Facebook’s impending new currency, Libra, could facilitate criminal exploitation of the payments system, while reducing the authorities’ ability to monitor and mitigate systemic risk. This article is part of a VoxEU debate on the future of digital money.

Stephen Cecchetti is the Rosen Family Chair in International Finance, Brandeis International Business School and Kim Schoenholtz is Henry Kaufman Professor of the History of Financial Institutions and Markets, NYU Stern School of Business

Cross-posted from VoxEU

On 18 June, Facebook announced plans to issue its own currency. By giving every individual with a smart phone the ability to purchase tokens in their own domestic currency, Libra would improve the efficiency of payments, reduce costs, and expand financial access—or so Facebook argues. This column, part of a VoxEU debate on the future of digital money, suggests the opposite: that Libra could facilitate criminal exploitation of the payments system while reducing the authorities’ ability to monitor and mitigate systemic risk. Financial regulators and central banks must act quickly and decisively to keep evolving financial technologies from threatening global financial stability.

“I just think it cannot go forward without there being broad satisfaction with the way the company has addressed money laundering…data protection, consumer privacy….” FRB Chairman Jerome H. Powell, Testimony to House Financial Services Committee, 10 July 2019.

“We have an open mind, but not an open door”. Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, 18 June 2019.

“A wider use of new types of crypto-assets for retail payment purposes would warrant close scrutiny by authorities to ensure that they are subject to high standards of regulation”. Letter to G20 Leaders, Financial Stability Board (FSB) Chair and Federal Reserve Board (FRB) Vice Chair Randal K. Quarles, 24 June 2019.

Facebook’s 18 June 2019 announcement that it has created a Geneva-based entity with plans to issue a currency called Libra sent shock waves through the financial world. Key central bank regulators such as FRB Chairman Jerome Powell warned against a “sprint to implementation” (see above).

Libra’s stated objectives include improving the efficiency of payments, reducing costs, speeding transfers, and expanding financial access. While these are laudable goals, it is important to achieve them without facilitating criminal exploitation of the payments system or hampering the ability of authorities to monitor and mitigate systemic risk. In addition, any broad-based financial innovation should facilitate the stabilization of consumption.

On all of these criteria, we see Libra as doing more harm than good. Libra looks to be Facebook’s third entry into the payments world, the first two—Credits and Messenger—were wound down or scaled back (BBC News 2012, Lunden 2019). The third time appears to be anything but a charm: Libra could facilitate various criminal uses of finance as well as become a significant source of systemic risk. For those who use it in advanced economies, Libra will likely add uncertainty to the purchasing power of savings, raising the volatility of household consumption. For the countries whose currencies are not a part of the Libra portfolio, its use will diminish seignorage and encourage capital outflows while accelerating capital flight in periods of stress.

Like Governor Carney, we maintain an open mind, believing that increased competition coupled with the introduction of new technologies will eventually lower stubbornly high transaction costs, improving the quality of financial services globally. But in this case, we urge a closed door.

Libra is a call-to-action for the official community. Financial regulators and central banks must act quickly and decisively to ensure that evolving financial technologies exert a positive force rather than posing a threat to basic values and financial stability. We hope that the FSB will follow through aggressively on the “close scrutiny” that Chairman Quarles espoused.

Faster, cheaper and safer?

Libra’s animating idea is that every individual with a smart phone will be able to purchase tokens using their own domestic currency. The Libra Association (a Geneva-based company) will invest proceeds from the sale of those tokens in a portfolio of bonds and bank deposits denominated in (what we assume to be) a few major currencies. Owners can then use their tokens to purchase goods and services, or to extinguish debts. If this occurs on the Facebook platform, with 2.4 billion users worldwide, it will become a mechanism allowing roughly half of the world’s adult population to transact directly.

Will Libra really make payments faster, cheaper, and safer, both domestically and internationally? Until recently, a combination of monopoly power and regulatory barriers made payments slow and expensive (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2017b). The entry of specialized companies such as Venmoand Square, and the response of incumbent banks—creating transfer systems like Zelle—are cutting costs and speeding small payments. As far as we can tell, most residents of advanced economies already have access to low-cost payments technologies (like bank debit cards). Will Libra be cheaper?

