The IMF and its academic acolytes want more austerity and privatisation, ignoring the fact that these ‘good policies’ are what got us here.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger.

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts’ blog

In 2019, economics professor Gita Gopinath left the halls of Harvard University to become the chief economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Three years later, she made an unprecedented jump from economic analysis to policy management, becoming the first ever ‘deputy managing director’ — or the IMF’s effective number two – the right-hand (woman) of IMF managing director, Kristalina Georgieva. Last Friday, she left to return to academia at Harvard.

Gopinath is the epitomy of a modern mainstream economist (here is her CV). A firm believer in the capitalist system ie. economies owned and controlled by privately owned companies (mainly large but also small) that produce,invest and employ to the degree that profits are made by the owners (directors and shareholders). But within the arena of capitalism, Gopinath naturally wants to make capitalism work for all globally. She is aware of capitalism’s ‘imperfections’ and sees her role as analysing those to develop policies that can keep the ship of capitalism stable as it moves through dangerous waters.

She was interviewed by the Financial Times on the storms facing capitalism during her six years at the IMF. When Gopinath looks back, she told the FT: “2019 feels like the calm before the storm. We’ve had now multiple years of big tectonic shifts – the pandemic, war in Ukraine, the energy and cost-of-living crises, and a rise in geo-economic fragmentation.”

But Gopinath remains confident in the system: “what has been very surprising in a good way is that despite these major shocks, the global economy has been resilient.” And why is that? “In my view, the number one reason for that is that there have been good policies that have helped. The fact that they prevented a financial crisis has been critical. Because if we look at history and you see downturns or crises that have very long-lasting effects and large amounts of scarring, they’ve usually come after a big financial crisis. The fact that we’ve gone through a pandemic, war, the Federal Reserve raising interest rates sharply to fight inflation, geo-economic fragmentation, but we still haven’t seen a financial crisis, is very important to why we have not had much bigger hits to the global economy.”

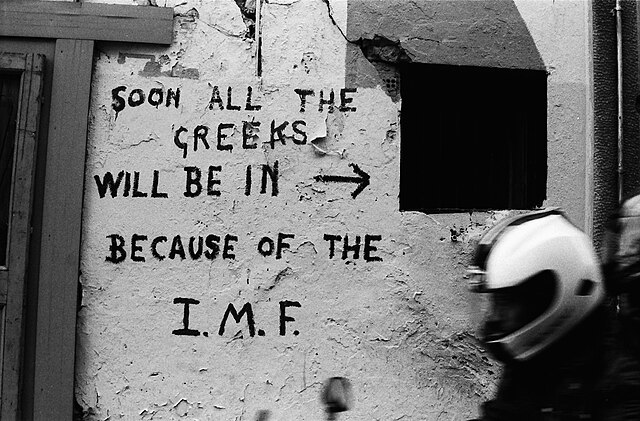

Hmm… the global capitalist economy may have been ‘resilient’, in so far that there has been no financial crisis since the global financial crash of 2008, but hardly in any other criteria. The pandemic slump was the deepest (if short-lived) and widest in global impact in the history of capitalism, with virtually all the world’s economies suffering a significant downturn in national output. Gopinath sees the pandemic slump and the subsequent post-pandemic inflationary spike as ‘shocks’ that had to be ‘managed’, not as endemic recurring crises generated by capitalism itself. But there is plenty of evidence that the major economies were heading into a slump in 2019 even before the COVID pandemic erupted (and that pandemic could have been avoided if big pharma had not been deciding what vaccinations and medicines were profitable to develop and if governments had not decimated health systems with the policies of fiscal austerity).

There were permanent scars from the pandemic left on economies and on the living standards of most people globally. The pandemic slump increased global poverty levels (already high) to new heights – as another 700m fell below the World Bank’s miserably low poverty benchmark. And then the IMF and major central banks failed to spot the huge inflationary spike after the end of the pandemic caused by the disruption of global supply chains, energy company price hikes and the loss of workers in key industries. The answer of the IMF and the central banks was to hike interest rates because they (and Gopinath) thought that inflation is caused by ‘excessive demand’ or ‘excessive wage increases’. The result was a 25% rise in average prices in the major economies over the next three years to 2023, a rise that remains locked into the cost of living for most households.

