The pandemic provides an opportunity to choose not to return to capitalism and its failures.

Collective 20 is a group of anti-capitalist, feminist, anti-racist, environmental activists and writers from around the world who provide analysis, vision, and strategy for positive social change.

This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute

According to statistics from the World Health Organization, the number of coronavirus cases being reported worldwide remains significant. For example, in the 24 hours between July 9 and 10, over 200,000 new cases and 5,575 deaths were reported globally with the highest occurrences in the United States, Brazil and India, followed closely by large swaths of Asia, the Middle East and South America. It does not feel as though we are clear of this pandemic. If anything, the virus is very much with us and we have no vaccine or any licensed drug for its treatment.

But whether these figures warrant more caution and extended lockdown conditions, pressure is being exerted to prevent that where possible. The message in most countries—those that imposed lockdowns at any rate—has morphed from one that warned us to stay at home and save lives into one that insists we are in ‘the new normal’ and we need to get back to work.

So while scientific advisers talk of lifting measures gradually to monitor the spread of the virus, of two meters being the safe distance to avoid contracting the virus, of the virus remaining deadly and infectious, restrictions are being lifted, and quickly too, not at all in the gradual, cautious way that was promised initially. The move out of lockdown is not so much phased as frenzied.

So what changed? How did we get from being locked in our homes to ‘the new normal,’ and at such speed? Maybe the more pertinent question is why lockdown happened in the first place, allowing, as it did, the unprecedented slowing down of the capitalist machine. The most obvious answer is that the wildfire spread of coronavirus across the planet posed a danger to everybody, ruling elites included, and not just the great unwashed. But back to the original question of what changed. If the virus is still a risk, if it is still sans-vaccine, why are we being told we can emerge from our cocoons?

In part, the answer lies with our own desire to emerge. Humans are a social species and we do not only want, but need, interaction and social contact for our physical and mental well-being. “Hell is other people” but a life without other people, without love or being loved, is a greater hell. Indefinite lockdown is hardly ideal so the majority of us may want to hear it is ending, too soon or not.

However, the popular ambition to put the pandemic behind us does not explain why governments are intent on pushing ahead and easing lockdown measures. The fact is, the message has overtly shifted from being about public health to being about the economy, and protecting further damage to the economy is taking primacy over protecting human life. The factors driving decisions now are largely economic, in the modern definition of the economy as one centred on GDP and profits instead of one centred on the well-being of the population.

So, you get a situation where political leaders are trying to rationalize why social distancing is being reduced from the very safe two meters to the much less safe one meter; and why it is perfectly reasonable to reopen non-essential shops, bars and beauty salons, schools and daycares, but not to visit family and friends in their own homes. The logic is we can go shopping, eat out and in some cases go to work, but for our own good, movement between households must remain restricted. Household restrictions are explained in terms of ‘bubbles.’ People in a single household are in a bubble; they can pick one other household bubble to merge with to become a larger bubble thus allowing the people from both bubbles to visit each other indoors. Confusing? Nonsense? Why not forget about bubbles altogether and arrange to meet whoever you want when you are out at the shops or getting your haircut?

On the upside, it is a source of amusement watching the semantic gymnastics of politicians as they tell us why these are sound decisions based on the medical evidence. Undoubtedly, as confined spaces, our houses are somewhat more prone to the spread of the virus. But are we really expected to believe that a bar or a shop full of strangers with a one-meter distancing rule is any safer? The reality is, the visits we make to each other’s homes have no economic value so can remain restricted. On the other hand, opening up the retail and hospitality sectors and the means for parents to return to work have a lot of economic value. Of course, no politician can come clean about that so instead they are cartwheeling, forward rolling and hand-standing their way through press conferences.

Talking of the press and the mainstream media—those cheerleaders for the status quo who speak on our behalf and know better how we feel and think than we do ourselves—they have jumped ship when it comes to the lockdown or the threat of the virus. Their focus is all on the economy and their message is: the pandemic has destroyed state economies, national debts have reached eye-watering levels, we must crank up the economic machine and get it working again at any cost.

