Chris Saltmarsh, co-founder of Labour for a Green New Deal and post-graduate student in Politics at the University of Sheffield, analyses the various ideological conceptualisations of the Green New Deal.

This article is cross-posted from the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (Speri) blog.

Xhulia Likaj, Michael Jacobs & Thomas Fricke’s recent paper ‘Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate’provides a compelling conceptualisation of the contemporary growth debate as one between competing political strategies. What, then, of the Green New Deal? In recent years, the proposal has become a headline demand for progressives of all stripes. I argue that the Green New Deal (GND) acts as a point of strategic unity while also remaining a site of political contestation for those engaged in the capitalism-growth debate.

The GND can be loosely defined as a state-led economic mobilisation and policy programme with the dual aims of tackling climate change and social and economic injustices. After Thomas Friedman coined the phrase in 2007, the Green New Deal Group of economists in the UK developed the idea as a response to the 2008 crisis. It would be thrust into the mainstream a decade later by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Sunrise Movement in the US, and later adopted by the UK Labour Party following campaigning by party members.

After a flurry of interest over recent years, the GND is increasingly subject to criticism as insufficient, technocratic or poorly framed. In his book Scorched Earth, Jonathan Crary describes the GND as a market-driven scheme and therefore “absurdly pointless”. James Meadway criticises its impetus to impose transformation on people, rather than “something done with them”. In the Guardian, Aditya Chakrabortty argues that the project acts as a “conceptual fog”, obscuring disagreements to maintain temporary and unstable coalitions.

However, there is not one singular GND to speak of because it has been adopted by progressives of all kinds. Criticising market-driven GNDs should therefore come with recognition of those calling for sweeping expansions of public ownership and economic planning. Criticism of ‘top-down’ GNDs should consider those emphasising bottom-up economic democracy. Discussions of the GND’s vague and anatopic framing should be accompanied by its function in cohering progressives around important core principles amid ecological and social crises.

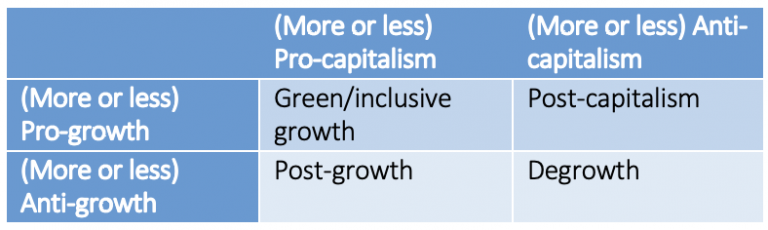

Likaj, Jacobs & Fricke present the growth debate as one between political strategies. Given the importance of capitalism in their discussion and to the competing positions, it might be better understood as a capitalism-growth debate. The authors propose ‘post-growth’ as a strategic position aiming to unify those across the debate around an abandonment of growth discourse and ambivalence towards capitalism, instead focusing on key issues.

The positions surveyed by the authors sit at the intersections of different strategic views of capitalism and growth within the debate. Despite their differences, members of each have embraced the GND as a demand and sought to make it their own.

Green or ‘inclusive growth’ sits at the intersection of pro-capitalism and pro-growth. It is associated with the most mainstream GNDs such as those proposed by the UK Labour Party and progressive US Democrats. As described, ‘post-growth’ is discursively ambivalent towards both capitalism and growth but is committed to looking beyond “incremental policy reforms” towards more transformative solutions. Ann Pettifor, who has argued for a post-growth position, has developed the GND with a focus on taking on Wall Street and transforming the financial system.

Likaj, Jacobs & Fricke present ‘degrowth’ as the intersection of anti-capitalism and anti-growth. While this position has most often been pitted against the GND, some have married the two, including Max Ajl’s A People’s Green New Deal and the proponents of a Global Green New Deal. On the other hand, ‘post-capitalism’ combines anti-capitalism and relative ambivalence towards growth. Several grassroots campaigns have operated from this tradition, arguing for an explicitly socialist GND including Labour for a Green New Deal and the Democratic Socialists of America.

Key policy differences between these interpretations include the question of ownership, with socialist conceptions supporting an expansion of publicly owned industry while others rely on stewarding private investment. Proponents of degrowth emphasise the contraction of harmful activities including animal agriculture and mineral extraction, while others emphasise investment in expanding green industry to create good green jobs. Furthermore, while some GNDs are framed as operating within the borders of one nation, others take an international scope by prioritising global justice including through climate reparations and reforms to international institutions.

These disagreements might appear to vindicate Chakrabortty characterisation of the GND as a conceptual fog. However, its diverse advocates share more than just branding. They cohere around some fundamental principles. Firstly, they recognise that previous regimes of climate politics and strategy have failed. Secondly, they all understand that climate and social injustices must be addressed in tandem. Thirdly, they share a belief in a leading role for the state in coordinating economic mobilisation and intervention in pursuit of these dual aims.

Regardless of the specifics articulated under its banner, the GND’s strength is as a compelling story that progressives can tell about the scale and nature of the crises we face, and what must be done about it. As we work through debates around capitalism and growth in the context of unprecedented and existential crises, the detail of such an economic mobilisation remains up for grabs.

The Green New Deal is therefore both a site of strategic unity and a terrain of political contestation for those who claim it across the capitalism-growth debate. This dialectic could well prove to be an animating force behind the GND’s development as progressives’ most compelling offer amid the crises of the 21st century.

Likaj, Jacobs & Fricke recognise that “’post-growth’ is not likely to become a political concept with wide popular appeal.” Conversely, the Green New Deal has already demonstrated popular purchase among activists and publics alike. If the former offers the beginnings of conceptual unity in the capitalism-growth debate, then the latter is well-placed to offer strategic unity for those engaged in practical action for political-economic transformation.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment