Why is capital so concentrated and why so few have it?

Branko Milanović is an economist specialised in development and inequality. His newest book is “Capitalism, Alone: The Future of the System That Rules the World”. His new book, The Visions of inequality, was published October 10, 2023.

Cross-posted from Branko Milanović’s Substack

This is the third (and presently the final) installment of my short essays on new capitalism. This essay deals with income from ownership of productive and financial assets that for simplicity I shall call “income from capital”. There are three important things to know about capital income under new capitalism.

1. Capital income is not the same thing as labor income. At first it seems obvious. And it should be. Labor income, to be made, requires exertion and effort: being at the work place or at your online location; it requires concentration, thinking, physical effort (try doing the delivery job of an Amazon driver for a change, let alone of a coal-miner). Capital income requires none of these things. It requires only that you bring your suitcase stuffed with cash to the bank or ask your banker to move your money from a savings account to an investment fund. That’s all.

Now, that fundamental difference has implications that are intentionally overlooked by neoclassical economists. $100 received out of labor is not a net, but gross, wage. Because working involves disutility. (It is bizarre to remind of that fact neoclassical economists whose whole world, including the supply curve of labor, is based on utility; but here, suddenly, they forget all about it.) One should therefore deduct the compensation for mental and physical effort needed to earn these $100, and only the remainder should be treated as net value added in national accounts. This is equivalent to the fact that the depreciation of capital is not considered net value added. But labor economists have somehow forgotten to do that.

Not only does it have an impact on how value added and thus GDP should be calculated but it has an impact on how taxable income is defined. Take a person on a very low wage. His entire wage is taxable while in truth only a portion of his wage represents net income (in excess of labor power depreciation) and only that part should be taxed. For low-wage workers net wage is therefore very small. Perhaps 50% or perhaps even 80% of it is simply supposed to bring our Amazon delivery driver, or coal-miner, back to the state of satisfaction or “full stomach” and rest where he was before his working day started. For much better-paid workers, the “depreciation” part is almost certainly smaller (in relative terms), and thus, in reality, net wage differentiation is much greater than it appears from gross wages. Moreover, taxation is heavily skewed against low-paid labor. None of these issues appear with capital income because capital income is considered in its net form, as profits out of which interest and dividend are paid, that is, after depreciation is deducted.

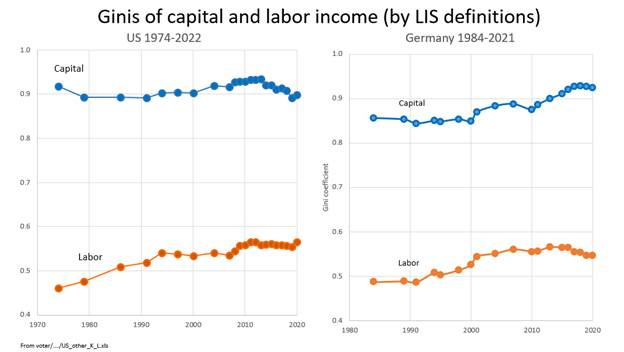

2. Income from capital is much more concentrated than income from labor. Figure below is a typical result you get when looking at the concentration (Gini coefficient) of capital and labor in advanced capitalist economies. When you rank people from the those with the lowest wage (including zero wage) to the highest, you generally get a Gini coefficient of around 0.55-0.6 (red line). Note, for example, that the US and Germany are not very different in terms of inequality of wage distribution. (I show here only US and Germany, but the graph is almost identical for any rich country. ) But when you do the same thing with capital income—starting from the lowest and going to the highest—you get a Gini that is twice as high (blue line). Why?

Note: The graph shows Gini coefficients of labor and capital income. The latter is equal to interest, dividends and rents received.

First, and most importantly, because majority of people (and thus households) have no income from capital. Yes, this is true; as we shall see below, more than one-half of households in rich Western economies receive zero income from financial assets. Second, those on the top of capital income distribution receive very, very high capital incomes and that also drives Gini up.

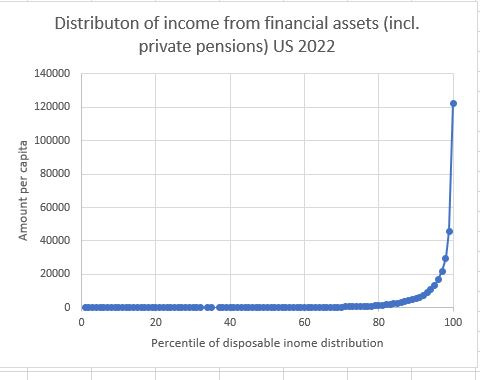

Take the most recent US 2022 data from the Current Population Survey (harmonized by LIS). When you display capital income distribution, from the lowest (on the left) to the highest (on the right), you get the figure below. Hockey-stick, big time!!

Note: The graph shows the average amount of capital income received by each percentile of the distribution (when people are ranked by their household per capita capital income). It shows that almost 80 percent of households have zero or close to zero income from financial property. Calculated from Luxembourg Income Study, based on US Current Population Survey.