Not to be accused of spewing negativity, the media balances the economic misery with a little light fun, bringing us reports from the high streets: shops opening for business; hordes of happy punters desperate for some retail therapy; even happier shop assistants unable to contain their delight at being back at work—work that is probably a zero-hours’ contract on minimum wage with lousy conditions; or the hour-long queues at drive-throughs at McDonald’s. The media tells us isn’t it wonderful to see some normality, we got through the lockdown and we were in it together but we are out the other end, and surely, obviously, without a doubt, this is what we want.

The behavior of the media and the politicians is to be expected and is hardly a disappointment. What is disappointing though, and massively so, is that this global trauma has changed nothing and it is entirely assumed that in re-emerging, we are going to pick up where we left off in serving the needs of capitalism. In many ways, that is worse than the dodgy sprint out of lockdown. And although we might find that pockets of society will be forced back into lockdown to deal with spikes and further waves of the virus, the trend is to reboot the pre-COVID economy, with few, if any, countries considering alternatives to ‘normal’ or how we might do things differently.

But doing things differently is what is desperately needed. Life-before-COVID was hell for billions of us with gross income and wealth inequalities, especially in the global south; austerity, public sector cuts and the drive toward privatization; low-paid, casualized employment for many and no employment at all for many more; homelessness and housing precarity; debt, poverty and food banks. And do not forget the climate emergency, the destruction of our natural habitats and pollution of our soil, water and air. That is the world we are being told we cannot wait to get back to.

The Lockdown Was Tough but That Is Not the Entire Lockdown Story

Granted, the lockdown was tough for most people, those having to self-isolate and miss out on support from family and friends, those who lost jobs or businesses, those with chronic health problems who could not get their normal care, those with no access to outdoor space. In those respects, the end of the lockdown is good news.

But that is not the entire lockdown story. It also gave us the tiniest glimpse of another life, another way of being.

A sense of community developed in the vast majority of places and people looked out for each other—the Walking Dead it was not. We discovered the real meaning of an essential worker. Not a corporate executive or a big league football player or a celebrity or a billionaire mogul. But the doctors and nurses and carers, the engineers operating vital infrastructure, the food growers and suppliers, the delivery and postal workers, the waste collectors; these and others who put themselves at risk during the crisis to protect their communities and provide critical services. Consider the pay for the majority of these folks and then ask yourself, what kind of wacky system rewards the most important work with the lowest pay and worst working conditions, while non-essential work reaps the highest financial rewards? Somehow it seems unfair that people do not get rewarded according to the contribution their work makes to society.

And in lockdown, we consumed less. Restrictions were put in place regarding how many of each item we could buy at one time and which items became available for sale. The idea in capitalism that if you have the money and you want it, you should go ahead and buy it; you’re worth it. Conspicuous consumption had no place during the pandemic. This is in no way to suggest that authoritarian measures of rationing should be introduced but certainly, it was an example of much more modest consumption practices and it did none of us any harm.

We travelled less too. With more people working from home and generally making fewer journeys, travel by private and public transport was vastly reduced. The daily commute disappeared for many of us—is there anybody alive who was sorry about that? Restrictions were placed on public transport and global airline flights pretty much halved. The reduced travel had some happy side effects. The government-subsidized fossil fuel industry saw global oil prices and consumption both plummet. Our skies were cleaner and clearer due to a reduction in carbon emissions—the reduction was not enough on its own to trigger any reversal in global warming but it demonstrated the usefulness of reducing carbon-fueled travel.

These positives of lockdown are disappearing, unfortunately, as lockdown itself disappears. It is time to get back to reality, to fulfilling our purpose here on earth: serving capitalism. As responsible citizens, it is incumbent on us to spend and over-consume our way to economic recovery. We are leaving our homes, the roads are busy again, and the airlines are chomping at the bit for a return to pre-lockdown flights as countries begin to open their borders and resuscitate tourism.

