In the corona crisis the EU is failing at every opportunity, economic and political.

Annamaria Simonazzi is Professor of Economics, Sapienza University of Rome

Cross-posted from the Institute for New Economic Thinking

What did the European Council meeting of April 23rd achieve?

The answer is – not much. It set up a new Troika – the European Stability Mechanism, SURE (or “Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency”), and the European Investment Bank – providing loans worth 540 billion euros, (of which approximately 54b. for Italy). The size of the “rescue package” is risible even when compared with the Italian effort, which is, in turn, minuscule compared to Germany’s. They are loans, whose conditionality and maturity are kept vague. Moreover, there is a proposal for a Recovery Fund, of which nothing is known. Neither its size, nor its timing, linked to the EU’s upcoming Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), and based on member states’ contributions, to be increased from 1 to 2%. Acute disagreement over the proportion between grants and loans divides the countries’ representatives, often on arguments defined “repulsive” and “senseless” by one participant.

What we have so far seen is mere window dressing. Meeting after meeting, the image that is perceived by a struggling population is of a governing class totally unaware of the dramatic urgency of the situation. In two months nothing came of it, in terms of concrete measures, apart from apologies for the inaction. But, to paraphrase the title of a song by a famous Italian chansonnier: If only I could eat an apology. When, and if, anything does come of it, it will be too little, and dramatically too late. It’s a matter of near-term survival: locked-down firms will not reopen, furloughed workers won’t have jobs to go back to.

In the total absence of the EU, countries are left alone to cope with the disruption of their economies. The huge differences between member states’ fiscal situations mean an enormous difference in their ability to intervene. The data on fiscal measures change rapidly, but according to IMF data as of April 23, direct intervention in Germany corresponded to 4.9% of the GDP, compared with 1.4 for Italy and 1.6 for Spain, not to mention the gap in state guarantees for business to access liquidity.

We are left with the European Central Bank (ECB). It has changed its rules to accept as collateral assets with credit ratings below investment grade. It has lifted the self-imposed limits on the share of public securities it is prepared to buy, allowing temporary deviations from the capital key and limits to each issue. Under its old and new programmes (QE and Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme, PEPP, launched on March 8th) in 2020 the ECB could purchase 1.1 trillion euros worth of securities (7% of the Eurozone GDP); 10% of the Italian public debt (€ 160- 180 billion), besides rolling over €350 billion worth of securities.

All well, then? Not really. As stressed by The Economist, the ECB is the outlier among its peers: the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan and Bank of England are doing much more. And Christine Lagarde pledged to do even more if needed. However, ECB intervention is discretionary. It’s up to the ECB whether to intervene or not, and past experience has shown how its choice can affect economic and political developments in the various countries. “Technical” decisions can affect spreads, agency ratings, refinancing conditions, the sustainability of the debt, and indeed the fate of governments. Threats can thus be very effective, as demonstrated by its handling of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) in the Irish and Greek crises. Finally, by stalling the crisis, the ECB provides the governments with an excuse for inaction.

These considerations are important to understand the climate in the southern countries and the widespread disillusion with the European dream.

What are the merits of the different proposals on the table?

Flimsy as it was, the Recovery Bond proposal had the effect of burying any discussion over alternative solutions (such as Eurobonds or Coronabonds). No consideration was paid to the possibility that, by restoring confidence in the continuity of the EMU projects, a “whatever it takes” from the Eurogroup, and the provision of a safe asset (other than the Bund), might have mobilised domestic savings, thus contributing to alleviate the financing problems in debtor countries. The stance was: no mutualisation, period. Thus, there are no other proposals on the table.

There are several suggestions off the table, though, and they are taking worries over the sustainability of the European project seriously, tackling the issues of size, maturity and conditionality. Academics are by now almost unanimous in favouring some kind of monetization: issuance of perpetuities (consols) or very long term bonds, backed by the ECB , or bought by the ECB in the primary market, and buried for good in its coffers.

Any proposal has to face the fact that piling loans on stricken countries risks causing a new sovereign debt crisis as well as permanent indentured servitude. Italy is the third largest public bond market in the world. There is a concrete risk of disintegration, and there should be a general interest in avoiding it. Exit from the crisis should be dealt with not as a matter of “solidarity”, but of self-interest. As Wolfgang Münchau put it: collective action should be seen as “insurance risk” against default.

Intervention is dramatically urgent now, because, as also stressed by the former governor of the Dutch Central Bank, Nout Wellink, in a month’s time it will be too late, economically and politically. There is a need for income support for households, and credits and subsidies for businesses, now. Many firms won’t be able to survive anyhow, which means that in the medium term we shall need to intervene again to avoid a new, more severe phase of debt deflation. It seems to me that our EU governors are unaware of just how destructive the current situation is.

What will the recovery of the EU economy be like?

It depends. If coping with the crisis is left to national policies, with only the ECB left trying to keep the euro from disintegrating, divergence can only accelerate. Lacking adequate support, struggling businesses in the southern countries will disappear, the destruction of productive capacity will produce cumulative effects on the budget deficits (a disaster film that we had already seen in the previous crisis).

