Private debt is the real problem, and a solution

Steve Keen is an Australian economist and author. A post-Keynesian, he criticizes neoclassical economics as inconsistent, unscientific and empirically unsupported.

Cross-posted from Steve Keen’s Building a New Economics

Debt by Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 Pix4free

Not a day—barely a second, it seems—goes past without some sage warning about the dangers of America’s huge government debt.

On the other hand, you barely even hear a mention of private debt. So government debt must be far bigger than private debt, rights.

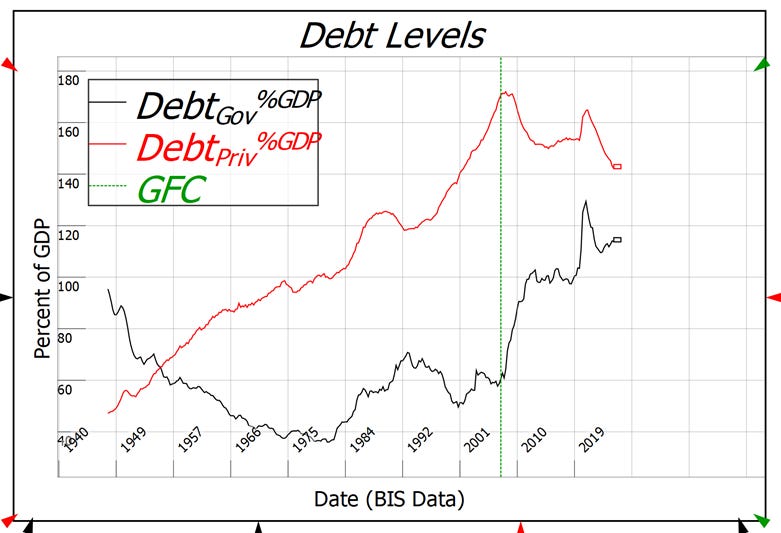

Wrong. In the USA, and almost all developed countries, private debt is way bigger than government debt. As Figure 1 shows, before the Global Financial Crisis, government debt was relatively low—just 60% of GDP—while private debt, at 170% of GDP, was almost 3 times higher. Government debt has risen since, both in reaction to the GFC, and because of Covid. But even so, it’s still lower than private debt.

Figure 1: USA Private Debt is far higher than Government Debt

So why don’t we hear about the dangers of private debt? It’s because, according to mainstream economists, there are no dangers.

This is completely wrong, as the data shows. Economic crises are caused by excessive private debt, not excessive government debt. They occur when credit—the rate of growth of private debt—turns negative, at a time of already high private debt.

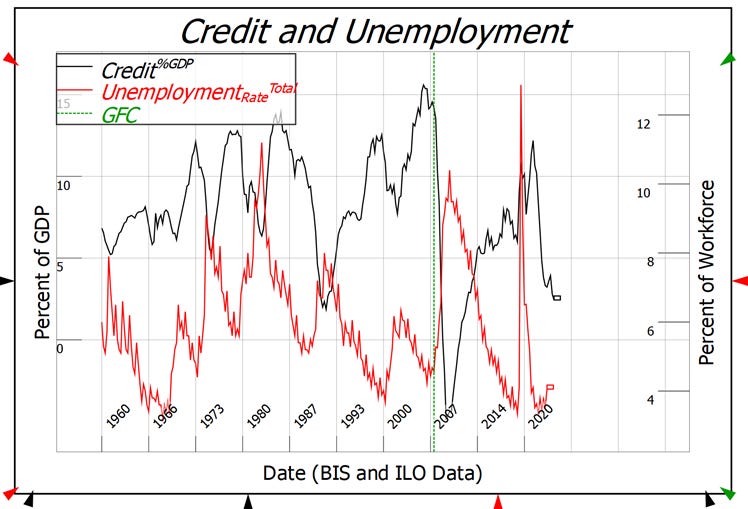

The economic boom before the GFC was caused by credit rising from just 2% of GDP at the end of the 1990s recession, to 15% of GDP at the height of the Subprime Bubble in 2006. Then credit plunged from plus 15% of GDP in 2006 to minus 5% in 2009. This is what caused the GFC (or “The Great Recession”, as Americans call it): see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Credit drives macroeconomic activity

The first person to realize that private debt, not government debt, was the main cause of economic depressions, was not Keynes, but Irving Fisher.