However, this reactivation is not going to be enough for capitalism. We will be made to pay the price for slowing it down. The forecasts are unequivocal about what is coming down the pike: colossal job losses, savage public sector cuts, income tax increases for low and middle earners, wrapped up in the mother of all recessions.

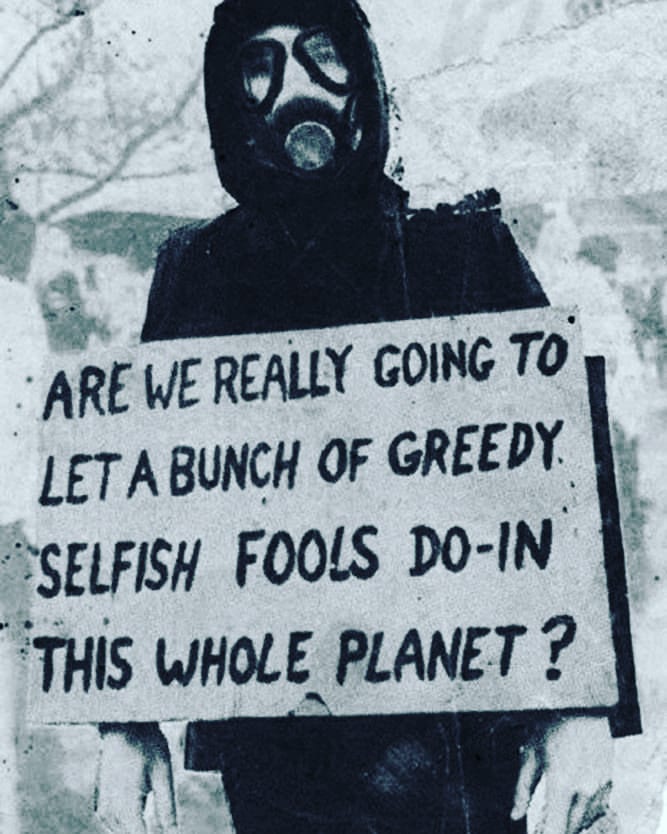

But why does it have to be like this? Why should we accept the single option of capitalism and the punishment it is going to bring on us and the planet? Are we really supposed to believe that despite millennia of ingenuity and creativity, this is the best the human race can come up with?

Capitalism favours a minority that makes up about 1 percent of the global population, and it is in the short-term interests of these elites that life-after-COVID must go back to the status quo. They will do everything in their power—their very substantial power—to make sure that happens.

The question is, are we going to let them? What if we decided to resist and instead demand another way? We have the power of numbers on our side after all—maybe the only resource we have more of. We already know what the alternatives to the status quo are. We have them waiting and ready to go. We could achieve something extraordinary if we came together and united under this common cause.

For most of the time, we are divided, black versus white, man versus woman, young versus old, gay versus straight, immigrant versus non-immigrant, working class versus professional-managerial class. Of course, these divisions are understandable and the deadly oppression that lies at their core is real. It must be opposed and destroyed. But ultimately, our biggest enemy is not each other but the 1 percent that wants to keep us subservient and subjugated. And ultimately, our distinct struggles against oppression will never reach an end as long as that minority remains in control.

If there is anything that gives the ruling elites sleepless nights, it is their fear that the masses will unite in mutual support. What if we were to do that? Not abandon our individual struggles but remain distinct while showing solidarity for each other across struggles and collaborating where we see shared goals.

And if we did, how then would we avoid these disasters of colossal job losses, savage public sector cuts and income tax increases wrapped up in the mother of all recessions?

A global recession only needs to happen if we want to keep capitalism intact and ensure the 1 percent maintains ideological control and amasses huge profits at the expense of everybody else and the planet. We are being prepared to expect this recession just so they can recover anything they might have lost, just so they can make money out of disaster.

We Have Everything We Need to Create a Different World

We could decide instead not to go back to capitalism. We could decide to reorganize the economy on the principles of prioritizing the well-being of people and of the planet; of sharing resources so that everybody has enough; of conducting production and consumption based on sane and humane need.

