The Gig Economy Project speaks to Sheffield Stuart Delivery striker Khalil Lange and IWGB branch secretary Jake Thomas about the longest strike in the history of the UK’s gig economy

BRAVE NEW EUROPE has made a further donation to the IWGB Strike Hardship Fund. Let us all show our solidarity and support these workers at a difficult moment. Donate here

The Gig Economy Project, led by Ben Wray, was initiated by BRAVE NEW EUROPE enabling us to provide analysis, updates, ideas, and reports from all across Europe on the Gig Economy. If you have information or ideas to share, please contact Ben on GEP@Braveneweurope.com.

This series of articles concerning the Gig Economy in the EU is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Andrew Wainwright Reform Trust.

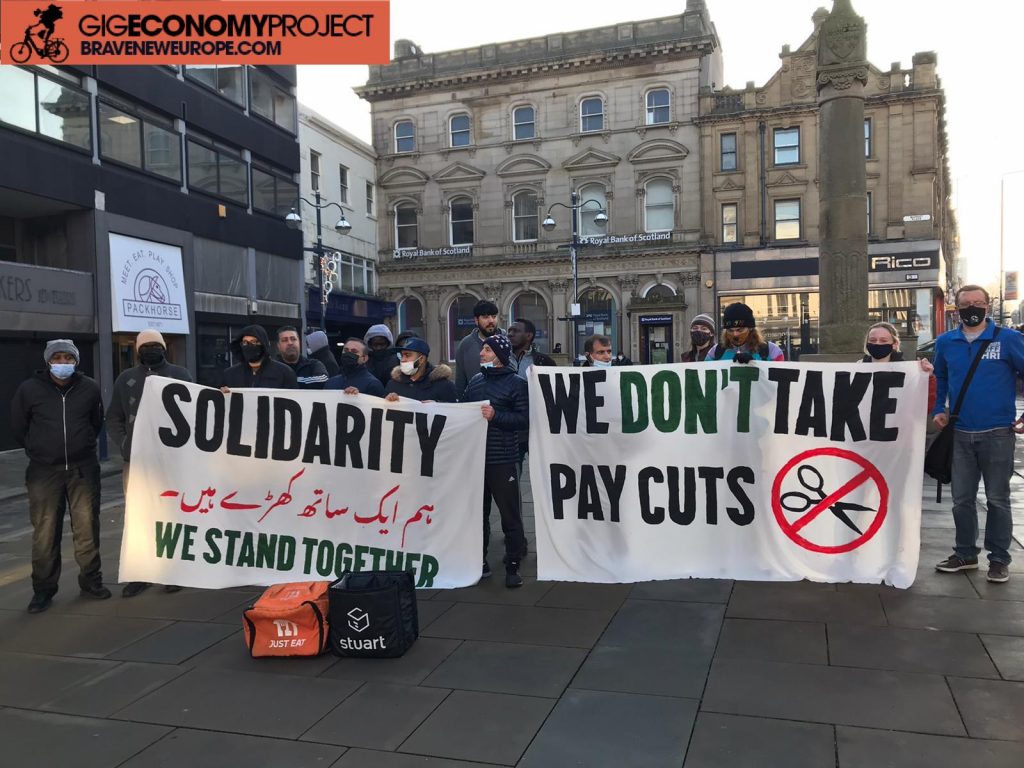

THE Stuart Delivery strike is the longest ever in the UK’s gig economy. Initially running for 18 days from 6-24 December, it re-started again on 10 January.

Starting in Sheffield, the strike spread to six towns and cities across the north of England, and the couriers, members of the IWGB union, plan to continue until their demands for higher pay are met.

In this Gig Economy Project podcast we are joined by Khalil Lange, Sheffield Stuart Delivery courier and one of the strike’s leaders, and Jake Thomas, a courier in London and the IWGB’s courier branch secretary. We discuss:

01:12: Lange’s journey to becoming a courier and trade unionist, and how the strike got started

03:21: The spread of the strike and what makes it unprecedented

07:49: The mood of the strikers and the attitude of the company

11:59: Just Eat and sub-contracting

15:00: The dispute over Stuart Delivery’s “linear pay” system

19:58: The current situation on the ground

22:45: The historic significance of the strike

25:19: How can people support the strike?