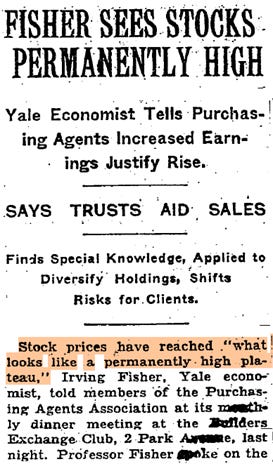

Unfortunately, these days, Fisher is most remembered for his statement, just before The Great Crash, that “Stock prices have reached a permanently high plateau”, and that he expected “to see the· stock market a good deal higher than it is today, .. within a few months”. One week later, the market fell 10% in one day, and he was wiped out.

Figure 3: Fisher’s “permanently high” prediction, published in the New York Times on October 16 1929, just days before stocks fell 10% on “Black Tuesday”

But in the aftermath of The Great Crash, Fisher realised that what had led him astray was the Neoclassical assumption that equilibrium was the rule in a capitalist economy. Instead, disequilibrium was the rule. He reasoned that, even if you assume that economic variables tended towards equilibrium…

New disturbances are, humanly speaking, sure to occur, so that, in actual fact, any variable is almost always above or below the ideal equilibrium…

Theoretically there must be over-or under-production, over- or under-consumption … and over or under everything else. It is as absurd to assume that … the variables in the economic organization … will “stay put,” in perfect equilibrium, as to assume that the Atlantic Ocean can ever be without a wave. (Fisher 1933)

He then asserted that the Great Depression was caused by “over-indebtedness to start with and deflation following soon after” (Fisher 1933)—and he was dead right.

So, why didn’t we learn from Fisher, and control private debt? It’s mainly because mainstream economists like Ben Bernanke rejected Fisher’s argument, not because it was wrong, but because it contradicted the Neoclassical model of banking. To quote Bernanke, academic economists ignored Fisher’s analysis:

Because of the counterargument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects. (Bernanke 2000)

As I’ve shown in previous posts, this is a fallacy, because the Neoclassical model of banking is a fallacy. Banks aren’t “mere intermediaries” who enable Savers to lend to borrowers. They are creators of both debt and money. Lending is not a “pure redistribution”, but a creation of new money and spending power. When lending turns negative—which happens when debtors are repaying debt, or going bankrupt and being unable to repay it—the economy crashes. This is what happened in both The Great Depression and The Great Recession.

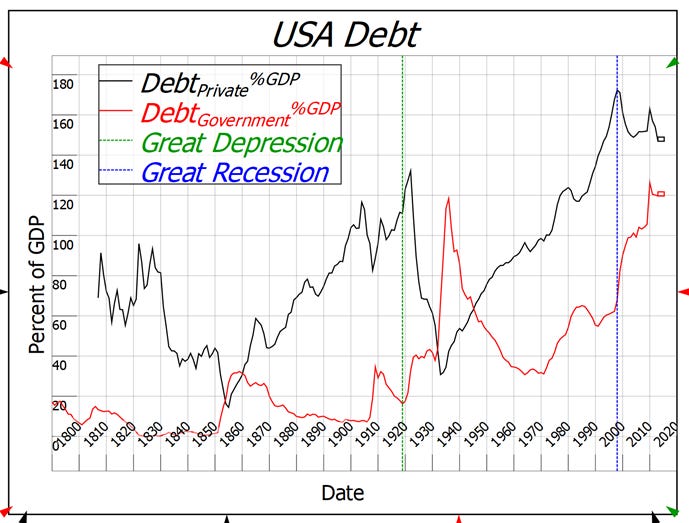

Therefore, thanks to Neoclassical economists, rather than learning from history, we repeated it. Private debt, which had peaked at about 130% of GDP in the early 1930s, fell to just 50% of GDP at the end of World War II. Then it rose, peaked at 170% of GDP, crashed again, and we repeated the experience of the 1930s.

Figure 4: Economists and politicians obsess about government debt, when it’s private debt that matters

I knew that the GFC was going to happen because I built on the work of Hyman Minsky, who in turn built on Fisher to create the “Financial Instability Hypothesis”. Bernanke, on the other hand, ignored Minsky even more than he ignored Fisher.

He got the job as Federal Reserve Chairman because he marketed himself as the expert on The Great Depression. But he wasn’t the expert on The Great Depression itself: instead, he was an expert on explanations of The Great Depression that were consistent with mainstream economic theory.