Beyond the straitjacket of capitalism, we have everything we need to create a different world. The means and the resources, at a global level, are readily available to provide material needs such as food, shelter, health care and education for every single person on the planet and to do so in a way that is environmentally sustainable and recognizes the true social cost of goods. People are hungry or homeless or go without adequate education and health care not because there is not enough but because the capitalist economy dictates that there be haves and have nots.

We have ample renewable energy sources to meet our global energy needs without destroying the planet. The move to renewable energy will require us to make use of a mix of sources combined with greater energy efficiency and modest, not excessive, energy consumption, but all of that is entirely achievable. Our deadly dependence on fossil fuels is not because there is no other choice but because under capitalism the fossil fuel industry has the economic and legislative power to ensure their interests come first.

The task of making the transition to a low-carbon society is enormous. It is going to require transformation from carbon-intensive industries to low-carbon counterparts. It is going to require the creation of millions of new jobs worldwide and instead of job shortages there will be an abundance of work. The new jobs will be purposeful and could be provided within the context of worker-owned co-ops that are not profit-driven and that base income on how long and hard people usefully work and on the extent of harsh conditions they must endure.

Alongside these new working environments, the not-for-profit approach would make space for other socially beneficial interventions to be introduced such as a reduced working week; increased time for volunteering, caring responsibilities, self-development and leisure and creative pursuits; affordable and secure tenure of housing with no threat of evictions; a Universal Basic Income for all with additional money for those who cannot work due to health and other reasons; and universal basic services such as health care and education. In capitalism, people are unemployed or working in precarious jobs with low pay and Dickensian conditions not because there is no work or the money is not there to give better pay or better conditions but because providing those things would divert money away from profits.

Any discussion of transitioning to a ‘green’ society invariably leads to talk of job losses as the ruling elites propagate threats about the catastrophe such transition will bring, the millions of men and women in the old industries who will be out of work. Politicians who dare to support the transition are vilified as supporting mass unemployment.

Of course, these are just straw man arguments used by the elites to protect themselves, not jobs. They do not care about jobs. If they did, they would not take production to other countries in pursuit of cheaper labour. The truth is, far from being out of work, the workers displaced from the old industries will be desperately needed in the new for their abilities and creativity, whether that means retraining or using their existing skills. Only, if we do it right, in the new industries they will be better off because they will be worker-owners availing of better working conditions, pay and universal services, and providing value to their communities and wider society.

We already have economic models that would allow us to do all of this and more. We could apply the steady-state model which would get us away from the neoliberal obsession with continuous growth and GDP as a measure of economic health. And there is participatory socialism which would allow us to produce and consume using the yardstick of living within our means, attaining equitable income for all, and giving workers truly democratic, self-managing workplaces.

But what about the monstrous deficits that countries have racked up over the pandemic months, countries that were drowning in debt long before coronavirus struck? Governments constantly tell their citizens that paying off the deficit must be the priority and that, evidently, the only way to do so is to reduce public spending by privatizing and cutting public services and increasing income tax for ordinary workers. They repeat this message so often that they have us convinced there are no other options. Such thinking takes us back to the assumption that at all costs, we must maintain economic structures as they have been, when actually nothing could be further from the truth.

For instance, one well-kept secret is that government debt is not like household debt where we get into financial trouble if we spend more than we earn. A budget deficit in itself should not be a problem, neither should government spending. The same can be said for budgets at state and regional levels. If they wish, they can have extremely high deficits without causing any economic harm, and government spending is beneficial to society, especially in times of recession.

Another largely hidden measure that governments have at their disposal is quantitative easing (QE). In very simple terms, QE is a policy whereby a central bank—or the Federal Reserve in the United States—generates new money by buying financial assets from commercial banks and financial institutions, thus increasing the money supply which in turn is supposed to stimulate the economy.

