A study by the Fair Work Foundation which rates platform giants against a check-list of fair work standards has found that Ola, Bolt and Amazon Flex met none of the fair work requirements, achieving a score of zero.

The Gig Economy Project, led by Ben Wray, was initiated by BRAVE NEW EUROPE enabling us to provide analysis, updates, ideas, and reports from all across Europe on the Gig Economy.

This series of articles concerning the Gig Economy in the EU was made possible thanks to the generous support of the Foundation Menschenwürde und Arbeitswelt

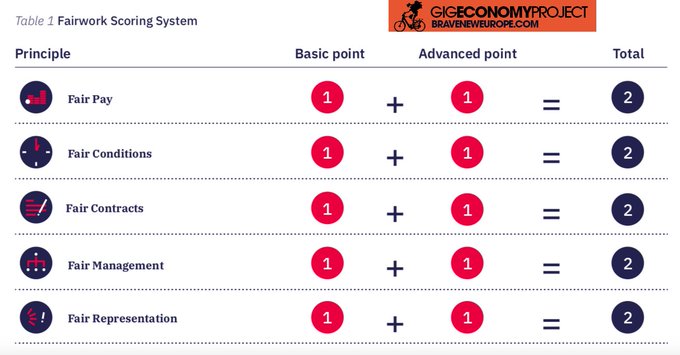

In the first ever UK Fair Work rating, 11 of the largest platform companies were assessed based on fair pay, fair conditions, fair contracts, fair management and fair representation. Just two of the platforms, Just Eat and Pedal Me, achieved a score above 50 per cent, while Deliveroo was rated five out of 10, TaskRabbit, Uber Eats and Uber two out of 10, Helpling and Stuart one out of 10 and 0 for Ola, Bolt and Amazon Flex.

Only two platforms, Pedal Me and Just Eat, could guarantee that their workers would take home earnings equal to or above the minimum wage, while just one platform, Pedal Me, assures workers freedom of association and the right to a collective voice.

“The 2021 UK Fairwork scores presented in this report suggest that much remains to be done to ensure minimum standards of fairness for UK-based platform workers,” the report states. “Within a rapidly growing platform economy and evolving regulatory context, we hope this report will draw attention to persistent gaps in worker protections and the need for stronger labour standards in the UK’s platform economy.”

The report also highlights four key themes of the gig economy in the UK:

1) That gig workers in the UK “tend to be from migrant or ethnic minority backgrounds”;

2) That gig work is part of a deepening fragmentation of work through “low-road” management strategies, including subcontracting and the misuse of the self-employed classification;

3) That there is a legal counterbalancing to the power of platforms over gig workers, highlighted by the UK Supreme Court ruling against Uber in February;

4) The pervasiveness of unpaid labour-time in the gig economy, including waiting time, training time and travel time. The outsourcing of costs from the platform to the worker means that, when all the costs are added up, a large section of gig workers are not making the minimum wage.

Speaking at the launch of the report at an online event on Tuesday [25 May] afternoon, Dr Matthew Cole, one of the authors of the study from the Fairwork Foundation at the University of Oxford, said that the low scores were “the outcome of the free market largely left to itself”.

“Few companies are choosing their outcomes for the workers, most won’t do so unless they are forced by regulation and worker organisation,” he added.

Commenting, Dalia Gebrial, PhD researcher at LSE and Research Associate at work think-tank Autonomy UK, said that the report’s findings on the prevalence of ethnic minority and migrant labour showed how “the racialisation of platform work” is “not a bug, it’s the feature”.

“Race and migration are central analytic categories for understanding what platform work is doing and how it is doing it,” she added.

Gebrial explained that platform work has been successful in industries and sectors where precarity was historically the norm, like in home care.

“The social and political contexts of these workforces lend themselves to being a site of experimentation for this model of exploitation,” she said, adding: “Capitalism tends to sharpen its tools on the bodies of the most marginalised”.

Gebrial highlighted the fact that not only do platforms outsource risk to the workers in the sense of the costs of production like the car and insurance, but workers are also “treated as risks in themselves, in a way that is very connected to how they are racialised”. For instance if there is a conflict where it is the customer’s word versus the worker’s, the platform always sides with the customer, usually meaning the worker is disconnected from the app. These punitive forms of management towards workers, where they are treated as inherently “risky to the community”, is connected to older forms of racialisation of work.

Frances O’Grady, General Secretary of the British Trades Union Congress (TUC), agreed with Gebrial, stating that minority ethnic and migrant gig workers are being treated as “a lab for being watched, tracked and atomised in a way that is designed to spread throughout the workforce”.

O’Grady said that she believed platform companies were “rattled” by the Uber Supreme Court judgement, especially by the judge’s finding that workers should be paid from the moment they log-in and therefore “no more working for free”.

The TUC leader added that they are pushing for a new post-Brexit employment framework in the UK which included that all workers, regardless of employment status, should have the same basic rights, such as minimum wage, sick pay, holiday pay, health & safety rights and the right to collectively organise.

O’Grady also said that the burden of proof of an employment status other than worker should be on the employer not the employee, and that when an individual worker wins in an employment tribunal, it should set the legal precedent for all workers, not just for that individual case.

Emiliano Mellino, Community Organiser at the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which recently exposed in an investigation that 41% of Deliveroo riders were earning below the minimum wage, told the meeting that he disagreed with Fair Work’s positive rating of Deliveroo in terms of ‘fair management’ – that they “provide a fair system of due process for decisions affecting workers” and “equity in the management process”, according to the report.

Mellino said that from what he has heard from Deliveroo riders “there is no fair management”, because “when they are terminated they are told very generally the reason why they were terminated, but they are not given any of the details” because the platform’s algorithm operates as a “black box”.

He added: “How can we have a due process when none of the details of the alleged infraction are being told [to the worker in question]?”

Mellino argued that there was wider reasons beyond the platform economy which are also essential to explaining low-pay in the UK. He cited a 2019 study commissioned by the UK Government which found that the extent of wage theft in the UK was £3.1 billion per annum. The study also found that the average company can expect to get a minimum wage inspection once every 500 years, meaning there was “virtually no enforcement of minimum wage legislation”.

Alex Marshall, President of the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain (IWGB), added: “Workers are being dismissed from their jobs, sometimes with just days’ warning. The reasons the companies give are generally vague and nonspecific, and often appear to be automated, having no basis in reality. Couriers and private hire drivers are denied the right to have their case heard, or to appeal, even if they have done nothing wrong.”

To read the report, ’Fair Work UK Ratings 2021: Labour Standards in the gig economy’, click here.

Be the first to comment