A look at the history of political economy

Steve Keen is an Australian economist and author. A post-Keynesian, he criticizes neoclassical economics as inconsistent, unscientific and empirically unsupported.

Cross-posted from Steve Keen’s Building a New Economics

I was asked to contribute to the 95th edition of the Journal of Australian Political Economy to celebrate 50 years of the Department of Political Economy at Sydney University, since I was one of the key students whose protests in 1973 motivated the Department’s formation. This is my draft paper. I’ll make it publicly available after the special issue comes out, probably in mid-2025.

As an active participant in the events that led to the formation of the Department of Political Economy at Sydney University in 1975, and as someone whose life was transformed by those events, I am delighted to contribute to JAPE 95 on the Department’s 50th anniversary. Looking back after more than a half-century’s life experience in economics, I now appreciate how unique and important those events were.

By the time the Political Economy dispute erupted in 1973, there had been sufficient intellectual progress in economics to justify the overthrow of the Neoclassical paradigm. It persisted, not because it was correct, but because its adherents were intransigent, and because its pseudo-scientific mumbo-jumbo supported the capitalist ruling class, even though it was wildly wrong about the actual nature of capitalism. It remains undead today for the same reasons.

Veblen’s attack on Neoclassical economics as “a taxonomic science”, rather than an evolutionary one, in “Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science?”, was published in 1898 (Veblen 1898, p. 389), contemporaneously with Marshall’s declaration that evolution, and not equilibrium, was the preferred analytic framework for economics:

in the later stages of economics, when we are approaching nearly to the conditions of life, biological analogies are to be preferred to mechanical … The Mecca of the economist is economic biology rather than economic dynamics. (Marshall 1898, p. 43)

And yet the equilibrium fetish of the Neoclassical school has only gotten more extreme with time.

Sraffa’s logical critique of Marshall’s fallacious theory of the firm occurred in the 1920s (Sraffa 1926), and was followed by decades of empirical research which established that real-world firms do not experience rising marginal cost as Neoclassical theory assumes, but constant or even falling marginal cost (Besomi 1998; Lee 1981; Wilson and Andrews 1951; Blinder 1998).

And yet the fiction of rising marginal cost still reigns supreme today, not only in microeconomics, but even in “micro-founded” macroeconomics.

Gorman (Gorman 1953) and Samuelson (Samuelson 1956) committed classic “own-goals” in the 1950s, when they inadvertently proved that a market demand curve could be guaranteed to slope down in price like an individual demand curve if, and only if, both “all men” and all commodities were identical:

The necessary and sufficient condition quoted above is intuitively reasonable. It says, in effect, that an extra unit of purchasing power should be spent in the same way no matter to whom it is given. (Gorman 1953, p. 64, p. 64. Emphasis added)

The common sense of this impossibility theorem is easy to grasp. Allocating the same totals differently among people must in general change the resulting equilibrium price ratio. The only exception where tastes are identical, not only for all men, but also for all men when they are rich or poor. (Samuelson 1956, p. 5. Emphasis added)

And yet economics textbooks still teach students that downward-sloping market demand curves can be derived from downward-sloping individual demand curves—though Mas-Colell’s PhD textbook does at least caution that this conclusion requires the existence of “a benevolent central authority” which “redistributes wealth in order to maximize social welfare” (Mas-Colell et al. 1996, p. 117) before market trades occur!

Sraffa’s proof that the distribution of income had to be based upon relative bargaining power, rather than “marginal productivity” (Sraffa 1960), led to the Capital Controversies (Pasinetti et al. 2003) in the 1960s, in which no less a Neoclassical than Paul Samuelson ultimately conceded defeat:

Pathology illuminates healthy physiology. Pasinetti, Morishima, Bruno-Burmeister-Sheshinski, Garegnani merit our gratitude for demonstrating that reswitching is a logical possibility in any technology …

There often turns out to be no unambiguous way of characterizing different processes as more “capital-intensive,” more “mechanized,” more “roundabout,” except in the ex post tautological sense…

If all this causes headaches for those nostalgic for the old time parables of neoclassical writing, we must remind ourselves that scholars are not born to live an easy existence. We must respect, and appraise, the facts of life. (Samuelson 1966, pp. 582-3. Emphasis added)

And yet economics textbooks—including Samuelson’s—continued to teach the myth of marginal productivity as the basis of income distribution.