AN ABBREVIATED TEXT VERSION OF THIS INTERVIEW IS ALSO AVAILABLE BELOW

1:12: Gig Economy Project: Khalil, tell us a bit about how this all got started for you.

Khalil Lange: I got into this because I had a motorbike accident, I was working in an office, and I was nearly killed on my way to work. The management didn’t care, because they didn’t have any care for life they just wanted you to be in work. I quit that job, and I said I wanted to do something where I was independent, that I could do myself. A courier seemed like a really good option, it allowed me freedom, it allowed me to do what I wanted. So about three years ago I quit my job, bought a new motorbike because my other one was wrecked, and started doing the job.

I got in with the union very recently. I didn’t know we had one. I had always joined the union when I worked somewhere, but I didn’t know couriers had a union it didn’t look like somewhere where you’ld have one. It wasn’t until we started having issues with the pay, and I was talking to Parirs [Sheffield IWGB courier], and he said ‘yeah I’m part of the union and we’re fighting’, and I said ‘well, I have to get into the union then’, because I’ve always been an advocate of wherever you work, whatever you do, join the union, it’s good for you.

2:32: GEP: What was the process that led to the strike happening?

KL: It was Parirs, he just said ‘enough is enough’, he looked at it and said ‘this is nonsense we’re not doing it’. He started speaking to couriers to gauge the feeling, contacted the union and said ‘is there anything we can do?’ and the union said ‘yeah you could strike, you could do something’. We just kept chatting away and getting support and it kind of grew from there. We had a meeting, and decided that strike action was the best option and just ran with it.

3:21: GEP: One of the remarkable things about this strike is the fact it spread from Sheffield to Chesterfield, Sunderland, Huddersfield, Blackpool. How did that happen?

Jake Thomas: It’s been really interesting because Sheffield has been kind of like a recipe for all these other places. There have been sporadic, very temporary actions in places like Chesterfield before hand. It seems a lot of cities are very annoyed with this new pay structure and they wanted to do something.

Sheffield has been acting as this demonstration of how you can have sustainable gig economy action, how we can bring people in without putting precarious workers at risk. So people are looking to Sheffield and places like Blackpool, Huddersfield and Sunderland, and saying ‘if they can do it then so can we’.

Because usually gig economy strikes last just one or two days; maybe you can do a temporary boycott and a demonstration. This has been absolutely unprecedented in how long it is. It’s kind of acting as a beacon of hope.

05:02: GEP: You mentioned that it’s been the longest ever gig economy strike in the UK. Why has it been different?

JT: There’s a few reasons, one of which is that after the pandemic couriers have really realised their worth. We’ve been told for years and years that we are expendable workers, ‘if you decline work someone else picks it up, even if 95% of the workforce strikes the other 5% is going to be really incentivised to pick-up that extra work’. But having experienced being out on the road ourselves in the pandemic, we are starting to realise we are integral to the functioning of these companies and we have a lot more leverage than we ever realised.

Another thing is just the formula, the way they’ve been going about the strike in Sheffield, has made it a lot easier to sustain for people in difficult financial situations. They’ve been targeting certain high profile restaurants, so in Sheffield it’s been McDonald’s peak times in the evening. This means that couriers can still go to other places, can still work at other times in the day. We’ve been raising money for a strike-fund that has been really integral so that people don’t have to give up peak-hour income just to keep this going. Because a lot of the time people really want to take action, they do it for a day, but they’ve got bills to pay, kids to feed, heat and gas and stuff like that, and it’s completely unsustainable.

So we’ve found a way, working with volunteers and activists locally, making sure we are targeting things really, really specifically and quite stringently attacking certain points rather than just having a blanket ‘no one can work’. Which means that people can still keep working but we can really, really push these pressure points on Stuart [Delivery].

We are on day 21 now, so it’s something that’s been able to keep going, and even though Stuart Delivery have been trying to wait things out, a week after that the response starts to change, and we’re now into week three or four and you can kind of see them going ‘okay we kind of need to do something about this now’.

So it’s been pretty inspiring to see. And I think people from other gig economy companies, like Deliveroo, Uber Eats, can look at this and go ‘that’s how we can do it, that’s how we can take action and actually make it sustainable without doing a couple of days and everyone going “right we can’t do this anymore”.’

