Environmental, Social, and Governance investors must identify the actual elephant in the room

Counterbalance is a newsletter from a new anti-monopoly organisation, the Balanced Economy Project.

Cross-posted from The Counterbalance

To subscribe to The Counterbalance click Here

We have just co-published a new report, together with Denise Hearn and the American Economic Liberties Project. Rana Foroohar has written an excellent article about it in the Financial Times:

“Stakeholder capitalists, “while assertive about the obligations of firms in many areas, have been utterly silent” on instances of concentrated corporate power, says Denise Hearn, a senior fellow at the American Economic Liberties Project, and competition lawyer Michelle Meagher, co-founder of the Balanced Economy Project. They make a good point.”

Monopoly power – by which we mean excessive and durable concentrations of economic power – is a central blocker, if not the central blocker, on multitple intractable problems such as the erosion of democracy, inequality, or climate change, which are exactly the issues stakeholder capitalists are supposed to care about.

Whether you think stakeholder capitalism is meaningful or empty corporate puffery, ESG assets are anticipated to total some $50 trillion within three years: this is big, so it matters.

Here’s one example of the blind spot. JUST Capital, a non-profit stakeholder capitalism group, ranks America’s most ‘just’ companies each year. Who tops the list?

Why, the most “just” company of all 954 studied is Alphabet, parent of Google! A company that is widely accused of corrupting democracy, and has received some of the largest antitrust fines in history for abusive activity.

That’s quite some dissonance. How did this happen?

Box: what is stakeholder capitalism?

Stakeholder capitalism self-identifies as a movement that aims to de-emphasise or undermine Friedman’s idea of shareholder primacy, in favor of focusing on the many stakeholders a corporation has: customers, workers, suppliers, communities, and the environment. ESG is closely related: it refers to the investments themselves that fulfil supposedly “good” environmental, social and governance criteria.

Chicago!

One root of this dissonance lies in a dinner party in 1960 at the Chicago home of the economist Aaron Director. His 20 dinner guests included Milton Friedman, George Stigler, Ronald Coase – and our old friend, the lawyer Robert Bork.

Director, whose sister Rose was married to Friedman, was a pugnacious former radical left-wing union organiser who had crossed far over to the other side and seemed hell-bent on smashing the consensus that once fed his idealism. Director’s politics were “pure free market,” said Matthew Watson, Professor of Political Economy at Warwick University. “There can’t have been many house guests that the Friedmans would have had where Milton would have been accused of being too pro-government and too left wing.”

Director “gradually destroyed my dreams of socialism with price theory,” Bork later said, adding that many of his colleagues “underwent what can only be called a religious conversion” in his economics classes.

At the dinner, Coase presented a paper, “The Problem of Social Cost.” Corporations in those days were supposed to be subject to the law. If a corporation was pumping illegal pollutants into a river, say, government confidently went out and stopped it. (After all, who else would?)

Coase wasn’t having it. “Externalities” like pollution weren’t necessarily a problem, he said, as long as you squeezed the whole picture into a cost-benefit analysis machine, where you weigh the costs of that pollution against the benefits (to shareholders) from not having to pay to clean up. Or take an aggressive banking monopoly, or a multinational using tax havens to cheat on their taxes: you could make the same arguments. If the winner benefited more than it cost the loser, then the result was ‘efficient.’ Let the polluter pollute!

Stigler remembered wondering “how so fine an economist could make such an obvious mistake.” At the start of the evening Coase summarised his idea and a vote was taken: all 20 guests opposed him.

Laws and their application, in Coase’s eyes, should be subjected to this cost-benefit analysis. And who would be the judge of what was right and good? Why, economists, of course! Including the very people, nearly all men, in the room. It was the basis for a stunning power grab. Screw the law.

The dinner progressed, and the arguments mounted. “As usual, Milton [Friedman] did most of the talking,” Stigler remembered. “My recollection is that Ronald didn’t persuade us. But he refused to yield to all our erroneous arguments. Milton would hit him from one side, then from another, then from another.” But then, like the plot of Twelve Angry Men, the mood began to change. “To our horror,” Stigler said, “Milton missed him and hit us.”

By the end of the evening they took another vote: all were for Coase. “I have never really forgiven Aaron for not having brought a tape recorder,” Stigler said later. “It was one of the most exciting intellectual events of my life.”

Exciting for the economists, certainly. But devastating for anyone at the sharp end of pollution, or tax haven-based criminal activity, or monopoly power.

Screw the law, screw the little people

The guests went out and many, in their own way, spread Chicago religion.

