The main difference between Trump and the “traditional” neoliberals turns out to be their optimism or pessimism regarding durable control of government

Branko Milanović is an economist specialised in development and inequality. His new book, The Visions of inequality, was published October 10, 2023.

Cross-posted from Branko Milanović’s Substack

This photo is a work of an employee of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, taken or made as part of that person’s official duties. As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain.

Forget for the moment the fuss between Trump and the Fed that is going on now. Go back to the situation as it was six months ago and as existed for the last fifty years.

There was on one side a very large and important camp of neoliberals. As Quinn Slobodian documents in his excellent book Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (my review here) neoliberals, assembled in the Mont Pelerin society, were skeptical of the ability of pro-capitalist politicians to win elections and thus to control the levers of legislative and executive power. They feared, not unreasonably, that left-wing, socialist and populist parties would often do better and come to power. So, how can economic policy-making be saved from socialistic impulses of such parties? The solution was to gradually exempt many functions of the state from the oversight by the legislative and executive branches and transform them into purely technical agencies. If monetary and fiscal policies, and regulation of business etc. could be claimed to be technical matters best left to specialists, decision-making would be independent of the party in power and agencies would be able to maintain “correct” policies in the interest of capital-owners.

This was the ideology behind the independence of central banking, and likewise of other, economic, parts of government. In fact, the term “independence” here means independence from the elected officials who represent public interest. Neoliberals couched all of this, as Slobodian writes, into a distinction between “the dominium”, an area where economic power is held by professionals, and “the imperium”, an area where the elected officials exercise symbolic functions such as hoisting of national flags, celebrations of independence, or marching with the music bands but have no influence on policies that determine interest rates, taxation, regulation of businesses, movement of capital. All real business is to be done in the “dominium”.

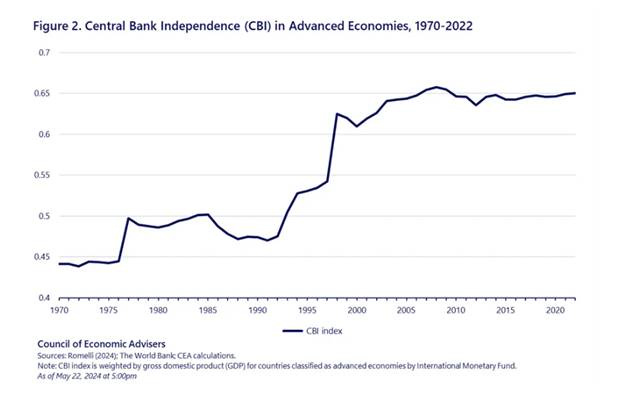

The approach became “internationalised” in the 1980s and 1990s. Led by the World Bank and the IMF, an increasing number of countries adopted “depolitization” of central banks, and, to a lesser extent, of other technical sectors of economic decision-making. The graph below which I took from Adam Tooze’s recent Substack shows a remarkable increase in central banks’ independence in rich countries between the end-1990s and (not surprisingly) the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. It was part and parcel of neoliberal globalization and was copied by many developing countries. Central bank independence became, in that view of the world, absolutely vital.

We may note, incidentally, that this approach is very similar to the current Chinese approach. The entire political sphere, it could be claimed (and was claimed by Tongdong Bai in his book Against Political Equality; my review here), is best left to technical management by highly-skilled professionals. It does need popular oversight. That oversight may only be detrimental to efficiency. We do not subject medical doctors’ decisions to popular vote. Likewise, highly complex economic and political matters are to be left to the educated and competent. The problem with the elected governments is precisely that they do not stay out of such decision-making, a problem aggravated when governments are elected by people who themselves are ignorant of economics and politics.

This neoliberal view had many detractors over the past half-century. Let’s call the camp of detractors the “democratic camp”. They argued that decisions on the economy are decisions that, in order to be legitimate, need the same electoral and democratic imprimatur as any other government’s decisions: legislatures can decide to increase or decrease the voting age as they can decide to increase or decrease the rate of interest. Economic matters should be under popular control even more that other matters because they impact all of the citizenry. If increasing number of issues are decided by the professional-managerial class what is the purpose of democracy and of elected officials? To lead people in the singing of national anthems?

That is how the two camps were arrayed.

Enter Trump. He wants to control the Fed. Does it make him join the democratic camp? Not at all. What he is doing is reinforcing the neoliberal agenda. To see this, recall how the independence of economic decision-making came to be part of the neoliberal agenda: because “traditional” neoliberals were pessimistic about the ability of like-minded conservative politicians and parties to win and keep political power. Advocating the independence of economic agencies was a way to prevent “bad” outcomes in case of unfriendly politicians coming to power.

But Trump is not a pessimistic and defensive neoliberal. He is an optimistic and aggressive neoliberal. If he today, and similar politicians tomorrow, hold political power, why shouldn’t they take over all economic institutions too? Mises and Hayek would have been approved—except that they were too skeptical about the ability of such politicians to remain in power. But Trump s not.

The main difference between Trump and the “traditional” neoliberals turns out to be their optimism or pessimism regarding durable control of government, not their view on whether neoliberals ought to control economic institutions. “Traditional” neoliberals were pessimists; Trump is an optimist. He is confident that neoliberals and MAGA will rule the world (and for sure, the US) for a while. If so, why shouldn’t they rule the Fed too?

Be the first to comment