There were, therefore, enormous currents of justified criticism of mainstream Neoclassical economics in general, and of the teaching of it in particular, before the dispute at Sydney University began.

Its genesis can be traced to 1968, when a Neoclassical economist—Bruce Williams—became Vice-Chancellor at Sydney University, and then promptly appointed two other Neoclassical economists—Colin Simkin and Warren Hogan—as Professors to deform (not a typo) the department away from its humanist and Keynesian foundations.

I’ll let others who were there at the time recount the pre-1971 history. But one under-appreciated aspect of that history, I feel, is the positive contribution that those Professors made to the revolt in 1973. The authoritarian manner in which an extreme and mendacious Neoclassical curriculum was imposed on an, until then, relatively harmonious and democratically managed Department, led to numerous staff (and students) being disgruntled and eager for change.

The student component of the Political Economy struggle owes its primary thanks to Professor Colin Simkin. Simkin was the main designer of the course structure that he and Hogan imposed on the Department, and it was boring, in both structure and content. All of first year was devoted to Micro, Macro was the only topic for 2nd year, and International occupied all of 3rd year—relieved, partially, by Ted Wheelwright’s brilliant lectures on the history of economic thought. Ted effectively summarised the student reaction to this Neoclassical curriculum with his quip about Neoclassical economists “tobogganing up and down their indifference curves until they disappear up their own abscissas”. Even the staunchly Neoclassical Neil Conn concluded his lectures in the first term of 1971 by declaring that we had covered the topic of Neoclassical demand theory “in excruciating detail”—minus, of course, the details about its false assumptions and logical fallacies noted above.

Secondly, Simkin gave the core Macro lectures, and he was a dreadful lecturer—so much so that we used to invite friends from other disciplines to attend, to experience just how bad he was firsthand. This culminated in Simkin walking out of his own lecture in mid-1972, because it was obvious, from the deafening hubbub in the lecture hall, that no-one was listening to him.

Thirdly, he set his own book Economics at Large (Simkin 1968) as the textbook for the course. The best things about Economics at Large were its title and its cover, after which things went seriously downhill. Not only was its prose turgid, the book’s numerous equations had numerous mathematical errors, which led to Simkin starting each lecture with errata to his own book. His “walkout” lecture commenced with me asking him, from the front row of Merewether 2, to produce an errata booklet to save us the trouble of amending his text every lecture. He declined, and invited me to do it myself. At the moment that he staged his Professorial walkout, a medical student friend of mine was doodling daisies on my shoulder to relieve the boredom.

Figure 1: Simkin’s dreadful macroeconomics textbook

When the Political Economy Movement lost its connection with students somewhat in the later 1970s, one activist (from memory, Bruce Lanahan) noted how radicalising an experience it was to be lectured by Simkin. By saving Political Economy students from that fate, we denied them a taste of what had motivated the creation of Political Economy in the first place.

Hogan fancied himself as a future Vice-Chancellor. He later lamented that he would have achieved his ambition, had it not been for the student protests. His attempts to negotiate a settlement with student activists, while simultaneously refusing to change the curriculum, ended up turbo-charging the revolt.

When students laughed at one of Hogan’s comments at a “town hall” meeting he chaired in the Professorial Board Room, Hogan commented that “You’re welcome to laugh at that, it’s your privilege”. One until-then uncommitted Honours student exclaimed that “It seems to be the only one we’ve got”. Hogan’s challenge that “if you think you can design a better course, go ahead” led to us doing precisely that, and drafting what became the first-year unit in Political Economy in 1975.

Williams supported his chosen Professors at every step, but in the post-Vietnam War days of 1973, this was merely waving a red rag to a bull. Students who had been protesting The War and The Draft until the end of 1972, and who now faced neither conscription nor fees, thanks to their abolition by Whitlam— and who also enjoyed unheard-of employment prospects at the time, with unemployment falling from 2.6% to 2.1% over the course of 1973—turned their energies to reforming their education. Williams’ support for the Professors had the opposite effect to what he intended.