Friedman complemented Coase’s ideas with his famous 1970 doctrine of “maximising shareholder value”. Whereas Coase had called for an overall cost-benefit analysis between a firm’s different stakeholders, Friedman took a firm side on which stakeholders to favour. He chose corporate shareholders – the winners from sketchy corporate behaviour like pollution or tax avoidance or monopoly abuses.

Friedman argued that if corporate bosses focused only on delivering value for shareholders, they would increase profits, wealth would trickle down, and society would take care of itself.

Bork, for his part, developed a related approach, more finely tailored to help monopolists. In his 1978 bestseller The Antitrust Paradox, he argued that regulators and courts should stop worrying about power and market structure and law — or about the interests of workers, small businesses, or citizens — and instead assess only the internal economic efficiency of corporations, and the welfare of consumers.

This consumer-efficiency focus is a slippery (and well-funded) slope towards arguing that bigger is better, as you get economies of scale and scope that trickle down to consumers – and since everyone is a consumer, it all comes out in the wash.

This focus on consumers and prices was an easy sell in the high-inflation 1970s: much easier to have people focus on the price of groceries than to campaign against the often more complex and time-delayed harms that monopolists inflict. (Alas, we are plunged into in a similar era today, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.) These ideas eventually became so influential that they now dominate the thinking of most competition authorities, courts and competition scholars, worldwide.