For cross-border remittances, which often serve the least well-off members of a society, the price remains extremely high. As we have suggested (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2018a), the costs of guarding against criminal activity are probably a key factor. Less expensive systems like Transferwise or Paypal transfer funds from one bank account to another, relying on the banks’ compliance operations to “know your customer” and thwart money laundering and terrorist finance. That is, systems are cheap when someone else bears the high fixed costs of verifying that criminals are neither sending nor receiving funds. Libra will surely require the same licenses and compliance systems as existing providers.1 Will Libra be cheaper?

Similarly, we strongly support the goal of improving financial access. At last count, there were 1.7 billion unbanked adults in the world (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2018a). Bringing them into the financial system will yield large economic and social benefits as well as improve services for the underbanked. Consider, for example, the amazing progress in India, where more than 350 million people have obtained no-frills bank accounts over a period of less than five years (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2017c). The creation of these accounts and their increasing usage reflects government efforts to lower the costs of knowing your customer (Aadhaar requires everyone 15 years or older to obtain a 12-digit identification number tied to their biometric data), to subsidize basic access, and to shift from cash to electronic transfers. Can Libra do better?

Adding volatility to consumption

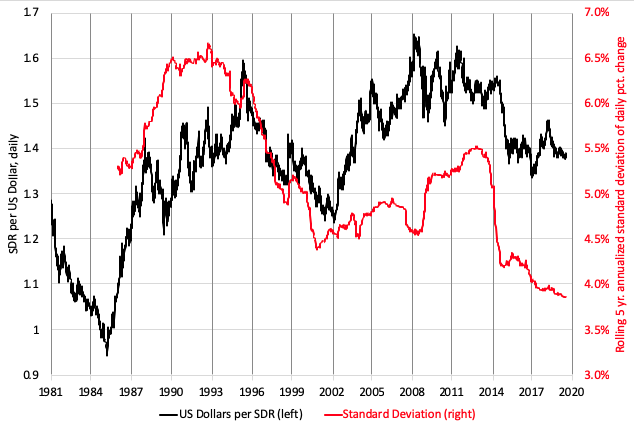

So far, so bad. It gets worse. Why would people living in a country whose policymakers have achieved price stability want to hold their savings in tokens whose value is pegged to that of a basket of currencies when the bulk of their purchases are made in their domestic currency? A key purpose of savings is to allow people to smooth their consumption, which requires stable purchasing power. But the value of Libra will move with the value of the currencies in its basket. To give some sense of how big such fluctuations might be, consider the case of the Special Drawing Right (SDR), the IMF’s reserve asset. An SDR is a weighted average of the US dollar, the euro, Japanese yen, British pound, and Chinese yuan (the last added in 2016). The following chart displays the US dollar value of the SDR (black line), as well as the five-year moving standard deviation of its annualized daily percentage change (red line). Note that even though the jurisdictions with currencies in the SDR enjoyed relatively low inflation, its dollar value has fluctuated between $0.95 and $1.65 since the mid-1990s, while the return’s standard deviation is between roughly 4 and 6½ percentage points.

Figure 1 Value of the SDR in US dollars (daily with rolling five-year standard deviation), 1981-July 2019

Source: IMF and authors’ calculations.

Why should law-abiding households and firms accept this added volatility in the purchasing power of their savings? If they understood the risks, they probably would not. The incentive to use Libra would be far greater in economies where purchasing power is less stable. Still, we argue below that the governments in these jurisdictions neither would nor should allow domestic use of Libra.2

Systemic risk

Perhaps most important, were it to be successful, Libra seems very likely to become a source of systemic risk for the global financial system. First, if Libra (on Facebook or WhatsApp) replaced a significant fraction of the existing payments system, then its failure would be catastrophic for those relying on it. Second, if the Libra Association guarantees convertibility into a national currency, then the Libra Reserve will operate as an open-end mutual fund (where the Association investors, not holders of Libra tokens, receive interest). The current proposal stipulates that the fund’s assets will be liquid government securities and bank deposits, with the Association settling the details. Like any open-end fund, it will be subject to runs on any less-liquid assets, such as bank deposits (Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2017a). Furthermore, the Libra Association could have significant bargaining power in obtaining higher deposit rates (especially from banks dependent on short-term wholesale finance). The more the Libra reserve invests in bank deposits, the more a Libra run would become a global bank run. Were the reserve to accumulate $1 trillion in assets—roughly the average of one of the top ten US bank holding companies—a run would precipitate a fire sale with global consequences. We need fewer, not more, structures like Libra.