In the interview, Gopinath claims that central bank independence generally “is one of the crown jewels of good economic policy” because “independent monetary policymaking has been critical to ensuring price stability. It was critical to bringing inflation down after the post-pandemic surge without a big sacrifice in employment. The anchoring of inflation expectations was absolutely critical to that. And so I think that is a lesson we have to take away.” Here, Gopinath repeats the mainstream mantra of central bank independence (CBI) as the reason for controlling inflation and yet there is little compelling evidence for this – CBI is really protection for the financial sector from interference by governments.

Again there is no evidence that central bank ‘anchoring of inflation expectations’ brought inflation under control. Inflation rocketed post-pandemic under Gopinath’s watch and slowed later when global supply and employment recovered, not because of central banks ‘anchoring inflation expectations’. As a paper by Jeremy Rudd at the Federal Reserve concluded: “Economists and economic policymakers believe that households’ and firms’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. A review of the relevant theoretical and empirical literature suggests that this belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors.”

If ‘resilience’ means more than avoiding a financial crash, then the major economies have not been resllient at all. The rate of real GDP expansion since 2021 has been pathetic. The US economy is growing at about 2% a year in real terms, even lower than in the long depression years of the 2010s, but even that is better than the rest of the top G7 economies, which have stagnated with average growth rates of less than 1% a year at best. Even world economic growth (including the fast-growing large economies of India and China and non-Japan east Asia) is dropping.

Here is the World Bank view. “This year alone, our forecasts indicate the upheaval will slice nearly half a percentage point off the global GDP growth rate that had been expected at the start of the year, cutting it to 2.3 percent. That’s the weakest performance in 17 years, outside of outright global recessions… By 2027, global GDP growth is expected to average just 2.5 percent in the 2020s—the slowest pace of any decade since the 1960s.” The World Bank continues: “By 2027, the per capita GDP of high-income economies will be roughly where it had been expected to be before the COVID-19 pandemic,” (some seven years since the pandemic). “But developing economies would be worse off, with per capita GDP levels still 6 percent lower. Except for China, it could take these economies about two decades to recoup the economic losses of the 2020s.”

Gopinath says in the interview that “good policies avoided a financial crisis”. Presumably she refers here to central bank monetary injections and fiscal spending by governments during the pandemic to sustain businesses and households. However, the result of all these ‘good policies’ that staved off a financial crisis by bailing out the banks (again) and large companies is that “global [public debt] levels are now incredibly high. In 2024, they were around 92 per cent of global GDP. And as a reference, that number was 65 per cent in 2000. So there has been a very substantial increase in global debt. But even more concerning, the projection is for it to continue to increase and hit 100 per cent of global GDP in 2030.” (Gopinath). Gopinath fails to tell the FT that, in the advanced economies, the public debt ratio is even higher, at 110% of GDP this year (with the US at 125%). But she admits that the IMF’s own forecasts of the rise in public debt to GDP were too optimistic. “Ultimately debt-to-GDP is about 10 percentage points or more higher than what we projected. So this is a serious issue countries will have to grapple with.”

In the FT interview, Gopinath does not say why public debt has risen so much. And yet there are some obvious causes. “There is an imbalance between what is expected of the state in terms of spending and what is actually possible given the revenues being collected.” No kidding, but which is the problem: revenues or spending? The main reasons were the bailouts of the banking system in the global financial crash of 2008; the slump in the Great Recession reducing tax revenues and increasing social spending; and a similar repeat in the pandemic slump of 2020. So the public debt ratio has risen because governments borrowed more and national output growth slowed. But government borrowing also increased despite years of fiscal austerity (spending cuts) in the 2010s because tax revenues did not rise sufficiently. Governments reduced corporate profit tax rates, companies shifted their profits into tax havens, and companies and rich individuals used various tax avoidance schemes or just did not pay (huge amounts of taxes remain unpaid and uncollected).

The IMF, the World Bank, the OECD and governments talk about closing down tax havens and avoidance schemes – but nothing ever happens. Meanwhile, the World Bank has presented a dismal picture of the situation for most people in the world. In 2024,“Global extreme poverty reduction has slowed to a near standstill, with 2020-30 set to be a lost decade.” Around 3.5 billion people live on less than $6.85 a day, the poverty line more relevant for middle-income countries, which are home to three-quarters of the world’s population. “Without drastic action, it could take decades to eradicate extreme poverty and more than a century to eliminate poverty as it is defined for nearly half of the world.”

The other striking omission in the interview is that Gopinath makes no mention of global warming and climate change. When she joined the IMF in 2019, there were many IMF studies on emissions mitigation, funding for renewables, and carbon pricing and taxes. Now as multi-nationals and banks have ditched all their climate policies to boost profits, the IMF is more or less silent. It is no accident that Gopinath ignores this literally burning issue for the world.

