Despite all the euphoric reports by the EU about a Greek economic recovery, it has always been clear that the Greek crisis will never go away and each time it returns, it will be worse.

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts Blog

On Thursday night, EU leaders again failed to agree on how to provide proper fiscal support for hard-hit member states to cope with the health costs of the coronavirus pandemic and collapse of their economies from the lockdowns.

The EU leaders have already agreed to a €540bn package of emergency measures. This sounds a lot but is really just a bunch of loans from the European Stability Mechanism, which lends only on strict conditions on spending and repayment by member states who borrow. Only E38bn has been offered without conditions for health system support across the whole Eurozone. The so-called coronavirus mutual bond where the debt is shared by all is a dead duck.

At Thursday’s meeting the countries hardest hit, backed by France, demanded a massive direct fiscal boost. But the ‘frugal four’ of Germany, Austria, Netherlands and Finland again rejected straight grants in any proposed ‘recovery fund’. While the EU Commission President von der Leyen talked about a E1trn fund, this would be mostly just more loans. Guy Verhofstadt, a former Belgian prime minister, said piling more loans on embattled countries risked causing a “new sovereign debt crisis”. “Grants are like water in a fire fight while loans are the fuel,” he said.

Lucas Guttenberg of the Jacques Delors Centre said there was a temptation for the EU to come up with huge headline figures for the fund, but this needed to be backed with significant transfers of cash to the worst affected countries, not just guarantees for private investment projects and loans that added to their debts. “The question is do we want to create an instrument that gives Italy and Spain significantly more fiscal space?” he said. “That requires a lot more real money on the table.”

But Germany’s Merkel insisted that any funding borrowed on the markets must ultimately be paid back. There were “limits” on what kind of aid could be offered, she told leaders, adding that grants “do not belong in the category of what I can agree”. So the recovery plan looks like offering just more loans plus guarantees in return for increased investment by private sector companies. But “we are at a moment where companies are not going to invest because there is a lot of uncertainty,” said Grégory Claeys, a research fellow at Bruegel, the think-tank. What economies needed was direct public spending, he added, because the private sector will do little.

The EU Commission is going to fund its plan by doubling the EU annual budget from 1% of EU GDP to 2% along with some borrowing in capital markets. But as I argued in a previous post, this will be far too little to turn Europe’s weaker economies around once the lockdowns are over. What Europe needs is an outright public investment programme, budgeted at around 20% of EU GDP. This should by-pass the banks and launch directly employed public projects in health, education, renewable energy and technology across borders in Europe. But there is no chance of that.

While the EU Commission ponders what to do and reports back next month, Europe as a whole, and the weaker economies of the south in particular, are spiralling into a slump that will exceed the depths of the Great Recession in 2008-9. Much has been talked about the impact on relatively large economies like Italy and Spain. But there is less talk about the country that was crushed by the Great Recession, the euro debt crisis and the actions of the Troika (the EU, ECB and IMF) – Greece.

I followed the Greek drama in a dozen posts on this blog since 2012 (search for ‘Greece’). Now the tragedy of the Greece has become a drama of three acts. The first was the global financial crash and ensuing slump that exposed the faultlines in the so-called boom of the early years of Greece’s membership of the Eurozone. The second was the terrible period of austerity imposed by the Troika to which the left Syriza government eventually capitulated, despite the referendum vote of the Greek people to reject the Troika’s draconian measures.

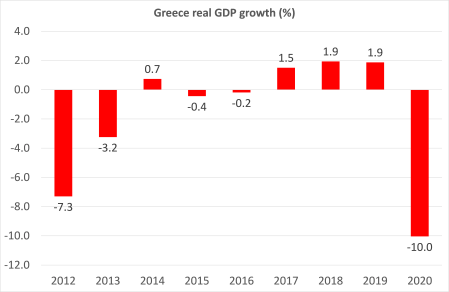

Since then, the Greek capitalist economy has struggled to recover. By 2017, the deep depression ended and there was some limited growth. But the real GDP level is still some 25% below its 2010 level. And real GDP growth started to slow again (as it did in many countries) just before the pandemic hit. Productive investment has been flat for seven years, while employment is down by one-third because so many educated Greeks (half a million) have emigrated to find work. Large parts of the capitalist sector are in a zombie state – over one-third of loans made by Greek banks are not being serviced and Greek banks have the highest level of non-performing loans in Europe

Above all, Greek capital has experienced low and falling profitability. According to the Penn World Tables, the internal rate of return fell 23% from 1997 to 2012. From then to 2017, it recovered by just 14%. But in 2017, profitability was still 12% below 1997. Since 2017, according to AMECO data, profitability improved, but was still 10% below the pre-crisis level of 2007.