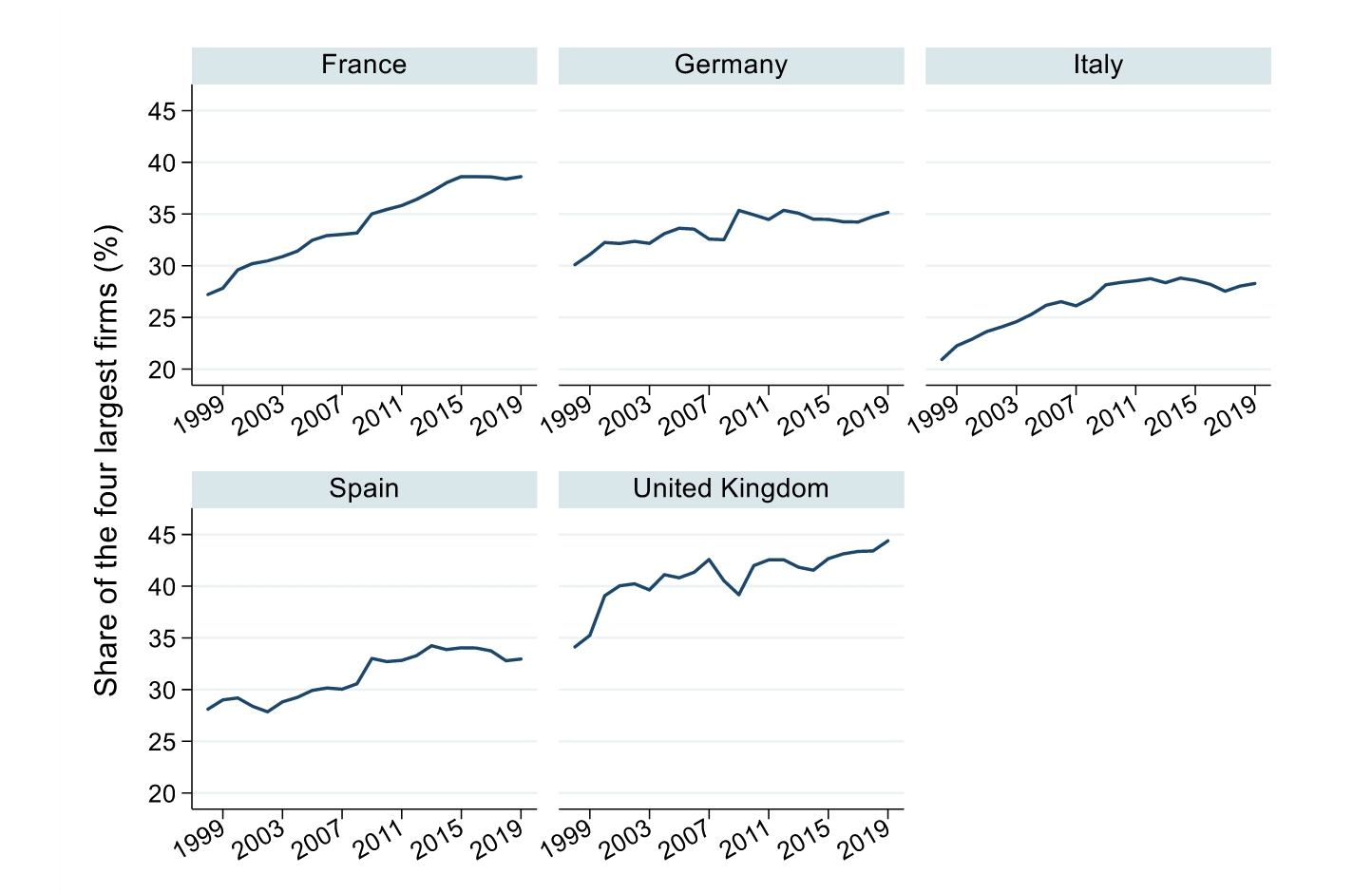

Here is a new paper, showing some effects of rising concentration across a range of industries in selected countries:

In all countries, more than two thirds of the industries measured experienced an increase in concentration.

Even though Europe is probably less monopolised than the United States, Europe is also in a terrible state, with (just for example) less than 0.5 percent of notified mergers blocked in recent decades. We have pointed this out, more than once. Here is yet more evidence, underlining the point.

Make no mistake: Europe has a terrible monopoly problem, a foundation for much of the extremist politics we are seeing today. Plenty of blame lies at the feet of Director, Coase and Bork.