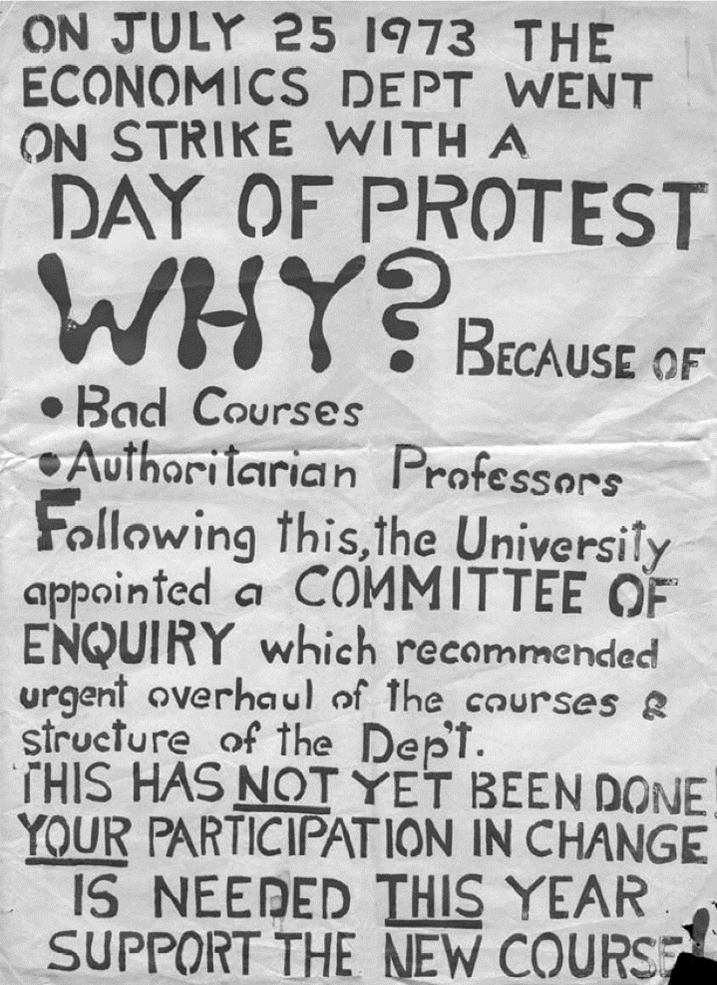

The revolt, which began with a “Day of Protest” on July 25th 1973, was the first ever revolt by economics students against Neoclassical economics anywhere on the planet.

Figure 2: Kevin McAndrew’s 1975 poster celebtrating the Day of Protest in 1973

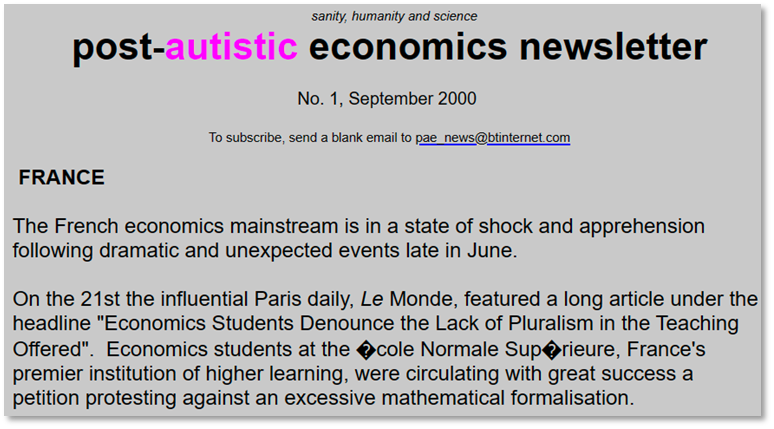

Nothing like it happened again for over 25 years, until French students created the Protest Against Autistic Economics (PAECON) in September 2000.

Figure 3: The manifesto of the students who established the Post-Austistic Economics Society in France in 2000

The next comparable event was the walkout by students from Gregory Mankiw’s first year economics lectures at Harvard in 2011. Another year passed before students at Manchester University formed the Post-Crash Economics Society to revolt against their Neoclassical curriculum in the aftermath to the Global Financial Crisis.

Figure 4: The establishment of the Post-crash Economics Society in Manchester in 2012.

All these protests had the same motivation. To quote from the first issue of the Post-Autistic Economics Newsletter, the French protesters called for “an end to the hegemony of neoclassical theory and approaches derived from it, in favour of a pluralism that will include other approaches, especially those which permit the consideration of “concrete realities”.”

Each of these protests was successful in the short-term.

Our original protest at Sydney University led to the formation of the Department of Political Economy, whose 50th anniversary we celebrate in this special issue of JAPE. The French students’ protest gave birth to the Real-World Economics Review, which is still going two decades later. The Manchester protests led to the formation of Rethinking Economics, which supports students around the world who are dissatisfied with the state of economics today. The Harvard walkout played a role in the establishment of INET’s Young Scholars’ Initiative. These successes have kept the challenge to Neoclassical economics alive, long after the protests which gave birth to them ended.

Unfortunately however, more than 50 years after our protest, that same Neoclassical hegemony is alive and well—or at least undead. The pedagogy and paradigm that we railed against in the 1970s has evolved into something even more absurd and anti-realistic than the absurd and anti-realistic dogmas we protested against in 1973 (Krueger 1991). So, since the objective of our protests was to replace the fantasies of Neoclassical economics with a realistic approach to economics, they have, in this sense, failed.

Figure 5: The Political Economy Society protests in the Main Quadrangle in 1975. Staff members John Burgess and Paul Roberts stand with them.

Of course, we didn’t know that we would fail, back in July 1973, when 300+ students enthusiastically responded to Richard Osborne’s proposal to hold a “Day of Protest” against the boring and delusional theories we were being fed. Instead, we experienced the thrill of openly challenging our Professors, giving alternative lectures on the actual day, marching, chanting, waving banners, partying, and, in subsequent years, occasionally occupying the Vice-Chancellor’s office and the Merewether staff room.

Figure 6: The occupation of the Vice-Chancellor’s office in 1975.

It was an exciting and life-changing experience for us all—for me more than most, since I devoted the rest of my life to continuing the rebellion we started in 1973. The buzz of optimistic rebellion is hard to explain to today’s harassed students, flitting between one part-time job and another as they try to pay their student debts. In 1973, it felt like real change was possible.

What do we want?

Political Economy!

When do we want it?

Now!

Figure 7: Mike Brezniak, who sadly took his own life a few years later, addresses a protest in the Main Quadrangle in 1974

But what have we got, 50 years later? Political economy has continued on, but the mainstream is as ascendant as ever—despite its numerous failings at the time and since.

I had hoped, in those subsequent years, that a clear failure by Neoclassical economics would help expose it for the fraud it is. I thought that the failure to realise, in the Noughties, that a serious economic crisis was imminent (Keen 2006, 1995, 2020b), would permanently tarnish the status of conventional economics. Not only did Neoclassicals not realise that a crisis was imminent, they actually thought that they had eliminated the very possibility of crises.

Janet Yellen spoke at the annual Hyman Minsky Conference at Bard College in 1996, and declared that “The ‘New’ Science of Credit Risk Management at Financial Institutions” made another Great Crash like that in 1929 an impossibility, let alone a repeat of the Great Depression. Thirteen year later she admitted her mistake at the same venue (Yellen 2009). But despite this, another 15 years later, she still supports the same policies that preceded the crash of 2007.

Speaking as the incoming President of the American Economic Association, Robert Lucas—one of the fountainheads of modern Neoclassical macroeconomics—made the following bold and utterly false statement in his Presidential lecture at the end of 2002:

Macroeconomics was born as a distinct field in the 1940’s, as a part, of the intellectual response to the Great Depression. The term then referred to the body of knowledge and expertise that we hoped would prevent the recurrence of that economic disaster. My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. (Lucas 2003, p. 1. Emphasis added)

Two decades later, despite the failure of Neoclassical “Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium” models to anticipate the biggest economic crisis since the Great Depression, and despite Nobel Laureates like Paul Romer and Joseph Stiglitz rubbishing them, DSGE models are still the workhorses of Neoclassical economics.

Figure 8: Paul Romer, who received the “Nobel” Prize in Economics in 2018, justly rubbished Neoclassical macroeconomics in 2016

Today’s students are still required to learn these arcane and misleading models, as if the crisis they failed to anticipate did not occur.