But now Greece’s tragedy is in its third act with the pandemic. The global economy has entered a slump in production, trade investment and employment that will outstrip the Great Recession of 2008-9, previously the deepest slump since the 1930s. And Greece is right in the firing line. Around 25% of its economy is in tourism and that is being decimated.

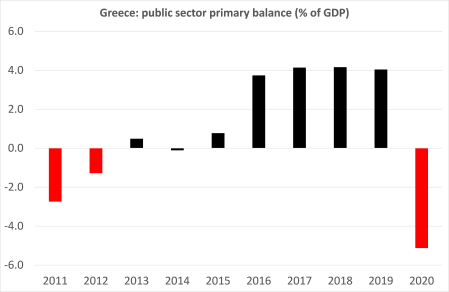

And the government is no financial position to spend to save industry, jobs and incomes. For years, under the imposition of the Troika first, and later the EU, Greek governments have been forced to run large primary surpluses on their budgets – in other words the government must tax people much more than any spending on public services.

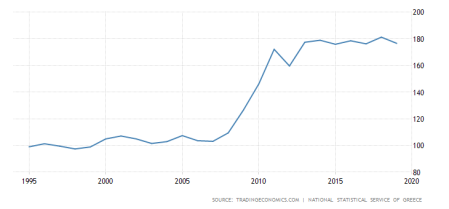

The difference has been used to pay the rising burden of interest on the astronomical level of public debt. Every year, 3.6% of GDP is paid in interest on public debt that continued to mount to 180% of GDP.

Now the slump will drive down real GDP by 10% according to the IMF and send the debt level to 200% of GDP. This year, the gross financing needs of the government will reach 25% of GDP (that’s the budget deficit and maturing debt repayments). Unless fiscal support comes from the rest of the EU, the Greek people will be plunged into another long round of austerity once the lockdown is over.

And there is little sign that Greece will get any more help than it did in Act Two – except to absorb yet more debt.

The failure of the EU leaders to give fiscal support produced a frustrated reaction from former Syriza finance minister and ‘rockstar’ economist Yanis Varoufakis. Now recently elected as an MP, Varoufakis took note of the EU leaders’ reaction to plight of Italy and Greece. He thought that “the disintegration of the eurozone has begun. Austerity will be worse than in 2011″. As he argued back in 2015 during Greek debt crisis, the northern states ought to see “common sense” as it was in their interest to help the likes of Italy and Greece to save the euro. But if they will not,then Varoufakis reckoned that “the euro was a failed project” and all his work to save Greece and keep it in the euro had been wasted.

Back in 2015, Varoufakis, the self-styled ‘erratic Marxist’, as Syriza’s finance minister, had tried to persuade the Euro leaders of the need for unity. He had argued that the long depression of the last ten years was “not an environment for radical socialist policies after all”. Instead “it is the Left’s historical duty, at this particular juncture, to stabilise capitalism; to save European capitalism from itself and from the inane handlers of the Eurozone’s inevitable crisis”. He said “we are just not ready to plug the chasm that a collapsing European capitalism will open up with a functioning socialist system”. So his solution at the time was that he should “work towards a broad coalition, even with right-wingers, the purpose of which ought to be the resolution of the Eurozone crisis and the stabilisation of the European Union… Ironically, those of us who loathe the Eurozone have a moral obligation to save it!”

In 2015, the role of Tsipras and the Syriza was even worse. I’m singling out Varoufakis because he claims allegiance to Marxism, of a sort, and opposition to the capitulation by Syriza in Act Two. But in his memoirs covering the period of his negotiations with the EU ‘right-wingers’ called Adults in the Room, Varoufakis shows that he went all the way and back to get a deal from the Troika that would not throw Greece into permanent penury – but failed.

In a new book, Capitulation between Adults, Eric Toussaint, scathingly exposes the wrongheaded approach of the ‘erratic marxist’. Toussaint, who at the time acted as a consultant on debt for the Greek parliament, argues that there was an alternative policy that Syriza and Varoufakis could have adopted.

In a recent interview, Varoufakis was asked “what would I have done differently with the information I had at the time? I think I should have been far less conciliatory to the troika. I should have been far tougher. I should not have sought an interim agreement. I should have given them an ultimatum: “a restructure of debt, or we are out of the euro today”.

Too late for that change of view now. Instead Act Three of the tragedy has begun.

Be the first to comment