Online gig workers in the global south receive lower pay and less work due to discrimination from clients largely based in the global north, with no legal recourse, a new study of Cloudwork platforms has found.

The Gig Economy Project, led by Ben Wray, was initiated by BRAVE NEW EUROPE enabling us to provide analysis, updates, ideas, and reports from all across Europe on the Gig Economy.

This series of articles concerning the Gig Economy in the EU was made possible thanks to the generous support of the Foundation Menschenwürde und Arbeitswelt

Cloudworkers in the global south face consistent discrimination when working for clients on digital labour platforms, who are largely located in the global north, a new report has found.

The University of Oxford’s Fair Work foundation today [15 June] published ’Work in the planetary labour market: Fair Work Cloud Ratings 2021’, which examines 17 digital labour platforms which match cloud workers – those whose work is performed entirely online – from around the world with clients looking for tasks to be completed. A wide range of work is now conducted on this online gig work basis, from translation services to graphics design.

The cloudwork gig economy has grown enormously in recent years, a process which has been accelerated by the pandemic which has induced a rise in remote working and job precarity. Freelancerdotcom, one of the largest Cloudwork platforms, has 31 million registered workers, equivalent to the population of Peru.

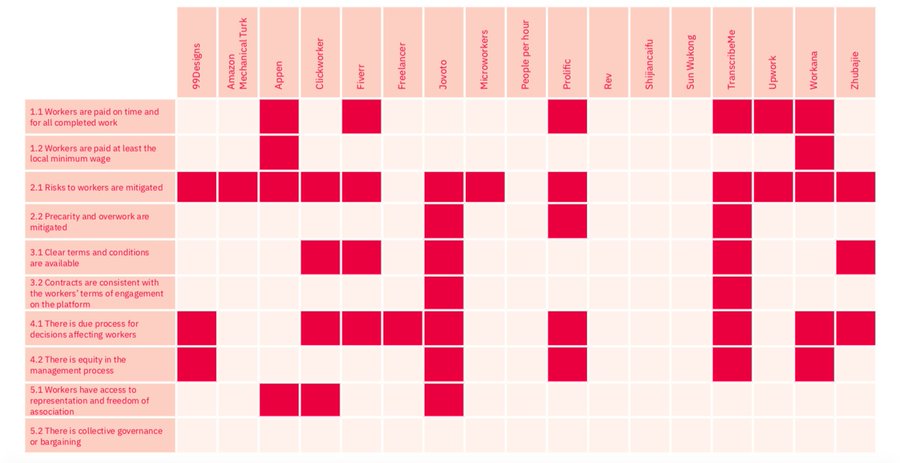

The report finds that the majority of platforms fell short on most of Fair Work’s indicators, with just five out of 17 platforms able to evidence that workers were always paid within an agreed timeframe and for all completed work, while just two guaranteed that workers would be paid at least the local minimum wage. Just three platforms could evidence that workers had the right to fair representation and that freedom of association was not inhibited, while none could provide evidence of collective bargaining agreements.

Other systemic problems include platforms unilaterally changing terms of service whenever they like; a complete lack of transparency in management processes, which often include automated penalties and sanctions with no recourse to appeal; and an almost complete lack of government regulation, as Cloudwork platforms “evade regulatory oversight in most of the countries they operate in.”

“This gap in regulation and enforcement has allowed platforms to take advantage of and exploit worker vulnerabilities,” the report adds.

Freelancerdotcom and Amazon Mechanical Turk (Amazon’s micro-tasking Cloudwork platform) received ratings of just one out of ten. Just two platforms, Jovoto and TranscribeMe, received ratings above five out of ten.

Speaking at the launch of the report, Dr Hannah Johnston, a co-author of the report from Northeastern University, said that Cloudworkers in the global south get a particularly rough deal.

“We asked workers about their experience of discrimination, and geographic discrimination emerged as one of the most common challenges that workers face,” Johnston said. “For example many workers described situations where clients did not want to work with them, or wanted to pay them less because of where they lived.”

She added: “From workers in our survey we heard countless examples of geographic discrimination which was completely unrelated to the task. Geographic discrimination was more common from low-income countries, in regions like Africa, Latin America and parts of Asia.”

Dr Uma Rani, Senior Economist at the International Labour Organisation, also spoke at the launch event, and said that the findings “resonated with the ILO’s work on discrimination of workers from the global south.”

The report found that workers reported suspicions that “buyers pay less to Asians and more to Europeans” for comparable work, while other posts by clients for jobs have stated they will “only work with sellers in the US and UK” or “that workers from selected countries like Kenya, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, or Venezuela need not apply”.

“Other workers have been explicitly told that their labour is worth less because they live in low-income countries,” the report states, adding that there is no “legal recourse in the face of discrimination” due to the “transjurisdictional nature of cloudwork”.

The study identified cases where cloudworkers in the global south have responded to discrimination by seeking to mask their IP locations or create accounts “so as to appear from wealthier regions”.

“When talking with workers about why they would misrepresent themselves on their profiles, workers were quick to confirm that they can more easily secure work if they appear to be from higher-income countries, or if they adopt a different, frequently white, profile picture,” the report adds.

There were positives from the report, including that six platforms responded to Fair Work’s engagement with them by making improvements, including ‘TranscribeMe’ which added an anti-discrimination policy into their Terms of Service and ‘Workana’ which “added public policy stating that jobs will be removed from the platform if they pay below the minimum wage in the workers’ local jurisdiction.”

Dr Kelle Howson, co-author of the report from the University of Oxford, said: “A lot of the platforms we engaged with found the Fairwork principles to be a useful resource, which led the six platforms to make changes.”

The report found that cloudworkers lacked “structural power” due to the dispersed nature of the workforce, the control exercised by platforms and the “power asymmetry” between workers and clients which are built into platform algorithms, including through the customer evaluation and performance metrics processes.

Nonetheless, there are examples of cloud workers co-ordinating with one another, most famously through the ‘Turkopticon’ app which allows workers to share information on clients using Amazon Mechanical Turk, creating a blacklist of employers who do not pay for completed work, for example.

Melissa (name changed), who lives in Sao Paolo, Brazil and works on Amazon Mechanical Turk, told the Fair Work report that: “We have a really strong community. Every time there’s a scammer, the first thing we do is go to the forum and tell people.

“The community is very important; I couldn’t do this job without them. We have web extensions which help us avoid scams and get the best jobs. These are really helpful and were all made by the community.”

Fairwork has launched a “Fairwork pledge”, where companies and organisations which abide by FairWork’s five principles can be recognised as a Fairwork employer.

Professor Mark Graham, director of the Fairwork Foundation, said: “As part of our vision for a fairer future of work, we’re setting out a pathway to realise that ambition and one of the ways we’re doing that, in addition to calling for tougher regulation, is through the launch of the Fairwork Pledge. We urge others to sign up to the pledge today and help our vision of fair work become a reality for all platform workers.”

Be the first to comment