The only explanation that was consistent with Neoclassical theory was that “the gov’mint did it!”, and that’s precisely what he asserted. In a cringeworthy speech that he gave at Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday party, Bernanke said:

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again. (Bernanke 2002)

Honestly, I could puke! Not only at how obsequious he was, but also because he was so damn wrong about what caused The Great Depression! Hyman Minsky got the cause right when he said that:

the fundamental instability of a capitalist economy is upward. The tendency to transform doing well into a speculative investment boom is the basic instability in a capitalist economy. (Minsky, 1982, p. 66)

And how much attention did Bernanke pay to Hyman Minsky? This is Bernanke’s entire consideration of Minsky in his book Essays on The Great Depression:

Hyman Minsky and Charles Kindleberger have in several places argued for the inherent instability of the financial system, but in doing so have had to depart from the assumption of rational economic behaviour.

[A footnote adds] I do not deny the possible importance of irrationality in economic life; however, it seems that the best research strategy is to push the rationality postulate as far as it will go.

We therefore had someone in control of the Federal Reserve at the time of the Global Financial Crisis, who claimed to be an expert on the Great Depression, but in reality, had no idea of why it happened.

He was equally oblivious to the approach of the Great Recession. In his report to Congress on July 18 2007, Bernanke predicted that growth would be:

“2¼ percent to 2½ percent over the four quarters of 2007 and 2½ percent to 2¾ percent in 2008. The civilian unemployment rate is expected to lie between 4½ percent and 4¾ percent in the fourth quarter of 2007 and to be at about the top of that range in 2008.” (Bernanke, 2007)

The Global Financial Crisis began just three weeks after Bernanke assured Congress that the future was bright. In contrast to his rosy forecasts, growth was zero in 2008—and it fell to minus 4% in 2009—while the unemployment rate at the end of 2008 was 7.8%.

In the aftermath to the crisis that he didn’t see coming, Bernanke borrowed an idea from Richard Werner and Japan: “Quantitative Easing”. Bernanke justified it this way:

The idea behind quantitative easing is to provide banks with substantial excess liquidity in the hope that they will choose to use some part of that liquidity to make loans or buy other assets. Such purchases should in principle both raise asset prices and increase the growth of broad measures of money, which may in turn induce households and businesses to buy nonmoney assets or to spend more on goods and services. (Bernanke, 2009)

This explanation shows how little Bernanke—and Neoclassical economists in general—understand banking.

Firstly, banks can’t lend our reserves: the “Money Multiplier” model is another Neoclassical myth. It’s easy to show, with my Ravel software, that the model only works if all loans are in cash—but that’s a topic for another post.

Secondly, banks can’t buy “other assets”, because one of the few things we learnt from the Great Depression is that it’s a very bad idea to let banks buy shares. One reason The Great Depression was so much worse than The Great Recession was that back then, banks were allowed to buy shares—and when share prices fell 10% in one day, and by almost 90% over the next 3 years, many banks were sent bankrupt. The Glass-Steagall Act banned banks from buying shares, and rightly so.

Today, only nonbank financial institutions—pension funds, insurance companies, vampire squids—can buy shares and property, and bond purchases from them under QE definitely did inflate asset prices.

But the main thing that Bernanke’s statement shows is that mainstream economists are so oblivious to the dangers of private debt that, in the middle of a crisis caused by too much private debt, they thought that encouraging the private sector into yet more debt was a good idea!

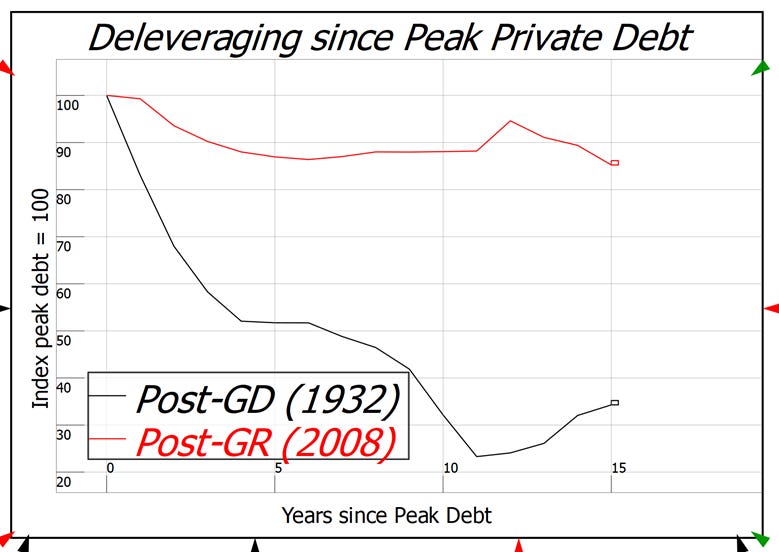

Consequently, the deleveraging after the GFC has been far smaller than what happened after the crash of 1929. Private debt in 1945 was 75% lower than it was when the debt ratio peaked in 1932: it fell from 132% of GDP in 1932 to 34% in 1945. That’s what enabled the “Golden Age of Capitalism” between in the 50s and 60s: low levels of private debt meant that people spent freely, not worrying about having to service their debts.

