Six political prisoners who targeted factories arming Israel’s genocide are weeks into a hunger strike. But in contrast to the IRA’s 1980s hunger strike, this one is being blanked by the media

Jonathan Cook is the author of three books on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and a winner of the Martha Gellhorn Special Prize for Journalism. His website and blog can be found at www.jonathan-cook.net

Cross-posted from Jonathan’s Substack

If we truly had a free media in the UK, rather than one serving the interests only of the state and billionaire class, this would be a front-page news story:

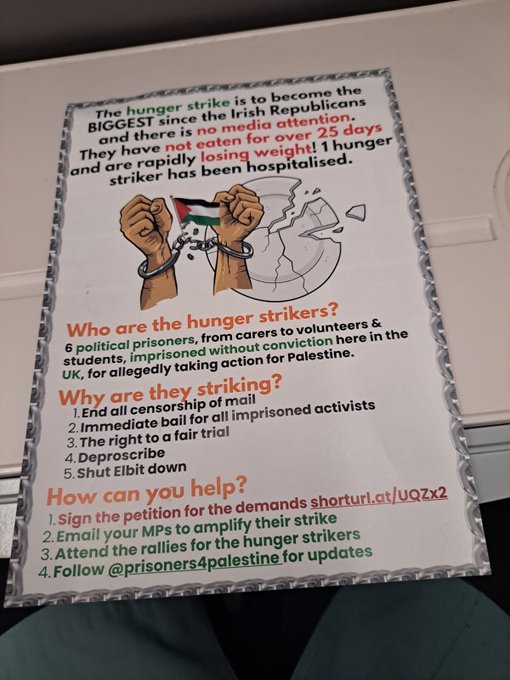

Six political prisoners – held unlawfully for a year or more on remand, and retroactively deemed to be “terrorists” for trying to stop the Gaza genocide – have been on hunger strike for many weeks in prison. At least one is already seriously ill.

There has been blanket silence from the media on these developments, and barely any coverage of the appalling conditions these political prisoners are being subjected to since Palestine Action was reclassified by Sir Keir Starmer’s government as a terrorist organisation – after their arrests.

Notably, it is the first time a direct-action group, one that directs its violence against property – that is, factories making weapons to kill civilians in Gaza – rather than people, has been declared a terrorist organisation and put on the same footing as al-Qaeda and Islamic State.

Under Britain’s draconian Terrorism Act, anyone expressing an opinion, even inadvertently, that might “encourage support” for a proscribed organisation – now including Palestine Action – can be arrested for supporting terrorism and faces a terrorism conviction.

With at least 2,500 people arrested for holding placards stating “I oppose genocide. I support Palestine Action”, Britain’s jails could soon be flooded with many more such political prisoners.

A judicial review of the government’s decision was heard in the past few days at the High Court, though again you are unlikely to know this, given the lack of interest from the British media. The judges’ ruling on the lawfulness of the government’s decision is expected in mid-January.

But a related ruling this week from a judge in Jersey, hearing a terrorism case against peace activist Natalie Strecker, opens the door even more widely to political prosecutions. Despite freeing Strecker, Judge Saunders appeared to accept the British government’s argument that it is unlawful to advocate for international law, which expressly states that occupied peoples such as the Palestinians have a right to resist their illegal occupation.

For anyone with a long memory, the current silence from our media should be shocking. The last major hunger strike by political prisoners in the UK occurred in the early 1980s. It was then that the Provisional IRA – an organisation that expressly claimed responsibility for bombing pubs, hotels, and public parks, in acts that killed many hundreds of civilians – organised a hunger strike in the Maze Prison, near Belfast, demanding improved prison conditions.

One of the hunger strikers, Bobby Sands, became a household name in Britain. His story dominated headlines for weeks, and led to a major confrontation, through the media, with the Thatcher government. His death reverberated long afterwards, and ultimately ushered in the Northern Ireland peace process.

Contrast that with our current moment. Imprisoned members of Palestine Action, an organisation that expressly eschews violence against people, and which is trying to stop a slaughter in Gaza that major human groups and genocide scholars are agreed amounts to a genocide, are on hunger strike because their rights are being grossly and systematically violated – as political prisoners. And there’s barely a peep from the media.

Notably, there was similarly minimal media coverage of the prison conditions and legal abuses of another recent political prisoner. Journalist and publisher Julian Assange spent five years in London’s high-security Belmarsh prison, on trumped-up charges to justify extradition to the US for publishing details of British and US war crimes in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The media gave his case the most cursory coverage and avoided detailing what he was accused of – because those details would have painted a damning picture the British and US governments. Without a trace of irony, the press paid more attention to speeches from the very politicians jailing Assange in which they condemned the suffering of political prisoners, including journalists, in Russia and China.

None of this should be normal. The Palestine Action hunger strike is very obviously a major news story. The fact that it is getting almost no coverage is evidence of active government suppression, and active media collusion in that suppression.

Even hunger strikes by Palestinian political prisoners held illegally in Israeli jails receive more coverage from the Israeli press than the British media are giving a hunger strike by the political prisoners of Palestine Action.

Francesca Nadin, a former Palestine Action political prisoner, has told the Electronic Intifada that “mainstream” journalists who show interest in the hunger strike cannot get their stories past editors. She observes that there has been “almost a complete blackout in the mainstream media about this story”.

Editors, it seems, are often using legal concerns as cover for refusing to report the strike. This is a pretext, not a reason.

Britain has a voluntary system of military censorship, called the D-Notice Committee. By joining the committee, British editors effectively agree to avoid reporting on anything the government declares to be a “national security” matter. In practice, that often concerns issues that might embarrass the government.

For editors, the system offers plausible deniability as they collude in censorship. For readers, it makes the media more than useless on the most urgent and serious matters of our time.

In contrast to the 1980s, when the British media was reporting – even if rarely sympathetically – IRA hunger strikes, the media is now even more under the thumb of the British state. As evidence, note the Guardian’s U-turn on the D-Notice Committee in 2014, when it faced harsh pushback from the security services over its Edward Snowden revelations into illegal mass surveillance by western states of their own populations.

For the first time the paper agreed to join the D-Notice Committee, becoming fully absorbed into the architecture of the national security state. It was rewarded with front-page “exclusive” interviews with the heads of MI5 and MI6. The Guardian revelled in what should have been the ultimate mark of shame for a newspaper that claimed to be a watchdog on power.

The truth is the assault on basic freedoms in Britain is now well advanced. Political dissent is under siege. The hunger strikes are not being televised, nor will the last gasps of our dying freedom.

All my posts are freely accessible, but my journalism is possible only because of the support of readers. If you liked this article or any of the others, please consider sharing it with friends and making a donation to support my work. You can do so by becoming a paid Substack subscriber, or donate via Paypal or my bank account, or alternatively set up a monthly direct debit mandate with GoCardless. A complete archive of my writings is available on my website. I’m on Twitter and Facebook.

Be the first to comment