Loss of seignorage and monetary control

Finally, we have three reasons to believe that it would be unwise for any country whose currency is not in the Libra basket to allow its citizens to use the new currency. First, the shift from domestic currency to Libra would reduce the government’s seignorage revenue, damaging public finances. Second, if domestic residents are transacting in Libra, the central bank risks losing control of the country’s monetary and payments system, making it difficult to maintain price stability. And third, acquiring Libra rather than a domestic asset constitutes a capital outflow, which seems likely to increase interest rates and reduce domestic investment. Libra could also become a vehicle for capital flight and a currency attack if people lose confidence in a country’s government finances or its financial system more generally.

Behind the fintech mask

We doubt anyone really knows where this is going. What we do know is that Libra is fundamentally different from cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. First, its backing will have fundamental value. Second, as the designers of Libra clearly state, the technology does not yet exist to make Libra permissionless (like Bitcoin) while still being useful for speeding billions of payments: permissionless systems are limited in what they can do (as we discuss in Cecchetti and Schoenholtz 2018b). Third, a consortium of for-profit companies, not a haphazard group of independent miners, controls Libra. Absent strong regulation, what incentive will this group have to protect customer identities, prevent misuse by criminals, and internalize its impact on the financial system as a whole? Why should we trust Facebook and its collaborators with such critical tasks?

While we may not know what Libra will become, we do know that it is not merely a mechanism for taking advantage of Facebook’s enormous platform to facilitate transactions domestically and cross-border. If Facebook believed that its platform could speed and lower the costs of exchange, in line with the hopes for Big Tech, then it could (like nonbanks Square, Venmo, and Transferwise) simply partner with traditional banks around the world (Bank for International Settlements 2019). Such a straightforward approach would exploit the comparative advantage of the two businesses, bringing together the network externalities of Facebook’s platform and the banks’ high-fixed-cost compliance and regulatory systems. There would be no need to introduce a new currency for this purpose. The lack of an effective, permissionless technology would be no obstacle, and there would very little regulatory uncertainty.

Regulatory and monetary control imperatives

That brings us back to regulation, and the need for action. Regulators will have to decide how to treat Libra and how to ensure that the approach is consistent across jurisdictions. Their choices will undoubtedly set the precedent for future Big Tech entries in the payments space, so the goal must be to promote innovation that strengthens competition and lowers costs without expanding threats to the financial system or compromising basic values.

Based on its economic function, Libra is one of three things: a bank deposit, a mutual fund, or a form of e-money (like M-Pesa), none of which pays a yield. If it is a bank deposit, then the Libra Association needs a banking license and must abide by banking laws in all jurisdictions where it operates. This would mean everything from capital and liquidity regulation to anti-money laundering systems and resolution planning. If it is a mutual fund, then the Libra Association would need to comply with asset management regulations and licensing requirements. If it were to become so large as to be systemic, then it would be subject to the strict scrutiny applied to such entities. If it is e-money, the Libra Association will need the approval of the financial services regulators who monitor payments-system compliance and the central bank charged with ensuring the effectiveness of domestic monetary control in every jurisdiction where it is used. In Kenya, the home of M-Pesa, some policymakers now wish to compel mobile money firms to become banks (Business Daily 2019).

The creation of Libra presents a variety of issues beyond those we have listed. What would happen to central bank balance sheets and to money multipliers if Libra led to withdrawals from the domestic banking system? What would be its impact on sovereign bond markets? The list goes on.

Perhaps the ultimate challenge Libra poses comes from the fact that it aspires to operate across multiple jurisdictions without a true “home.” For the most part, payments systems are set up to handle domestic institutions operating within national boundaries. We regulate these institutions using primarily domestic laws, with voluntary cooperation across borders. Even “global” banks have a home supervisor examining them on a consolidated basis. The prospect of Libra serves to dramatize the existing asymmetry between this largely domestic approach and the rise of global, multi-jurisdictional entities capable of choosing any home temporarily and shifting at will.

The bottom line is this: Facebook’s proposed creation of Libra is a wake-up call. It makes inescapable the need for rapid, international coordination of financial regulation. Without mechanisms to ensure consistent application of coherent global rules, we may find ourselves in a world of “low-quality finance havens” that exist to evade financial regulations—not unlike the “tax havens” that already exist merely to evade taxes.

Authors’ note: We thank our friend and NYU Stern colleague, Hanna Halaburda, for her very helpful suggestions. An earlier version of this column appeared on www.moneyandbanking.com.

Be the first to comment