But since 2007, private debt has fallen by just 15% compared to its peak—see Figure 5.

Figure 5: The Fed has kept private debt much higher than it was after the Great Depression

With private debt higher than its ever been, outside the GFC itself, credit-based demand is stagnant, and so is the economy. At the same time, thanks to The Fed’s support for asset price bubbles, share valuations are ridiculous, and houses are priced out of reach for young people.

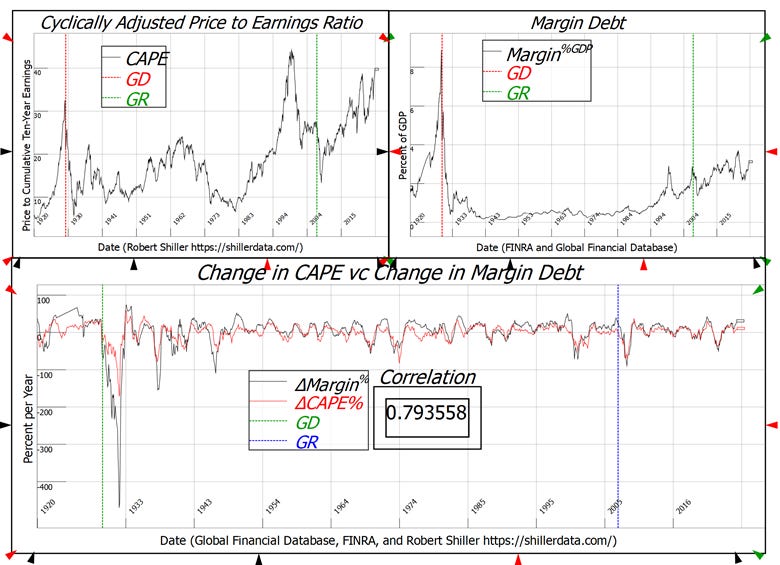

Both have been driven by private debt, as well as by Quantitative Easing. Margin debt is at its highest levels since the Great Depression. Stock market valuations are higher than in 1929, and at their highest level since the Dot Com bust of 2000. This has benefited the wealthy who own shares, and penalized the poor who do not (their holdings via their 401K and the like are trivial).

Figure 6: Change in Margin Debt versus Change in Stock Market Valuations

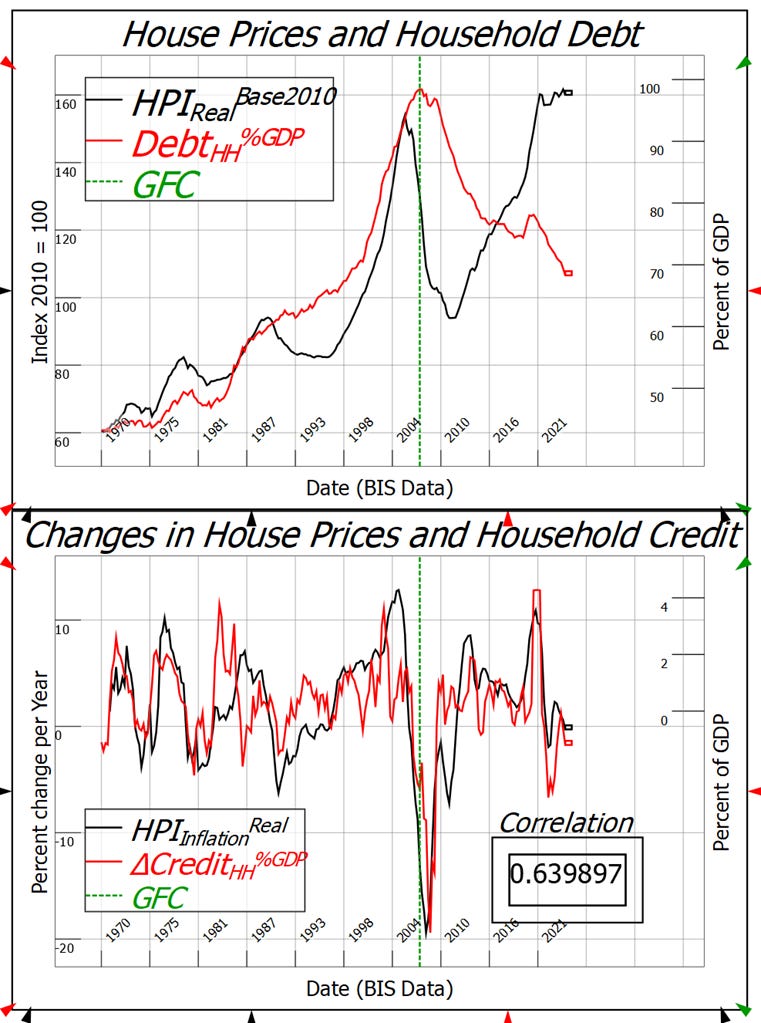

Similarly, the failure to delever after the GFC has meant that house prices, which did fall substantially because of it, have now risen back to a higher level than they reached at the time of the GFC. This again has benefited the wealthy, and penalized the poor.