QE has been widely used across the world since the 2008 financial crisis. In the United States for example, QE programs have amounted to around $3 trillion. In Britain they sit at £375 billion. Unfortunately, instead of that money being invested in the real economy at regional and state level to boost productive businesses and industries and create jobs, it found its way into financial markets, ironically giving money to the very mechanisms that caused the crash in the first place and probably setting the scene for another crash yet to come. The UK and the United States launched further QE programs during the coronavirus pandemic, £100 billion and $700 billion respectively. History is repeating itself as once more, QE money is going to all the wrong places and is being used to bail out the usual corporate suspects and big polluters such as airlines and oil and gas companies.

QE in itself is not a bad idea. It goes wrong because the additional money is not getting to the real economy. Proposals from many quarters are calling for QE for the People or a Green QE where the money would actually reach the economy that ordinary folks live in. The potential such an injection of money would have on regional and state economies is profound. Used in conjunction with public- or community-owned banks, low- or no-interest loans could be given to local businesses and co-operatives that provide essential goods and services, all in a way that protects the environment.

Taxation is another reasonable source of revenue for governments. But why, when a government is looking to raise more revenue, is it always the income taxes of low and middle earners or the sales and value-added taxes that have to increase? At the same time, governments give tax breaks and incentives to the wealthy and turn a blind eye to their tax avoidance and evasion activities—because, it is argued, they are the wealth generators and need complete freedom to do what they do best; and also because they buy and sell what they like, including politicians.

For once though, why not make the wealthy pay? The international Tax Justice Network estimates that around $21-32 trillion of financial assets are stashed away in tax havens around the globe. By clamping down on tax havens using mechanisms such as unitary taxation, governments across the world could recoup the trillions of dollars owed to them and their citizens. Taxes could be increased too, though not for the low and middle earners this time, but for the corporations and the wealthy, to create a progressive taxation system. Of course, ending government subsidies to carbon-intensive industries such as fossil fuel, automobile and nuclear, would be imperative. Global spending on fossil fuel subsidies alone is in the region of $800 billion annually. Not loose change by any means and it could be usefully diverted to more sustainable and environmentally-sound activities.

Framing budget deficits as the problem and diverting money away from ordinary people and public services as the solutions is a carefully crafted distraction. The real dangers for governments are inflation and deflation, and these can both be controlled in a number of ways: by keeping a check on the financial economy; by investing in the real and green economy; by ensuring a sustainable tax base; and ultimately by managing how much money goes into circulation.

Use This Crisis to Define a New Economy

The thing is, as we move out of lockdown and into a post-COVID world, there will be a recovery. If we slip right back into capitalism, that recovery will mean the creation of money for investment in financial markets so that the wealthy can stay wealthy. The new QE programs are proof that this is already happening. Simultaneously, the rest of us will be forced to endure more decades of austerity and recession, all the while being pushed toward the cliff edge of the climate crisis. We can decide to accept that or we can decide to turn all of it on its head by demanding that the created money is redirected into the alternatives for a greener, kinder world?

None of the progressive ideas presented above are far-fetched pie-in-the-sky. They are backed with robust evidence. More than can be counted are already in place, albeit on a small scale, and countless others have the support of tens of thousands of us through popular campaigns. Left activists are hard at work all over the world whether it be organizing action on climate change or anti-neoliberal uprisings; promoting sustainable farming and food growing practices; defying racism, sexism and homophobia; protecting natural habitats and endangered species; supporting the homeless and constructing co-operative housing projects; establishing community-owned renewable energy projects, community-owned banks and worker-owned co-operatives; implementing experiments in participatory budgeting; or building networks of solidarity and collaboration.

The pandemic, for all its tragedy, has offered the Left a moment. What we decide to do now is all-important.

We can simply let life return to ‘normal,’ face the misery and suffering of the anticipated economic depression, and allow the ruling elites and their political servants to define the economy.

Or we can use this crisis to define a new economy that showcases alternatives and proves they’re not only possible but necessary.

The choice can be ours. So, which will it be?

Be the first to comment