07:49: GEP: For many of the workers this must be the first time they have ever been on strike, and it’s been such a long strike – how has the mentality of workers changed?

KL: I’ve been quite fortunate not just to gauge the atmosphere in Sheffield. Yesterday I drove over to Sunderland for a meeting, that’s twice I’ve been there, and I’ve been to Blackpool; I’ve been up and down the country.

At first they were hesitant about whether or not it was possible. They were doing [the strike] but they were wondering ‘are we going to be able to sustain?’, ‘is it going to get the results we want?’ And then we start getting these little moments where [the company] get in touch and start reaching out. And we put the word out that ‘the only reason they are doing this is because of what we’re doing, they’re scared, when you force a company to respond it shows they are worried about you not the other way around, so hold it.’

As we’ve held for longer, other workers – even if they are not on the strike or on the pickets – they see us [on the pickets], they know what we’re doing, they go ‘we will leave, we will go somewhere else [for work]’. So we hear the affect from the McDonald’s managers who say they are ‘having issues, we’re losing money, etc’, and that gives the guys that confidence that we are actually succeeding so keep it up. And when Stuart Delivery come out and have a face-to-face meeting, that’s just made everybody feel like ‘yeah as long as we hold out we will get the win’.

So the morale at the moment is really high. Yesterday in Sunderland I saw that their morale is right up through the roof, they’re buzzing, and they are arranging a bunch of meetings today to start action possibly this weekend and to get right back at it after the break as well. The morale nationally is extremely high. Couriers are willing to go the long haul, they’re quite set, they’re saying ‘yeah we can do this two months, three months, four months’, we know it will work.

10:17: GEP: What about the mentality of the company? As I understand it, Stuart Delivery were basically ignoring the strike at first. Then they put out a tweet defending their pay structure. Then they had a meeting with a pre-selected group of couriers, and the IWGB organised a protest there. Do you think the company is realising it has to take this seriously, it has to negotiate?

KL: 100%. I think they thought that if they just ignored us for a week and put the [pay] multiplier up, couriers would just go back to work.

Deliveroo [couriers] attempted a strike at the beginning of last year and they did a drive around and they were on strike for the day, and it just fizzled out. I think [the company] just thought this would be the same: ‘some drivers will strike, some won’t, the guys that won’t will get annoyed at the ones who do and then everyone will go back, so we’ll just wait.’ I think their mentality has changed massively, because they were waiting for the ‘stupid couriers’ to just stop striking and we’re not.

And the bad publicity is getting immense for them. They have politicians getting on at them, they’re getting phone calls from McDonald’s, Just Eat, and I think they are starting to realise. I think they are far more worried than we are, and I think their mentality is ‘we better do something, because these guys aren’t going to go away’.

11:59: GEP: Jake, you deliver for Just Eat in London, and of course Stuart Delivery is a sub-contractor for Just Eat in Sheffield, you have a different sub-contractor there [RanStand]. Tell us a little bit about Just Eat’s role in this.

JT: I think Just Eat has always been the smallest of the big three food delivery companies [in the UK]. There’s Deliveroo, Uber Eats, and then Just Eat is kind of the odd one out. So they’ve needed other ways to compete with those two. And over the last year in places like London, Liverpool and Brighton it’s been ‘well you can get quicker times from Deliveroo and Uber Eats but we are actually treating our couriers ethically’. They have these posters with ‘guaranteed £10 an hour, holiday pay, sick pay’.

The catch is obviously that there is a sub-contractor which means RanStand and Just Eat point the finger at each other, and you get absolutely nowhere. There’s pretty much no reason for us to be sub-contracted at all, it functions pretty much the same as a normal employment would, except for the fact it’s such a pain to get a lot of these employment rights, and we are not actually legally obliged to a lot of it.

Earlier last year we had reports that Just Eat were actually going to phase out Stuart Delivery couriers completely, they were going to bring in this new hourly pay model in places like Sheffield. And for a lot of people that’s not what they want. We can have ethical treatment of gig economy couriers and still retain that flexibility and still retain that freedom, like Khalil was saying. There doesn’t need to be a complete revamp of how the model works. So these guys are really adamant that we can retain these things, we can still be as flexible and free as we want, but really simple things can be done, like the demands we are asking for at the moment: the £6 base rate, holiday pay and sick pay, proper insurance and stuff like that, which aren’t in conflict with free log-in and flexibility.