With an even more impoverished South, and international conditions radically changed, it is doubtful that the frugal North will prosper. This is all too clear to many industrial and financial interests in the North (and perhaps also to Ms. Merkel). The game that we had already seen in the previous crisis, waiting to reach the cliff edge before taking action, is extremely risky in the current situation.

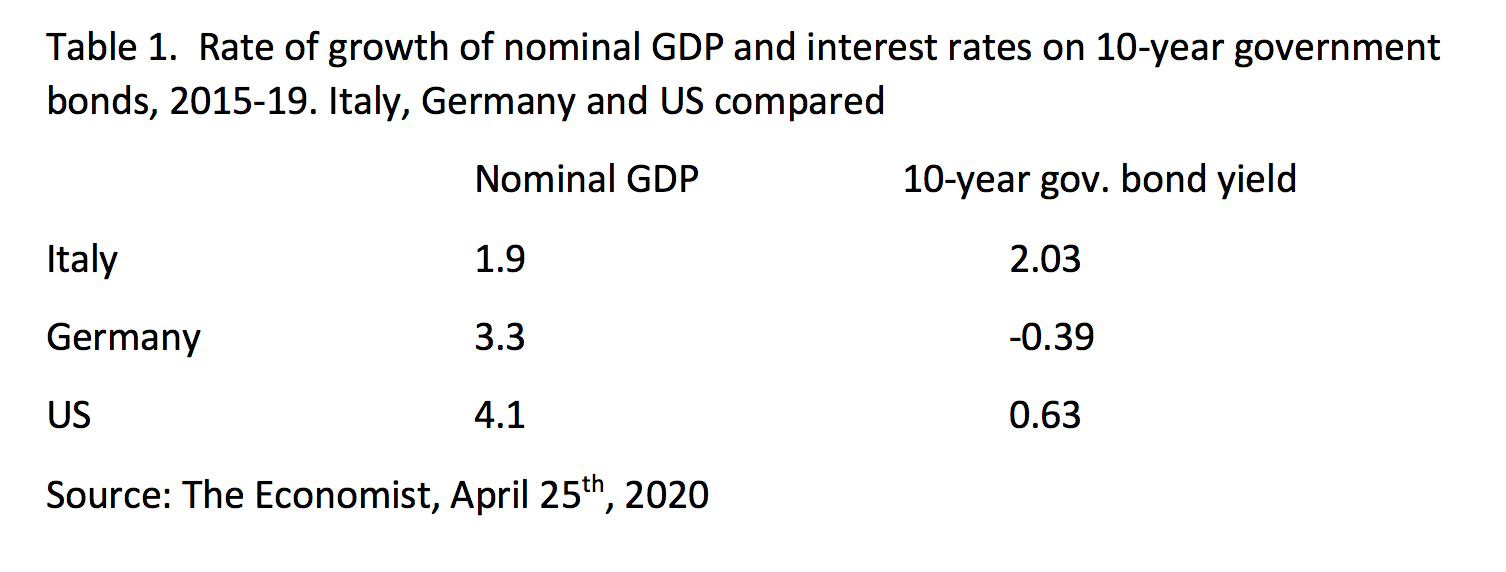

In any case, the solution cannot be returning to the pre-coronavirus situation. Divergence was underway before the pandemic. Structural problems cannot be solved with austerity or market policies . Very long maturities and low interest rates, though necessary, will not help if the GDP growth rate does not increase (table 1). Restoration of the old fiscal rules would hardly go down very well, even with pro-Europe governments since, as Abraham Lincoln put it, “you cannot fool all the people all the time”.

How concerned should we be about the political fall-out from EU policy responses?

Europe is now deeply divided. Recrimination is rife in creditor and debtor countries alike, fuelled by many misconceptions. There is a mistaken belief, prevalent in the North, about the spendthrift South. Italy has been running primary surpluses for 30 years, since the 1990s, with the one exception of 2009. It entered the EMU with a huge public debt, but its GDP ratio kept falling slowly to just below 100% immediately before the 2008 crisis. It is true that the rate of tax evasion is high but, on this point, nobody is perfect. We have, within the common market, tax havens and countries competing via subsidies and low wages. And not only do these distortions hit some countries harder than others, but while firms take their profits to and pay their taxes (so to speak) in tax haven countries, it is the countries where they produce that have to disburse the unemployment subsidies in a crisis.

There is another misconception over the refrain: “no more transfers”. When were these transfers made, if we may ask? Greece has been stripped to the bone, first to save French and German banks, and subsequently it was dispossessed of its airports, harbours and firms, bought at bargain prices.

Austerity meant low growth, low wages, cuts in services, increasing and widespread precariousness, and youth migration. It caused impoverishment, greater inequalities, anxiety and popular resentment. The absence of Europe in the various crises – financial and economic in 2008, immigration, coronavirus – has turned the population against the EU.

A change in mind-set is necessary and urgent. And it seems that, in this crisis, more people in the North may be disposed towards a greater degree of solidarity than their governors have been able to perceive. We must act quickly, before things deteriorate to the point of no return.

Be the first to comment