The 400 kilometre ‘Great Delivery’ from Paris to Brussels starts this Sunday [5 November]. Piero Valmassoi, freelance journalist and platform economy expert, spoke to Camille Peteers, rider and spokesperson for the Brussels Couriers’ Collective (Collectif des Coursiers Bruxelles), to find out what it’s all about.

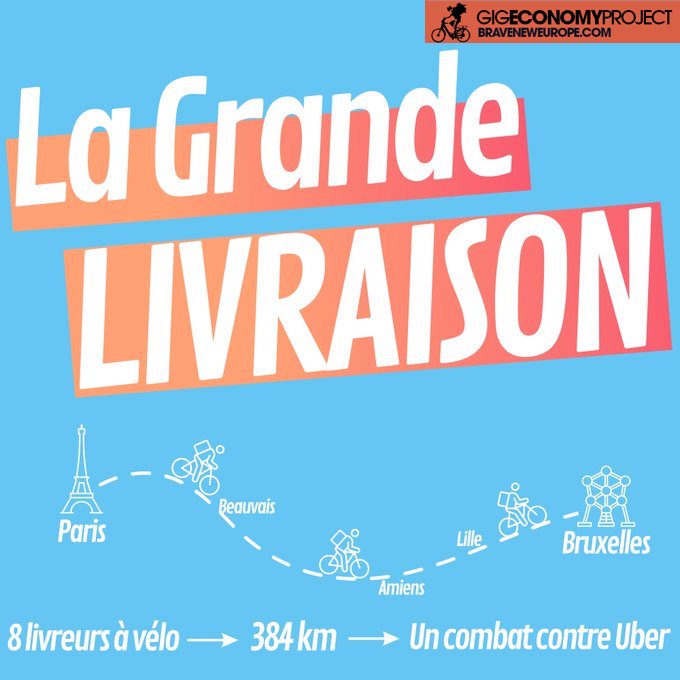

From 5-8 November, eight delivery riders from six different countries will ride their bikes for 400 kilometres from Paris to Brussels in ‘The Great Delivery’. The initiative has been organised by delivery riders’ organisations RidersXDerechos (Spain), La Maison des Livreurs (Belgium), Riders Collective (Austria), FD SUD Commerces et Services (France), and the federation of bike messenger cooperatives CoopCycle.

The aim is to deliver their demands to EU policymakers in Brussels for a strong EU Platform Work Directive and to limit the lobbying power of platforms. Every day, they will stop to meet and discuss with other workers that are subject to ‘uberisation’ – care workers, graphic designers, cashiers, tour guides. They will be accompanied along their way by ride hail drivers in solidarity.

On 8 November, they will arrive in Brussels and hold a commemoration in memory of Sultan Zadran, a delivery rider who died in February in a road accident. A meeting will also be held with Leïla Chaibi MEP, the Belgian union of platform drivers UCLB (Union des Chauffeurs de Limousine de Belgique), and the Union of domestic workers (Ligue des travailleuses domestiques) at the Brussels House of Riders.

The day after, 9 November at 1 pm, riders and drivers will hold a demonstration called “Don’t let Uber make the law” in front of the EU Commission building. This is the next scheduled date for ‘trilogue’ negotiations between the European Parliament and Council of the EU over the Platform Work Directive.

Ahead of The Great Delivery getting started in the French capital, I spoke to Camille Peteers, a French-born rider who is now a leading trade union activist in Brussels’ Couriers Collective, about how the initiative came about, what the position is of the riders in respect to the Platform Work Directive, and the importance of transnational cooperation between platform workers.

PV: Can you explain how the idea of The Great Delivery was born?

CP: We are a group of riders and activists who have been in contact for some time now. The idea of “The Great Delivery” came from Jeremy Wick, a French rider who worked for platforms for years and has launched the cooperative Blackbird Bordeaux, to provide an alternative to big platforms, starting from offering decent wages for riders.

The idea was born during the last Trade Union Platfor(u)m by the European Trade Union Confederation in September in Madrid, where it became clear that the Platform Work Directive is not going in the right direction. The objective is making the work of activists at local level visible and making sure the claims of uberised workers are heard by EU politicians.

PV: Why did you decide on this form of demonstration?

CP: This demonstration originates from the idea that platform workers and other precarious workers should provide visibility and give a clear picture of their working conditions to politicians, who must listen to their demands. This is why riders participating to The Great Delivery will meet and discuss along their way with different workers’ organisations, such as the Belgian Union of Domestic Workers, with workers of the construction sector, and workers who are undocumented migrants.

READ MORE: Organising from the bottom-up: Inside Brussels’ House of Couriers

We have chosen this method to put in the spotlight our demonstration of 9 November in Brussels in front of the EU Commission building, “Don’t let Uber make the law”, because we do not have any other means. We do not have millions of euros like the platform lobby to make an impact on the EU Directive; instead, we have the people, and we try together to create an alternative and a bottom-up lobby, which can counter the action of the powerful platform lobby.

PV: What is your position on the EU Platform Work Directive? Is there a unitary position on the Directive shared by the collectives that will participate in this action?