But somehow Just Eat manages to always pick the worst options. They restrict the times you can log-in and don’t really give many benefits with that. So regardless of what they are putting on the posters, they are always trying to shift the blame to sub-contractors, they are always trying to do it as cheaply as possible, they’re always trying to dodge these big commitments that they should be making as ‘ethical employers’.

15:00: GEP: The dispute between the IWGB and Stuart Delivery over the company’s new pay system called “linear pay”: the IWGB say it has cut the base rate of pay by 24%, but the company denies that and says it’s not true. Can you help clarify this?

KL: I put out a pretty interesting tweet in reply to their tweet. They said ‘look we’ve done the maths and it works and you guys are making the same money’. And as an actual driver in the city, I saw exactly what they did.

When we were still on the old pay system, the multiplier – the bonus that we have on each order – was put almost to the floor or non-existent. It really dropped off and we weren’t really making any money. They brought in the new payment structure, this ‘linear pay’; £4.50 used to be the minimum, it now starts at £3.40, but the multiplier shot up to .4, so you are talking an extra £1.50 on top of every order. So they were able to look like we were making the same money at the end of the week because the money kind of comes out similar, but we’re not soft. I know when I’m being fed extra bits. I can see that the multiplier is 1.4 or 1.5 now when it wasn’t before.

Sunderland at the weekend, they had their multiplier completely cut off, they had none running all weekend, and there was no money to be made. They were making £3.40 at three jobs an hour, that’s £10.20. Your fuel bill for the week is £140, your insurance bill for the month is £180, you are going through tyres at a rate of knots, break pads at a rate of knots, at £10.20 an hour it’s not even enough; you can go to Tesco and get £11 an hour.

So for a job that is demanding as it is, and as expensive as it is, the linear pay structure is just a slap in the face for people who have risked their lives through the pandemic to help make the company an awful lot of money. They are trying to push this agenda that it works and it just doesn’t. It causes more problems than anything else, and they have more cancellations through the linear pay than through the old structure.

JT: A lot of their communications early on was just complete stonewalling; this really patronising attitude towards the riders. They have these big Zoom calls with the staff, they would be marketing it as a feedback session with riders, but it would essentially be one guy telling the riders ‘no you are wrong, this is going to be great and you are going to love it’. Any time a rider would put forward an argument like Khalil’s, or mentioning the insane rises in the cost of living, or mention the insane costs they have to pay, they would be coming out with stuff like ‘no, no, no you just don’t get it’.

Thankfully that line has deteriorated a bit over time as they’ve realised it’s not sustainable and that we have the arguments and the evidence, and that they do need to actually listen to us.

19:58: GEP: So you stopped the strike on Christmas Eve and then re-started again on Monday, 10 January. What’s the situation with the strike now?

KL: We have six cities currently either involved in strike action or discussing re-starting strike action. We [Sheffield] are picketing three restaurants at the moment, Chesterfield are doing two, Blackpool are doing two, and Sunderland are talking about doing another two. We started off with a really large number of [McDonald’s] restaurants at the beginning, we were hitting six and maintained six I think over 15 days, because we knew we had to make a really big impact. Now that we have communication from the company we know we don’t have to make a big impact we have to make a sustained impact, so we have whittled that number down a little bit to make it just a bit easier for couriers and picketers, with the understanding that if they even remotely think it’s easing off and try to take the mick we will just lock all six back off. So it’s a fair number of restaurants locked off at the moment.

We have had communication from other cities and other places, and we are just reaching out to them at the moment just to gauge what they are thinking and what they are up to. If we find out they are going to host a meeting or are going to do something, either someone from the union, me or Parirs, we just fly down there and help them out. We discuss with them what we’ve been doing, finding out what the issues are in their city and how it’s best to strike.