In the interview, Gopinath is more worried about the rise in public debt ratios (she seems to see this as the major problem, not what is happening with inequality, poverty or the climate). She is worried that the cost of borrowing by governments (in the West) and for companies and households will rise. Everywhere the interest costs on government debt are rising and many poor countries pay more in interest on their debts than they spend on health and education). The US government is facing a massive increase in interest costs on its burgeoning debt, especially if interest rates stay above inflation rates.

Gopinath says the problem is that “We do not have a global savings glut anymore. We do not have central banks buying large amounts of government debt. And we are seeing long-term yields . . . now back to pre-global financial crisis levels, and term premia have gone up. So that’s a second area where I think, compared to 2019.” But there never was a ‘global savings glut’. I and others have refuted this theory on several occasions. The problem was not too much savings, but too little productive investment to drive economic growth.

What Gopinath really means is that countries like the US and the UK are running twin deficits on government budgets and trade which have to be financed. Foreigners are less willing to buy the US or UK debt and their central banks are selling their holdings (quantitative tightening) and no longer buying the debt (quantitative easing). Given that inflation rates remain stubbornly higher than forecast, everywhere government bond yields are rising. So according to Gopinath, “We are certainly at a moment where, given the large amounts of government debt, the growth of non-bank financial institutions and questions about central bank independence, we could certainly push ourselves into . . . a global financial crisis. That would be something that would not be easy to recover from for the world.” It seems that the previous ‘resilience’ of capitalism in the last six years is about to crack, after all.

So what’s Gopinath’s policy answer after six years at the IMF: fiscal austerity and ‘structural reform’. Governments need to “rebuild fiscal buffers” which “will involve less spending and taking a very close look at entitlement spending, including on healthcare and social security” (!) (Even the FT interviewer recognised that Gopinath was advocating that spending “demands have to be brought into alignment with revenues rather than the other way round.”)

Actually the emphasis by Gopinath on rising public debt as the potential cause of a future financial crash is misguided. Public debt ratios have only risen because of the failure of the private sector to sustain sufficient economic growth and avoid too much borrowing. The average profitability of capital has fallen since its peak at the end of the 20th century and has stayed at low levels since 2019. Yes, a small number of huge tech and energy companies have made mega profits, but most companies in the US, UK and Europe have struggled – indeed, as mentioned many times before, some 20% or more companies in the major economies make no profit and are forced to borrow more to keep going. Behind the scenes, behind the banks, ‘shadow’ banks (private lenders) are propping up swathes of ‘zombie’ companies. This is where the risk of a financial crash is highest – not in public sector debt.

Gopinath is also worried about ‘global fragmentation’ – this is IMF-speak for the end of globalisation and ‘free trade’ that the world economy has experienced in the last six years (and before). She is concerned that the “the US will want to decouple from the rest of the world as that would be very costly. It is simply not possible to stop trading with the world without also ending [inflows of] finance from the rest of the world, or ending dollar dominance.” So we need to sustain all the good things of the last 40 years: free trade, free flows of capital and US dollar hegemony. “I take it as a positive sign that there is still, in many international discussions and platforms, strong support for open trade. I would expect trade to continue, but a lot will depend on making sure that domestic sentiment also aligns with keeping borders open.”

Gopinath says she has spent some time and research into the impact of AI. She reckons that about 40 per cent of the global labour force is exposed to AI. In a paper last yearshe argued AI could worsen any future slumps by expanding the range of jobs subject to automation, “which businesses are more keen on when times are tough.” But don’t worry, “on the positive side: good policies that were championed by the economics profession and policy institutions — independent monitoring, financial supervision and regulation, timely fiscal support — all of that has delivered a global economy that is resilient to big shocks.”

Really? If so, then the general public seems ungrateful for the ‘good policies’ suggested by the IMF and the mainstream economics profession – and followed slavishly by centrist and social democratic governments for decades . As Gopinath admits, these “good policies of trade integration, central bank independence and fiscal prudence” of which “there was broad consensus in the profession” seem to “have generated some kind of a trust deficit with the economics profession.” There“have been blind spots” in economic analysis, so trust in mainstream economics is “not something we can take for granted, as we might have done in the past.” Indeed. Anyway, Gita Gopinath is going back to academia to train a new generation of economists in those ‘good policies’.

Be the first to comment