Figure 9: Joe Siglitz, another “Nobel” winner, did likewise in 2018

Why has Neoclassical economics persisted, despite its many failures? Mainly because, as Max Planck put it, a real science overthrows a false paradigm, not by persuading existing believers to change their minds, but by generational change:

It is one of the most painful experiences of my entire scientific life that I have but seldom—in fact, I might say, never—succeeded in gaining universal recognition for a new result, the truth of which I could demonstrate by a conclusive, albeit only theoretical proof… A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it. (Planck 1949, pp. 22-4. Emphasis added)

Generational change occurs in sciences because, once an anomaly is discovered that contradicts a key prediction of the dominant paradigm, the anomaly exists forever. Once the Michelson-Morely experiment disproved the theory of the “aether”—a substance that, according to the Maxwellian theory of electromagnetics, was supposed to fill a vacuum to enable light waves to be transmitted through it—then students could replicate the anomaly for themselves. With a new paradigm in the making, but with Professors teaching the old one despite its failure, science students would be almost unanimous in their opposition to what they were being taught. But rather than striking against their education, as we did, all they had to do was wait. When it came to replacing the professors, when they retired or died, the only candidates were top students who accepted the new paradigm and rejected the old.

Unfortunately, in economics, anomalies are historical and transient, rather than eternal and reproducible. The Great Depression, WWII, the post-War “Golden Age of Capitalism”, the 70s Stagflation, the 80s stock market bubble, the 90s recession, the Great Recession, now the post(?)-Covid boom and inflation… Each new crisis knocked the previous one off its pedestal. The fact that Neoclassical economics can’t explain the Great Depression—or that it has an explanation which is an insult to anyone who lived through it (Prescott 1999)—doesn’t matter to any modern economist who is working today’s issue of inflation. Old failures can be forgotten.

Just as importantly, the underlying Neoclassical vision of capitalism is a highly seductive one. It is a meritocracy in which what you earn is what you deserve, where harmony rules because of equilibrium, and which is free of coercion: there’s no need for government control when the market works “perfectly”. Therefore, even if some students break away from Neoclassical economics because of one of its failures, enough “true believers” can be found in the student body to replace existing “true believers” when they retire.

I spent my late teens fighting against believers in Neoclassical economics who were then two to three times my age—and though I challenged them vigorously, part of me felt that, being older and more experienced, they must know more than I did. Now in my seventies, I am still fighting believers in Neoclassical economics who range from being my contemporaries (Paul Krugman is one month older than me) to being one third of my age. I know they know less than I do, not only about economics in general, but even about their own school of thought. But they teach at Harvard and Cambridge, while I and fellow critics labour at lowly ranked universities with excessive teaching burdens and fragile finances.

Funerals, therefore, aren’t sufficient to cause a true scientific revolution in economics. The generational change that enables new paradigms to emerge in sciences does not occur in economics.

The final factor that enables economics to escape the revolutionary change it desperately needs is rather ironic: myths in economics survive because, despite the dominance of our politics by economic ideas, you don’t need economic theory or economists to have an economy. The economy exists independently of economists, and would probably function a lot better if economists simply didn’t exist. In contrast, engineering doesn’t exist independently of engineers: you need engineers to create the technological marvels the rest of us take for granted, and when something goes wrong with the things that engineers create, engineers face real consequences: a collapsing bridge fingers the engineers who didn’t take account of its harmonics, a crashing plane implicates the engineers (or their managers) who approved a faulty design.

To use Nicholas Taleb’s phrase, economists don’t have any “skin in the game”: they don’t suffer any serious consequences when their advice is badly wrong, and there is a myriad of complicating factors that they can point at to explain away any failure. Ironically, the fact that economists aren’t strictly necessary is something that gives them great power. They are the witchdoctors of capitalism, holding the leaders of our society in their thrall as they read the entrails of their Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium models, while at the same time they have no idea how that society actually works.

So, do I regret organizing The Day of Protest, half a century ago? Or being one of those to occupy the Vice-Chancellor’s office in 1975? Not a bit of it.

Figure 10: The Political Economy Movement had the support of journalists and editorial writers in the 1979s.

Firstly, though our protest failed to dislodge the mainstream, we were as right about Neoclassical economics being a false paradigm as Galileo was about the Ptolemaic model of the universe—and these days I’ve taken to referring to Neoclassical economics as Ptolemaic Economics, to highlight that point. One should never regret fighting for truth and against fallacy.

Secondly, it was rewarding hard work. The 50 or so of us who put The Day of Protest together had never worked so hard in our lives before, and possibly since, and we worked for passion and a commitment to truth, rather than for money. Richard Osborne first proposed the idea, and became a pivotal part of our negotiating team; Greg Crough, Richard Fields, Graham Kerridge and I initiated the revolt, planned the Day of Protest, and gave several of the alternative lectures on the day; Bill Nichols responded to the need for banners by producing two 25-metre-long calico banners and numerous smaller ones; Kevin McAndrew churned out posters like an automaton.

Thirdly, I saw real courage in action. Several of the staff publicly sided with the students: Paul Roberts, Jock Collins, and above all, Frank Stilwell, put their careers on the line by speaking out in our favour, literally in full view of the Professors, on the Day of Protest itself: Hogan and Simkin could be see watching the speeches in the Quadrangle of the Merewether Building, from the window of Hogan’s office. Margaret Powers and Geelum Simson-Lee assisted us within the confines of the University’s administrative system, especially with Geelum’s decision that the vote on whether the Faculty should investigate the Economics Department would be a secret ballot (it was passed, 24 votes to 14).

Other staff, including John Burgess, Evan Jones, and Gavan Butler, galvanised us. At a chance meeting in the vestibule to the Merewether Building, Gavan implored me to begin student action the week before the Day of Protest. When I initially rejected his request on the basis that Economics students were too apathetic, he replied that Frank’s first year class had voted to support the Philosophy Strike. That exciting news set off the events that led to the Day of Protest itself. Other departments—including Accounting and Politics (then called Government) surreptitiously assisted us with printing facilities—and even proof-reading our leaflets!—and their staff voted with us in the Faculty motion to investigate the Department of Economics.

Fourthly, it was great, great fun. Hundreds of students attended the alternative lectures we put on, and most stayed for the mother of all parties that finished the evening.

Figure 11: This “ring around the burning Professorial effigy” preceded the occupation of Wiliams’s office in 1975

Finally, Political Economy pointed the right way forward, when the world was about to embark on a Neoliberal journey in the opposite direction. We didn’t realise it then, but our rebellion in 1973 was the counterpoint to the ascendancy of Neoclassical economics in the world of policy. At the same time that we were trying to pull it down, politicians, administrators and journalists around the world were succumbing to the fantasies of Neoclassical economics. The stagnant and crisis-ridden decades that followed showed the gap between its promises and the impact of imposing its false beliefs on the real world.

If I had done nothing else of significance in the following 50 years, I could still look back on The Day of Protest with great pride and pleasure. So, from my 72-year-old self in 2025, to the 20-year old rebel in 1973, here’s lookin’ at you, kid. And here’s to today’s rebel Political Economists as well.

Figure 12: Me in 1973, just months before the Day of Protest, and in 2024

“The ruthless criticism of the existing order”

If we have no business with the construction of the future or with organizing it for all time, there can still be no doubt about the task confronting us at present: the ruthless criticism of the existing order, ruthless in that it will shrink neither from its own discoveries, nor from conflict with the powers that be. (Marx 1843)

I would be remiss if I did not note my major criticism of Political Economy as actually practised at Sydney University: its failure to use mathematics both as a weapon against Neoclassical economics, and as a way to help construct a new economics.

Neoclassical economists do not use mathematics: they abuse it. I coined the neologism “mythematics” to describe what they do, and my colleague Asad Zaman coined the equally apt “mathemagics”. What Neoclassicals do appears to be mathematics to the uninitiated, but they either use the wrong mathematical tools, or start from ludicrous assumptions, or make even more ludicrous assumptions when the results they reach don’t have the properties they desire.

This was evident to the engineer Jay Forrester when he first encountered Neoclassical economics. His reflections on the sorry state of mathematical analysis by economists in the mid-1950s is, if anything, even more true of today’s Neoclassical diehards:

Note to the Faculty Research Seminar. From: Jay W. Forrester. November 5, 1956

During the last three months I have read a small part of the literature on economic models … considering it from the viewpoint of one who is new to the field…

Present models neglect to interrelate adequately the flows of goods, money, information, and labor…

Linear equations have usually been used to describe a system whose essential characteristic, I believe, arise from its non-linearities…

Many models are formulated in terms of systems of simultaneous algebraic equations. These impress me as particularly unsuited to the kind of behavior being studied…