Chesterfield didn’t strike in the same way as Sheffield did as it just didn’t seem feasible, it wouldn’t have made as much of an impact as it’s a different environment. They locked off two KFC’s and two McDonald’s, because for them that was the smart option, that was the way they could do it. So it’s one of those where we go down and find out what works for them and that’s how we tailor the strike. Each city’s different, their economy is different, where they order from is different. So we don’t just go down and say here’s the rubber stamp you need to copy it, we go down and talk to couriers and say ‘how do you guys think it’s best for you to fight?, how can we help with your fight?, but just know that it’s not only you fighting, whatever you do, Sheffield is with you, Blackpool is with you, Huddersfield is with you, Sunderland is with you, Chesterfield, Rotherham; we are all with you and so is the union’.

So it’s interesting, it’s flexible and varies depending on where you go because everywhere is different.

22:45: GEP: The strike has been an inspiration not just in the UK but internationally. Are you aware of the significance of the strike – this hasn’t happened before in the gig economy, so it’s something historic. Is that something you guys are conscious of?

KL: 100%. We are in Sheffield, the steel works city; they were striking way before we were born. I’m from Liverpool, I’ve heard about the dockers strikes, the rates riots, I’ve heard about these big movements which happened. You’re thinking all these big fights have gone. We won freedom, we fought fascism, we fought for equal rights, there’s nothing left to fight for.

And then you find yourself in a movement that has hundreds of thousands of people, not only involved in it but also supporting it and commenting about it. And you start getting messages from Hong Kong, and you are like ‘how does Hong Kong know that me from Sheffield is striking outside McDonald’s!?’. Australia, Canada, America, messages from Italy – they started to do their strike and they sent us a message saying ‘we’ve seen what you are doing’. We know all of a sudden that it’s not just this localised little thing where we are arguing against our boss saying why did you take our money, it’s this international thing. We made the news in Poland, and we were like ‘why were we on the news in Poland!?’.

I think everyone knows that it’s definitely a big thing, and that inherently adds to people being willing to do more, because we know that if we hold out and if we win, that we pave the way for everyone else in the same economy that we are in to say ‘they did it, it works, we can do it’. We tell every Uber and Deliveroo guy we see while we are striking ‘you know you guys are next, when we finish our strike you guys are next, you are going on strike’. And they are all like ‘yeah!’, the Uber drivers say ‘if you guys win this and the union can help we’ll strike!’. And we say ‘good, because that’s what we want to do next: we want to finish with our company, and then march on down and take on the next one’.

So, yeah it’s a good feeling. It’s a feeling of accomplishment.

25:19: GEP: What can people do to support the strike?

JT: We’ve got the hardship strike fund you can donate to. We’ve just launched this letter writing campaign to the CEO Damian Bon, and we’re copying in all of Stuart Delivery’s other clients, really trying to pressure them to say ‘look at what your delivery partner is doing, look at how disgusting this is’. And we’ve got about 700 e-mails sent since mid-day yesterday.

Any kind of support will be appreciated. We’ve had people passing motions of solidarity at constituency labour party’s and Momentum groups, donating to the strike fund, and just publicising that. Another big thing people have been doing is just spreading it to their own cities. There have been people in Leeds, non-couriers, just people who have seen the strike who are now going to restaurants, talking to couriers coming in and out and saying ‘have you heard about what’s going on in Sheffield and Blackpool, maybe we should do that here’.

27:07: GEP: And you are ready to dig in for the long haul if that’s what’s necessary?

KL: Hell yeah. We are already set. We’ve discussed it and we know that, given the way we have set it up, we can do this for six months, eight months, a year. We can hold this down and do it indefinitely, and I think there’s a mentality with the couriers that ‘we should’.

Because it’s a blatant smack in the face to a group of people who were the complete driving force during the pandemic. People always think of us as just KFC or McDonald’s couriers; we were also delivering supplies to old ladies scared to go outside, we were delivering Superdrug prescriptions to people who were isolating, we were dropping off Apple products to kids who were home-schooling. We were instrumental in keeping the whole city moving.

So we know that what has happened now is a ‘thanks for all your help, now off you go’ kind of deal, and we are not willing to take it, because we know that if we take it, it won’t stop there. If we stop now we just invite them to know that they can get away with murder. So if we have got to maintain this strike for ten years, well, my kids will join me on the picket line when they’re older!

Be the first to comment