CP: As for the Brussels House of Riders, we think that there should be a mechanism that allows to properly reclassify platform workers, going beyond the current situation of bogus self-employment. This mechanism would finally be able to stop case-by-case court decisions on platform workers’ legal status. This is a lengthy and costly process for the workers, and it is instead aligned to the interest of platforms, who use every means at their disposal to gain time. The mechanism I am talking about is the general presumption of employment for platform workers, as in the EU Parliament’s proposal.

There are certainly common points among the positions of the collectives that participate in The Great Delivery. First, we demand a general presumption of employment without criteria for platform workers.

We want to eliminate from the text the exceptions guaranteed to Member States that have already put in place forms of social dialogue, as we have seen that in countries where it has been put in practice, it is only a parody of social dialogue. In France for example, platform workers representatives that are involved in the government’s social dialogue process have no real representativeness; instead, this is a way to legitimate a legal status against which we fight, namely bogus self-employment.

READ GEP’S NEWSLETTER – Platform Work Directive: Avoiding “a gingerbread house”

We also demand that the EU Directive addresses the lack of recognition by platforms of the unions and collectives that truly represent platform workers. It is not acceptable that there is no structured channel of communication between the platforms and their workers. Concretely, this translates into the practice of unfair and arbitrary robo-firings of platform workers that we experience daily here in Brussels, in Spain, in France, and everywhere in Europe.

The EU Directive must fix this imbalanced situation, in which platforms have all the power over their workers, and it must acknowledge the crucial element of the unions’ recognition. It is about creating norms that allow for decent conditions and not to come back to a situation of modern slavery.

PV: You have talked about the need for platform workers and other precarious workers to join forces. Food-delivery couriers and ride-hail drivers are subject to the same exploitative employment model, but often have different profiles and demands. How do you put in place coalitions between couriers and drivers? Will drivers participate to the demonstration of 9 November?

CP: The Brussels House of Riders has always had a comprehensive vision of this struggle, aimed at the alliance of all workers. The Brussels House of Riders is the result of a coalition of unions, such as the Young FGTB and the CSC, social movements such as the MOC (Mouvement Ouvrier Chrétien), and collectives such as the Brussels Couriers’ Collective.

We have always worked together with organisations that represent ride-hail drivers, such as the UCLB (Union des Chauffeurs de Limousine de Belgique) and the BDP (Belgian Driver Platforms). Both organisations will join the demonstration of 9 November, as they demand that the EU Directive also take into account their claims.

Their demands could seem different from the ones of riders, as they demand to be self-employed, while we advocate for subordination. In reality, we both ask for a directive that allows a real distinction between subordinate workers and self-employed, which prevents workers from being falsely considered independent, when being subject to a situation of subordination vis-à-vis the platform.

Ride-hail drivers will not only participate in the demonstration of the 9 November, but they will also come to the House of Riders on the 8 November to meet the riders that participated in The Great Delivery and exchange experiences about their working conditions.

I think that it is essential to foster this alliance because of the drivers’ knowledge of how platforms work and because we share many demands, such as an end to unfair account terminations, the right to access personal data, and the need to establish a structured dialogue between workers and platforms.

PV: How did this transnational cooperation between riders’ collectives around Europe get started?

CP: The alliance among platform workers starts at local level, where different types of platform workers and their representatives work together daily in the Brussels context. Then, at national level, we have unions who contribute to make links between workers in different cities, something that local collectives are not always able to do, as they are composed of volunteers.

At European level, it gets more interesting: there has been the impulse of the Transnational Forum on Alternatives to Uberisation organised by The Left in the European Parliament, which allowed riders from all over Europe to meet and to realise that they share working conditions and claims.

We have also the work of the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), which every year brings together unions and collectives for the Trade Union Platfor(u)m, where we can exchange knowledge and practices. For example, in the last Platfor(u)m in Madrid, the crucial theme of the protection of undocumented workers was discussed in connection to the EU Platform Work Directive: the presumption of employment cannot turn against undocumented workers. Member States must verify the legal status of riders and platform workers, without contributing to a politics of deportation: to do this, it is necessary to dissociate the work of the labour inspectorate from identity checks made by the police.

READ MORE: Los riders sin papeles: Migrants tell their story from undocumented food delivery couriers to trade union organisers

There are also other initiatives, for example the one led by Brahim Ben Ali [General Secretary of the INV union in France which represents Uber drivers] who is trying to make international coalitions across drivers’ collectives: as riders in Brussels, we joined the drivers’ international mobilisation organised on 30 May to block Uber’s HQs in five European countries, in order to force them to put in place a real dialogue with platform workers’ representatives, both drivers and riders.

After the mobilisation, we saw in Brussels a good number of riders who saw their account re-activated, proving that it is essential to establish a more equitable balance of power between platforms and workers, with the objective of improving working conditions. This is not only about unfair deactivation of workers’ accounts, but also about fair remuneration: currently, we see that most platform workers are paid below minimum wage, and this is simply unacceptable.

The Gig Economy Project is a BRAVE NEW EUROPE media network for gig workers in Europe. Click here to find out more and click here to get the weekly newsletter.

Be the first to comment