERC, for the first time since the so-called transition. The social liberal Junts per Catalunya has moved to second place with 32 deputies (2 less than in 2017) and having lost about 380 thousand votes. As for the leftist CUP, it achieved a very good result with 9 deputies (more than double of those it had previously) and losing just over six thousand votes. Finally, the Catalan very conservative PDeCAT, the heirs of the former CiU and with the leadership in the shadow of the former president of the Generalitat, Artur Mas, have received more than 77 thousand votes, but have been left without parliamentary representation, so we will have to be very attentive to what will be the future of this party that, at this moment still has a good number of mayors and councillors.

From this, what pacts can be envisaged when forming a government? One option, given that they are pro-independence parties, have won more than 50% of the vote and have a clear majority of deputies, would be an ERC-Junts-CUP pact, with a government involving the first three or only the first two; the main drawback of this formula is, surely, that ERC and Junts have been in government in the last legislature and have had major disagreements and quarrels, and that they have policies that, in many areas, the CUP does not share at all. Another possibility that would also have an absolute majority is what the Comuns-Podemos call a left-wing government formed by ERC-PSOE-Comuns (and it is not known if the CUP, but in any case the Comuns do not talk about it); I think it is a theoretical possibility, but in practice it is very difficult for the ERC and PSOE to share government at the moment, as they are separated by fundamental things such as the amnesty of prisoners and exiles, the right to self-determination, etc. A variant of this option would be that of an ERC-Comuns minority government that for essential reasons could have the external support of the PSOE symmetrically to what is happening in Madrid; it seems difficult, however, for both the CUP and Junts to support a government of this type that depended on the external support of the PSOE, a party that keeps Catalan political prisoners and turned other Catalan leaders into exiles. Another possibility of minority government, advocated by some commentators and “think tanks”, is that of an ERC-CUP-Comuns government, which should seek variable support from Junts and the PSOE depending on the issues at stake. Finally, from ERC there has been talk of the possibility of a government alone that would expect to receive variable support depending on the circumstances and issues, from the PSOE, Junts and the CUP, a bet that, in principle, seems very risky. In conclusion, there is not a clear or easy situation for having a new government. We will see how the negotiations progress and materialize.

Be the first to comment