Twenty-eight percent of US households have zero income from capital. 59% of households have de facto zero, or quasi-zero (trivial) income from capital. (I assume that trivial income from financial assets is one that is less than $100 per capita annually, i.e. less than $8.33 per person monthly.) As a curiosity, note that the median annual per capita income from financial and productive assets in the United States is $21.89. That would buy you a glass of Chardonnay in Manhattan, or perhaps three beers in Iowa. Thus, basically, 60% of households are, when it comes to capital income, zeros!

After that point, capital income becomes positive, and then toward the top of the distribution, it raises exponentially (as you can see in the graph) to reach some $122,000 per capita in the highest percentile. That amount, moreover, is underestimated because super capital-rich people are seldom included in surveys (they are objectively difficult to capture because there are so few of them and survey size is limited) and because people tend to underestimate their wealth and their capital income. But that still means that an average family of four in the highest US capital income percentile receives about half-a-million US dollars annually from financial property alone.

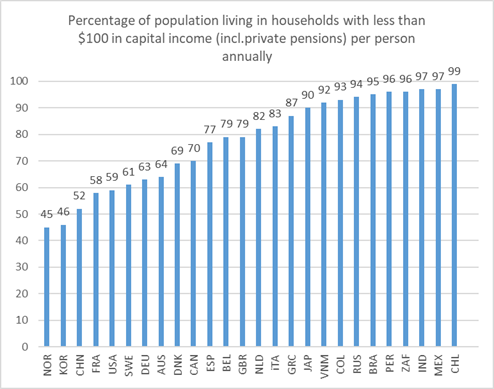

3. How many people in the world receive income from ownership of capital? We have seen that 60% of US households have zero or quasi-zero income from property. The situation is not different in other advanced economies: in Germany, that proportion is 64 percent, in Denmark 69 percent, in Great Britain 79 percent, in Italy 83 percent, in Greece 87 percent. The most “people capitalistic”, among the modern economies are Norway, South Korea, France, and…China.

In some countries like Norway and the UK private pensions (included in the graph below) do make a difference: for example, the percentage of zeros in the UK goes down from 84 to 79 percent when private pensions are included. Chile is also an interesting and rather extreme case. Only 20 percent of households have clear zero income from property. But 79 percent have trivial amounts (less than $100 per capita annually) received from the Chilean system of funded pensions. So, in reality, only 1 percent of Chilean households have practically all Chilean capital income! In most other countries, income from private pensions does not make much of a difference (partly because it is received by people who are non-zeros anyway) or funded private pensions are too small or do not exists.

Note: The graph shows the percentage of households with zero or almost zero annual income from capital. Calculated from Luxembourg Income Surveys; most data are for years 2020-2021.

When we move to less rich countries, the percentage od zeros and quasi-zeros becomes absolutely overwhelming and, yes, stunning. In Brazil, Peru, South Africa, India, Mexico, Chile… more that 95 percent of the population has no income from capital at all. Of course, that means that 5 percent or fewer of their populations garner the entire income from financial assets.

The data from LIS that I have put together include some 4.6 billion of people in the world. The data come entirely from rich, and upper-middle-income countries. Overall, the (population-weighted) share of population with zero capital income is 77 percent. The remaining 3.6 billion people for which I have not assembled the data (yet) are all from much poorer countries in Latin America, South-East Asia and especially in Africa. It is very likely (almost certain, I would say) that no more than 5 percent of people living in these countries have financial-sector income. With 95% zeros from these countries and 77% of zeros from the rich and middle-income countries, we get an estimate that 85% of the people in the world are capital-income destitute.

In other words, the world’s financial and productive assets are owned by 15% of its inhabitants (households).

4. What does it all mean? The new capitalism has even in the rich countries failed to produce what Margaret Thatcher, and Friedrich Hayek before her, called “property-owning society”. (For good measure, Thatcher added “democracy” too.) Even when we include income from forced savings that becomes pension wealth, between one-half and almost 90 percent of the population in rich countries are capital destitute. That percentage becomes more than 90, or even more than 95, in less developed countries.

The two biggest countries in the world are interesting. Nominally, capitalist India leaves 97 percent of its population with zero capital income; nominally Communist China has become remarkably “capitalized” in the past forty years and about one-half of its population receives some income from capital; relatively more than in the United States and the UK.

To conclude: when it comes to capital ownership, new capitalism has not broken, in any significant way, the barrier erected by the classical capitalism: receiving income from capital is a privilege of the few and that privilege is, even amongst those who have non-zero income from capital, extraordinarily skewed.

The new capitalism is not people’s capitalism, but homoploutic capitalism. What has happened was not that capital income tricked down, but that labor income “trickled up” and combined with the pre-existing or newly-created large fortunes to create, at the very top, a new class whose wealth comes from both labor and capital. Homoploutia, or new aristocracy, my friend!

Be the first to comment