Figure 7: Change in Household Credit drives House Price Change

If we’re ever going to have a healthy economy again, and affordable housing, we need to reduce the level of private debt, and make sure that any debt issued in future helps the real economy, rather than inflating asset prices. But that gives us a real dilemma: reducing private debt will almost certainly cause asset prices to fall, but the financial situation of many Baby Boomers depends on asset prices remaining high. At the same time, high asset prices lock young people out of buying a home.

How do we thread the needle? Almost two decades ago now, I proposed a solution: a “Modern Debt Jubilee”. Our current crop of politicians will never implement it, but it’s possible that, when the majority of Americans are unable to buy homes, politicians might finally listen to the majority rather than the wealthy.

A Modern Debt Jubilee can’t operate in the same way that ancient debt jubilees did. In ancient societies, private debt turned farmers into debt-slaves, who lost their land and had to work on the land of their creditors. Because only freemen could become soldiers, this in turn meant that those societies were in danger of being conquered by their rivals. So ancient rulers periodically wrote off all household debt, which enabled debt slaves to regain their freedom.

We can’t just write off debt today, for two reasons. Firstly, that could cause a collapse in the money supply, and send the banking system into bankruptcy. Secondly, benefiting just debtors would penalise those people who hadn’t joined into the speculative manias that have given us such overvalued houses and shares.

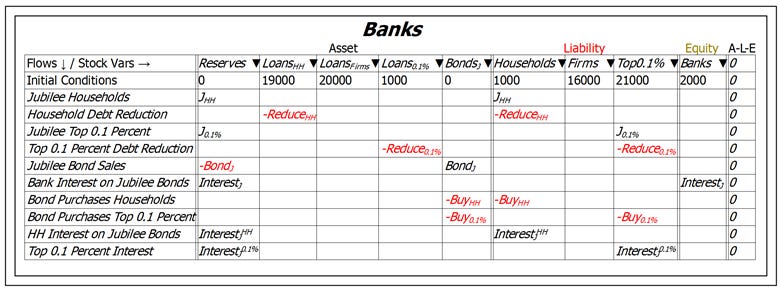

My proposal is to use the capacity of the government to create money to enable households to drastically reduce their debt levels. The government would create the money precisely the same way that it currently finances deficit spending: by going into negative financial equity, which creates identical positive financial equity for the non-government sectors.

The funds would go equally to every working age adult. As a rough guide, there are roughly 200 million Americans, and the USA’s household debt level right now is about $20 trillion. The Jubilee amount could then be $100,000 per person, which would be sufficient to eliminate household debt completely, as the Jubilees of old did.

Those who have any debt at all would be required to pay their debt down. Those without debt would be required to use the funds to buy Jubilee Bonds, which would then give those households an additional source of income.

As well as reducing the level of private debt, this would reverse some of the increase in inequality that has occurred over the last half century, under the flawed economic policies pushed by Neoclassical economists. Because the Jubilee would be a per capita payment the top 0.1% of the population would get 0.1% of the funds, and the bottom 99.9% would get 99.9%. Elon Musk and an unemployed single mother would both get the same amount: $100,000.

There would be no increase in the money supply, because the money created by the Jubilee would be offset by the requirement that the funds had to be used either to pay debt down, or to buy Jubilee Bonds. The Godley Table in Figure 8 shows the basic ideas from the point of view of the banks.

Figure 8: The Banking Sector’s view of a Modern Debt Jubilee

To the extent that this policy caused house prices to fall, home owners would be compensated by the decrease in their debts. And this would happen without having to sell the house: at the moment, when people claim that their house is worth, say, $1 million, they have to sell it to actually realize the money. With this scheme, they get $100,000 now, without having to sell.

In a later post, I’ll simulate this model to show how a Modern Debt Jubilee could reverse most of the policy mistakes made by Neoclassical economists, thanks to their failure to understand the monetary system. In the meantime, please share this post around.

Be the first to comment