Would market volatility amidst global trade tensions and uncertainty cause a global recession? Although the world’s major central banks had managed to avoid risks in the first week of June, despite some small variations at some maturities, the United States yield curve remained more or less as it was at the beginning. What will happen in the not-so-distant future?

T Sabri Öncü (sabri.oncu@gmail.com) is an economist based in İstanbul, Turkey.

This article first appeared in the Indian journal Economic and Political Weekly on 7 June 2019.

The titles of a few recent articles give some idea about what has been going on in the bond market lately: “The Bond Market Is Giving Ominous Warnings about the Global Economy” (Irwin 2019), “History Tells Us Why the Fed Should Take the Inverted Yield Curve Seriously” (Coppola 2019), “Donald Trump’s Beautiful Economy is Now on Full Recession Alert” (Evans-Pritchard 2019), and “Investors Could Tip the US Economy against Themselves: There’s Risk for a Self-fulfilling Cycle of Market Instability and Economic Disruptions” (El-Erian 2019).

It is likely that Friday, 31 May 2019 will be considered to be one of the milestones of the ongoing global financial crisis that started in the summer of 2007. It is because, in a sequence of two tweets on Twitter, President of the United States (US) Donald Trump declared that 5% tariffs would be imposed on all goods coming into the US from Mexico, until the time the inflow of illegal Mexican migrants stopped. This, as the ongoing US–China trade war that started early in 2018 had already escalated in May 2019.

On the same day, although there was no mention of the “r-word,” JP Morgan economist Michael Feroli said that he expected the US central bank, the Federal Reserve (Fed), to lower key lending rates two times later this year: one quarter-point cut in September, followed by another quarter-point cut in December. And on the same day, citing the same expectation because of growing risks to the economy from trade tensions, JP Morgan analysts revised down their year-end targets on 2-year Treasury yields to 1.40% from 2.25% and on 10-year Treasury yields to 1.75% from 2.45%.

On Sunday, 2 June 2019, President Trump summarised the current state of the trade war in a sequence of three tweets. Also, on 2 June 2019, Morgan Stanley released a research note in which its chief economist Chetan Ahya argued that a recession could begin in nine months if President Trump pushes to impose 25% tariffs on an additional $300 billion of Chinese exports and China retaliates with its own counter-measures. He wrote: “With the latest developments suggesting that trade escalation is still in play, the impact of trade tensions on the global cycle should not be underestimated.”

Recall that only three months ago (Öncü 2019), while many had been admitting the possibility of a global slowdown, there had been a near consensus that a global recession was nowhere near the horizon. So the Morgan Stanley research note was a major change of mind by a major global financial player.

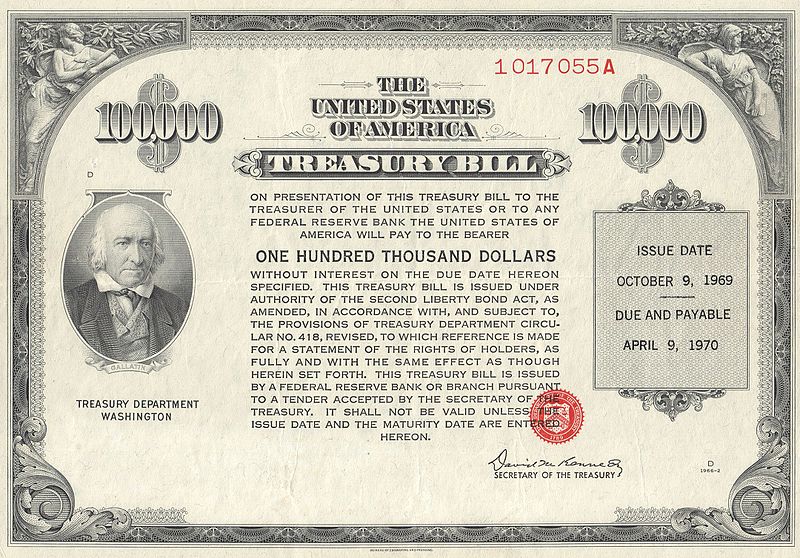

The Bond Market

As Pedro Nicolaci da Costa, director of communications at the Economic Policy Institute, noted, while daily gyrations in the equities steal the headlines, bonds are Wall Street’s sleeping giant. He wrote and I agree: “What happens with Treasury notes is often a more relevant indicator of broader economic trends” (da Costa 2019).

On 22 March 2019, the spread between the 10-year and 3-month Treasury yield (10y–3m spread) went negative for the first time since the last US recession that ended in June 2009. It remained negative until 26 March 2016 after which it became positive and remained positive until 22 May 2019. The significance of this is that since World War II, every time a recession occurred in the US, the 10y–3m spread went negative shortly (usually 6–12 months) before the recession started, although the reverse has not been the case always.

When this spread goes negative, most people call the yield curve inverted. But, this would be correct only if the yield curve is a straight line so that any arbitrarily selected points on it would give us the same slope. However, the slope of any non-straight curve changes from point to point so that while a section of the curve may be inverted, another section may be upward sloping. Since the yield curve is hardly ever a straight line, the 10y–3m spread is not the only possible measure of the yield curve slope. Another popular measure is the 10y–2y spread and there are several others.

The significance of the 10y–3m spread, in its academic popularity goes back to the paper by Estrella and Mishkin (1996). In this and later papers, they documented a strong predictive power of this particular term spread for recessions and economic activity. Later, similar measures had been employed for other advanced capitalist countries, such as Germany, United Kingdom (UK), Canada and the like, and similar relationships between yield curve inversions and recessions have been found. And, unfortunately, many of the yield curves are inverted around the world these days.

The Euro area, the UK, Switzerland and Canada all have inverted yield curves at shorter maturities. Hong Kong’s yield curve is inverted along almost its full length. Japan and South Korea have flat yield curves that could invert at any time. (Coppola 2019)

Of course, it goes without saying that whether such local inversions always lead to local recessions and such collective inversions always lead to global recessions has always been debatable. Naturally, many has dismissed the yield curves’ predictive ability of recessions, but history is filled with the examples of those who lost their shirts after ignoring the yield curves’ warnings, at least, in advanced capitalist countries.

Black Monday?

Although the 10y–3m spread went negative for the second time on 22 May 2019 and widened on 29 May 2019 to its deepest level of about -10 basis points since the onset of the global financial crisis in the summer of 2007, the real damage occurred on Monday, 3 June 2019, after the events described earlier. At one point on 3 June, the 10-year yield went down to 2.067% from 2.5% at the beginning of May and the 10y–3m spread was about -28 basis points. Although this was not as large a spread as the ones witnessed in the summer of 2007, it was sizeable to say the least.

Another notable event occurred in the Eurodollar futures market. Eurodollar futures prices reflect market expectations for interest rates on 3-month Eurodollar deposits for specific dates in the future. The final settlement price of Eurodollar futures is determined by the 3-month London Inter-bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) on the last trading day. On 3 June, the spread between the June 2019 and June 2020 Eurodollar futures contract reached an astonishing -79 basis points (also a type of inversion), unseen and even larger than the comparable spreads in the summer of 2007.

However, despite all these, and given that nothing significant happened to the equities, although the technology index NASDAQ dropped 1,61% after reports that the US antitrust officials were preparing to investigate companies such as Apple, Facebook and Alphabet, the broad market index S&P500 dropped only by 0.3%.

Therefore, 3 June 2019 was not a Black Monday as we had learned during the rest of the week; at least, for the time being.

On the morning of Tuesday, 4 June 2019, at a Fed research meeting in Chicago, the Fed Chairperson Jerome Powell said:

I would first like to say a few words regarding trade negotiations and other developments. We do not know how or when these issues will be resolved. We are closely monitoring the implications of these developments for the U.S. economic outlook and, as always, we will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion (emphasis mine), with a strong labour market and inflation near our symmetric 2 percent objective.

And, suddenly, all market participants became happy; many started debating whether the Fed would cut the interest rates in the coming June meeting or in the July meeting or in the September meeting, and major stock markets around the globe started going up again. To put it differently, the Fed and its chair Jerome Powell responded to the bond market as they were “required.” In addition, the central banks of Australia, India, New Zealand, Malaysia and Philippines—all cut interest rates—and the European Central Bank, Bank of England and Peoples Bank of China have all turned dovish.

Furthermore, on top of other bad news regarding economic developments from around the world, on 7 June 2019, the US non-farm payroll report came way worse than expected. Only 75,000 additional jobs were added, while economists surveyed by Dow Jones had been looking for a gain of 1,80,000 jobs. This increased the likelihood of a US recession further and, therefore, the likelihood of a rate cut by the Fed in the near future. And, hence, the world equity markets have become even happier and most of the major world equity indices finished the week on a cheerful tone.

To Sum Up

The world’s major central banks had managed to avoid the risk for a self-fulfilling cycle of market instability and economic disruptions, as El-Erian (2019) warned on Monday for another week. Yet, despite some small variations at some maturities, the US yield curve remained more or less as it was at the beginning of the week.

So, who knows what is going to happen to the world economy and financial markets in the not-so-distant future?

Be the first to comment