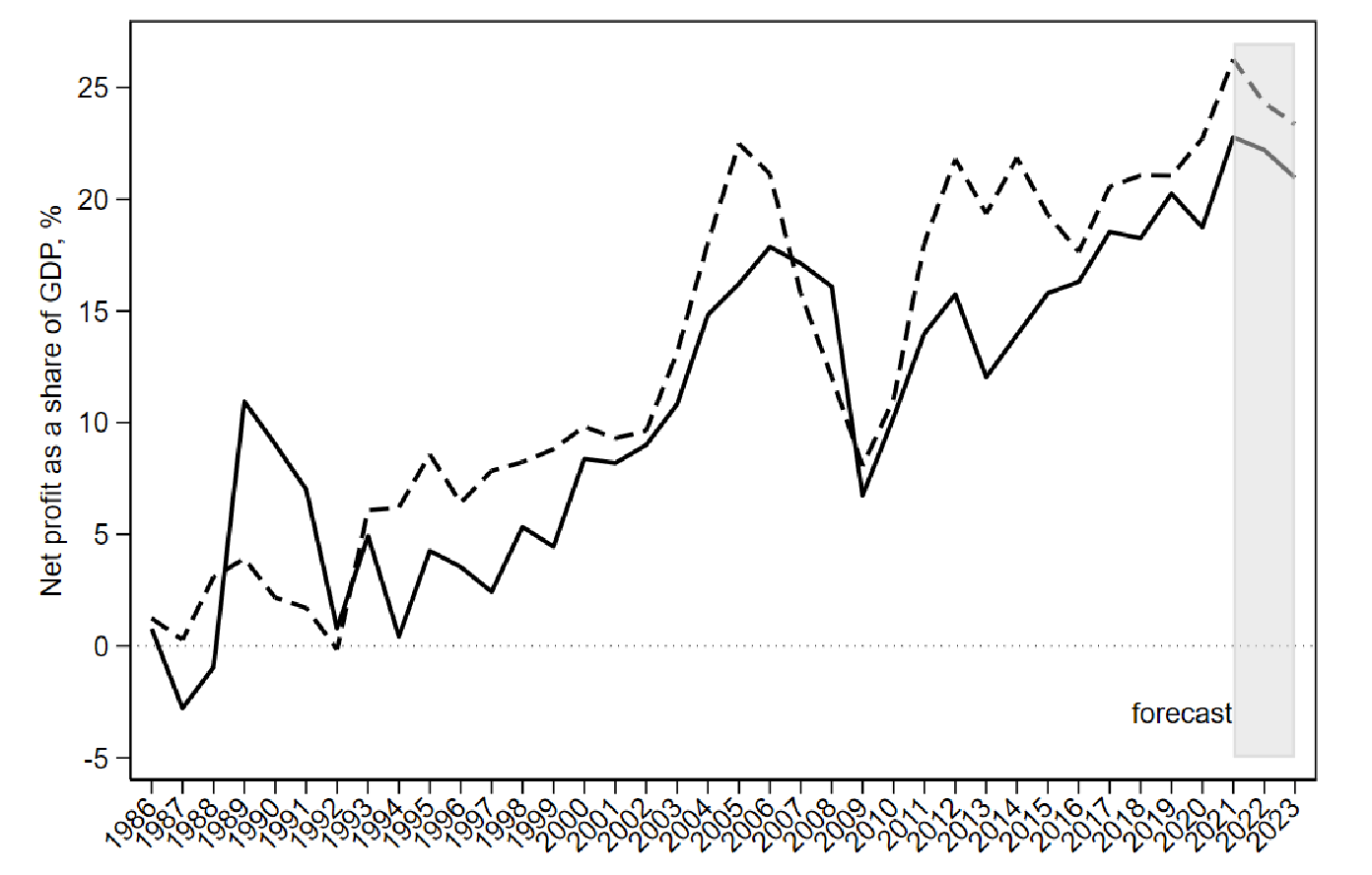

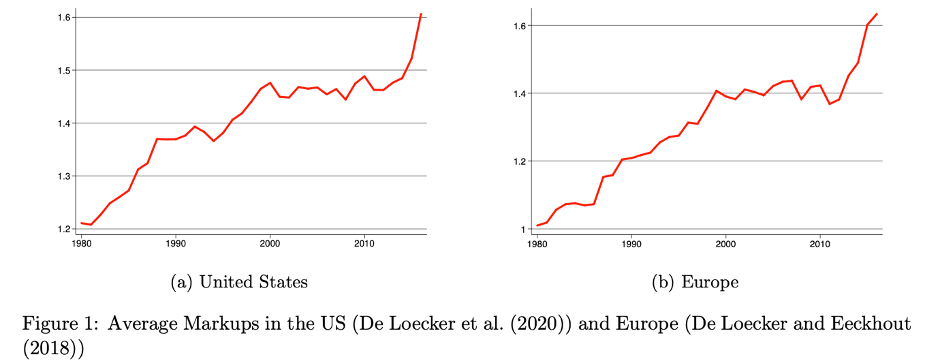

The funny thing is, this heavy focus on consumers and prices has backfired — and for obvious reasons. Monopolists don’t need to pass on the fruits of any ‘efficiencies’ (if there are any) to consumers – because monopolists have the power not to! Here’s another picture, of “markups” (how far prices are above production costs) to show it.

And any ‘efficiencies’ a monopolist may pass on to its own workers is more than counteracted by harmful “gravitational” effects that it exerts on other firms and their workers, caught helplessly in the monopolist’s orbit.

There’s another way that the ideas of Friedman and his allies backfired. They worried that pursuing broad stakeholder interests would make firms dangerous arbiters of political life. Friedman would have hated today’s stakeholder capitalists, and would have joined today’s conservative critiques of “woke” corporations.

Yet the problem is not wokery: it is that corporate bosses now have so much power. By elevating corporations above the law, and by promoting monopolisation, the Chicago men ushered in the very outcome they sought to avoid.

Stakeholder Capitalism to the rescue?

Stakeholder capitalism is supposed to embody a rejection of Friedman’s ideas, as corporate executives are pushed to widen the focus beyond just making shareholders rich, and consider those other stakeholders affected by corporate activities.

It is interesting to compare the two movements here: stakeholder capitalism, a global movement, and anti-monopoly, which is currently mostly happening inside the United States. (We at the Balanced Economy Project plan to spur an international movement.)

These two movements rarely intersect, even inside the United States — though they clearly share plenty of common ground. As our report notes:

“Both [movements] ask fundamental questions about the nature and obligations of firms in society. Stakeholder capitalism generally focuses on what happens inside corporations, while anti-monopoly focuses on what happens between corporations, in markets and economies. These terrains overlap in important ways.”

Yet they are passing each other, like dark ships in the night.

“Stakeholder capitalists, while assertive about the obligations of firms in many areas, have been utterly silent on the concentrations of economic and political power that firms like Google represent.”

Is rapprochement possible? Well, both movements are divided into two broad camps. A first camp, in each case, includes those who sincerely want to challenge and transform the economic system, sharing and decentralising power through systemic reforms for workers, consumers, citizens, independent businesses and so on.

The second group is more cynical. For shareholder capitalists in this group, the movement is useful as a tactic to forestall regulatory intervention and thus preserve the status quo, and also to attract money from gullible investors who think they are doing good. In the anti-monopoly case, the second group involves a large “competition establishment” who are deeply invested in competition policy, but who use “consumer welfare” and “efficiency” as their lodestars, and as legal cover for monopolisation.

Our hope with this paper is to start to bring together actors in both movements, especially in the first groups, who genuinely want to create structural change to rebalance power across the economy.