Very often the model and its results are judged by the logic with which the model is developed out of its founding assumptions, whereas the failures probably lie in those assumptions. (Forrester 2003, pp. 329-335)

The experience inspired Forrester to begin the development of system dynamics—a method to develop truly dynamic models using flowcharts, which replaced the Neoclassical “ceteris paribus” with the real-world of “everything depends on everything else” (Andersen et al. 2007). These techniques lead to radically different mathematical models of the economy than the “mythemagic” nonsense peddled by Neoclassicals. Neoclassicals insist on deriving macroeconomic analysis from microeconomic concepts, not because this is the right thing to do, but because they can’t think of any other way to proceed:

The pursuit of a widely accepted analytical macroeconomic core, in which to locate discussions and extensions, may be a pipe dream, but it is a dream surely worth pursuing. If so, the three main modeling choices of DSGEs are the right ones. Starting from explicit microfoundations is clearly essential; where else to start from? (Blanchard 2016, p. 3. Emphasis added)

In fact, physicists realised almost fifty years earlier that it is not, in general, possible to derive a higher level of analysis (such as macroeconomics) from a lower level one (such as microeconomics). As the genuine Nobel Laureate, physicist P.W. Anderson, put it:

The main fallacy in this kind of thinking is that the reductionist hypothesis does not by any means imply a “constructionist” one: The ability to reduce everything to simple fundamental laws does not imply the ability to start from those laws and reconstruct the universe… at each level of complexity entirely new properties appear, and the understanding of the new behaviors requires research which I think is as fundamental in its nature as any other… Psychology is not applied biology, nor is biology applied chemistry (Anderson 1972, p. 393. Emphasis added)

And nor is macroeconomics “applied microeconomics”. Instead, as I showed in “Emergent Macroeconomics: Deriving Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis Directly from Macroeconomic Definitions” (Keen 2020b) and The New Economics: A Manifesto (Keen 2021), macroeconomics can be derived directly from indisputable macroeconomic definitions.

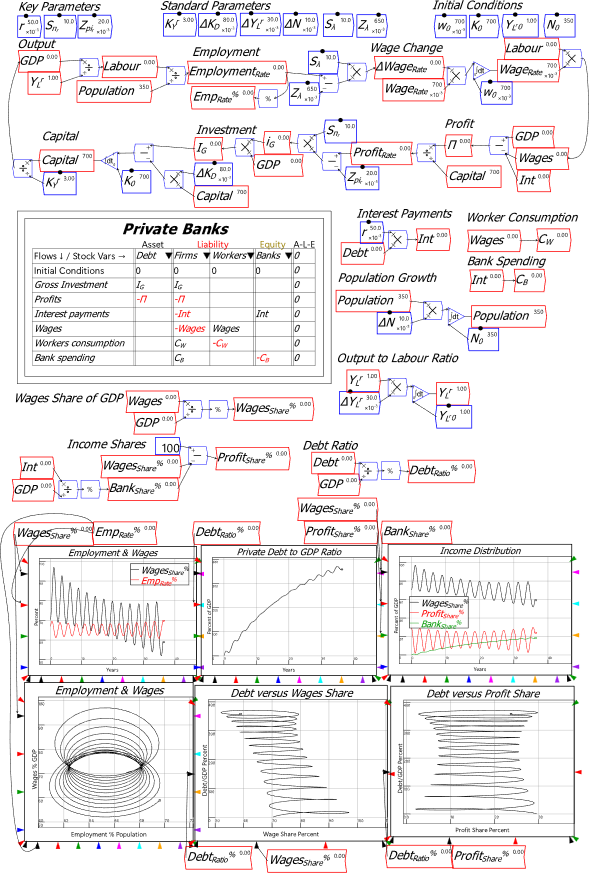

The macroeconomics that results is anti-Neoclassical. Dynamize the definition of the employment rate and the wages share of GDP and, with reasonable simplifying assumptions—that workers’ wage bargaining power is high when the employment rate is high, and that capitalists invest their profits—you get Goodwin’s “growth cycle” model (Goodwin 1967; Goodwin 1966), which itself was inspired by Marx’s verbal model of a cyclical economy in Volume I of Capital (Marx 1867, Chapter 25, Section 1). Add the existence of a banking sector that creates money when it lends (Moore 1979), and replace the assumption that capitalists invest all their profits with the more realistic assumption that capitalists invest more than profits during a boom, and less than profits during a slump, and you get Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis” (Minsky 1982)—see Figure 13. Include government deficit spending and you get a complex-systems version of Modern Monetary Theory (Kelton 2020).

The system dynamics approach can be applied not only to macroeconomics but to the many other social and economic issues that the Department of Political Economy explores (Zaini et al. 2017; Mallick et al. 2014; Radzicki, Tauheed, and Hayden 2009; Pavlov, Radzicki, and Saeed 2005; Radzicki 2003, 1988).

What’s more, these models can be derived using the flowchart logic pioneered by Jay Forrester. The relatively simple model shown in Figure 13 is far more insightful about the nature of capitalism and its potential for crises than anything a student of Neoclassical economics will ever learn.

Figure 13: Minsky’s “Financial Instability Hypothesis” derived from macroeconomic definitions and modelled as a flowchart process in the Ravel software I developed—see https://www.patreon.com/ravelation.

The Next 50 Years?

Fifty years of experience with academic economics has taught me that real change in economics will not come from conventional economics departments. Neoclassicals have driven critical economists out of all the leading Universities, which pushed my colleagues and I into low-ranking Universities where we were at the mercy of government policy changes that were often motivated by Neoclassical thinking. The progressive curriculum that I helped develop at the then University of Western Sydney was terminated largely because of the removal of first year quotas. I built a strong heterodox program at Kingston University in London, only to see that undermined when the UK government copied the Australian government’s market-oriented deform a year or so later. Today, despite significant student interest in alternatives to Neoclassical economics, only a handful of universities around the world offer a non-Neoclassical curriculum.

A major factor behind this decline of heterodox economics, at a time when it should be rising, is the determination of Neoclassical economists at leading universities to drive out heterodox thinkers. This process has turned even Cambridge UK into a mainstream stronghold, when it used to be a bastion of critical thought in economics. The only critical economists left at Cambridge—Ha-Joon Chang (Chang 2010) and Tony Lawson (Lawson 2013)—teach in non-Economics departments.

In this sense, the survival of Political Economy is vital to the continuing development of alternative paradigms that could supplant Neoclassical economics. You have no Neoclassical economists on staff, nor are any likely to apply—let alone get appointed. You are therefore, to some extent, insulated from the Neoliberal rot that undermines heterodox economists working in mainstream economics departments. You can therefore do what we tried to do. I would be delighted to see the Department of Political Economy exploit that advantage by appointing staff who can teach and develop the system dynamics approach to political economy.

There remains the question of whether society in general, let alone the Political Economy Department, will survive another 50 years. In 2019, I discovered to my horror that a major reason why humanity has done so little to prevent climate change is because Neoclassical economists have simply assumed that it won’t be a problem (Keen 2023; Keen et al. 2022; Lenton et al. 2021; Keen 2020a). William Nordhaus reached the conclusion that 3°C of global warming by 2100 will reduce global GDP in 2100 by a mere 3.1% (Barrage and Nordhaus 2024, p. 3) by, inter alia, assuming that a roof will protect you from climate change (Nordhaus 1991, p. 930: “Our estimate is that about 87 % … of United States national output … is produced … in sectors that are negligibly affected by climate change”).

This delusional nonsense suited the agenda of fossil fuel companies. They have led and financed the war against action, and Neoclassical economists have supplied them with the ammunition to fight that war. They have won in the court of public opinion, as we can see from the election of climate-change-denying leaders across the planet. But they will not win against Nature. The crazy climatic events we are now regularly seeing across the globe could herald the collapse of human civilisation itself. Though they will doubtless claim that all would have been good had we only followed their recommendations for carbon pricing, the reality is that Neoclassical economists have encouraged complacency in the face of the biggest threat that human civilisation has ever faced.

In this sense, the Political Economy struggle is far bigger than any of us realised, way back in 1975. We are fighting, not merely for more realistic economic theory, but for the survival of human civilisation itself.

Keep on fighting.

Steve Keen

“Donate to enable BRAVE NEW EUROPE continue providing realistic analyses of critical issues. Analysts like Ann Pettifor, Michael Hudson & I rarely get into mainstream media. BNE is our voice. I just donated” https://braveneweurope.com/donate

Please give what you can

Be the first to comment