There’s work to do

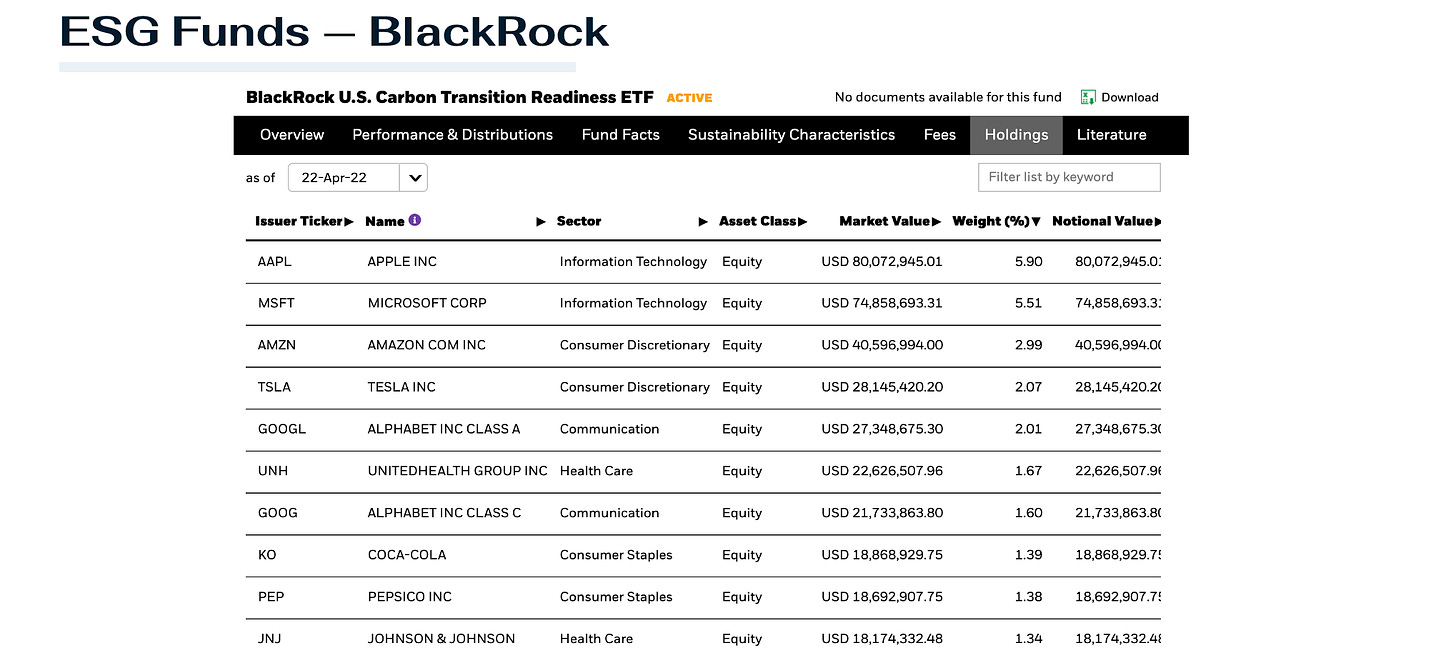

Here’s a close-up of a major ESG fund.

Will you just look at that list of monopolists: each, in its way enjoying major market power.

At number three “best” firms is Amazon. Denise Hearn provides another way of looking at the behemoth.

That’s right: Amazon’s awesome market power enables it to exact eye-watering tolls or private taxes on the independent businesses on its platform. For the simple reason that the sellers have no alternative but to be on Amazon. And it is spreading into everything. For example, New Scientist magazine has a new article entitled “Is Amazon going to dominate space?” in which it asks “will the tech giant’s attempt to corner much of the launch market quash the ambitions of smaller satellite operators?” Hugh Lewis, a UK space scientist, asked “If Amazon has kind of absorbed most of the launch capability, what’s left for everybody else? Where do other operators go to launch their systems?”

It’s yet another indicator that it’s high time to rein them in – properly. Among other things: Break. Them. Up. Get Amazon out of space, and let the rest in.

Solutions, for stakeholder capitalists.

Stakeholder capitalists can support many anti-monopoly solutions.

For example, they could support international versions of US President Biden’s whole-of-government approach to competition, as laid out in his July 2021 executive order; support authorities investigating anticompetitive mergers and break up dominant companies; investigate coercive and one-sided contract terms that harm workers and small businesses; update merger rules and guidelines; reverse the burden of proof for merger approvals; and back more research on the scale and nature of the world’s growing monopoly problem.

A foundational tenet of any democratic economy is that corporations are fundamentally embedded in society, as public creations that should be publicly accountable, and that markets are structured by politically determined rules. If the stakeholder capitalism movement is to tackle its internal inconsistency, it has no alternative but to embrace the new anti-monopoly agenda.

See our Executive Summary here, and our report here.

Support us and become part of a medium that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment