![]()

Orlando Barria/EPA

Peter McPhee, University of Melbourne

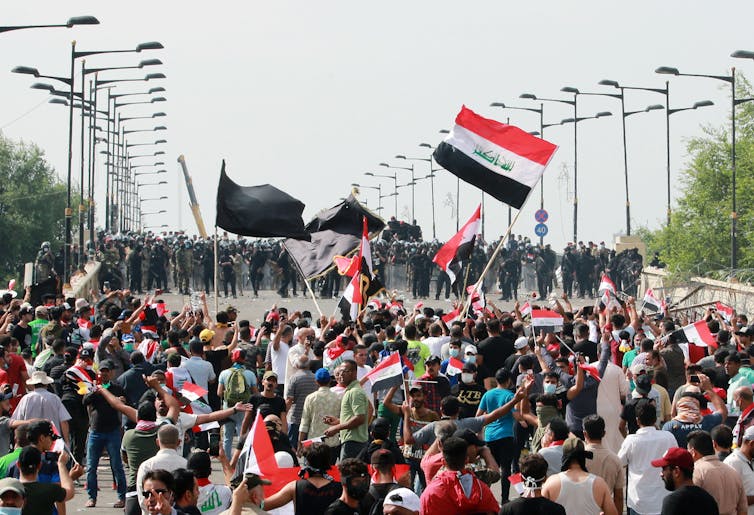

We live in a world of violent challenges to the status quo, from Chile and Iraq to Hong Kong, Catalonia and the Extinction Rebellion. These protests are usually presented in the media simply as expressions of rage at “the system” and are eminently suitable for TV news coverage, where they flash across our screens in 15-second splashes of colour, smoke and sometimes blood.

These are huge rebellions. In Chile, for example, an estimated one million people demonstrated last month. By the next day, 19 people had died, nearly 2,500 had been injured and more than 2,800 arrested.

How might we make sense of these upheavals? Are they revolutionary or just a series of spectacular eruptions of anger? And are they doomed to fail?

Ahmed Jalil/EPA

Key characteristics of a revolution

As an historian of the French Revolution of 1789-99, I often ponder the similarities between the five great revolutions of the modern world – the English Revolution (1649), American Revolution (1776), French Revolution (1789), Russian Revolution (1917) and Chinese Revolution (1949).

A key question today is whether the rebellions we are currently witnessing are also revolutionary.

A model of revolution drawn from the five great revolutions can tell us much about why they occur and take particular trajectories. The key characteristics are:

- long-term causes and the popularity of a socio-political ideology at odds with the regime in power

- short-term triggers of widespread protest

- moments of violent confrontation the power-holders are unable to contain as sections of the armed forces defect to rebels

- the consolidation of a broad and victorious alliance against the existing regime

- a subsequent fracturing of the revolutionary alliance as competing factions vie for power

- the re-establishment of a new order when a revolutionary leader succeeds in consolidating power.

Fazry Ismail/EPA

Why today’s protests are not revolutionary

This model indicates the upheavals in our contemporary world are not revolutionary – or not yet.

The most likely to become revolutionary is in Iraq, where the regime has shown a willingness to kill its own citizens (more than 300 in October alone). This indicates that any concessions to demonstrators will inevitably be regarded as inadequate.

We do not know how the extraordinary rebellion in Hong Kong will end, but it may be very telling there does not seem to have been significant defection from the police or army to the protest movement.

People grow angry far more often than they rebel. And rebellions rarely become revolutions.

So, we need to distinguish between major revolutions that transform social and political structures, coups by armed elites and common forms of protest over particular issues. An example of this is the massive, violent and ultimately successful protests in Ecuador last month that forced the government to cancel an austerity package.

Paolo Aguilar/EPA

The protests in Hong Kong and Catalonia fall into yet another category: they have limited aims for political sovereignty rather than more general objectives.

All successful revolutions are characterised by broad alliances at the outset as the deep-seated grievances of a range of social groups coalesce around opposition to the existing regime.

They begin with mass support. For that reason, the Extinction Rebellion will likely only succeed with modest goals of pushing reluctant governments to do more about climate change, rather than its far more ambitious aspirations of a national Citizen Assembly, populated by ordinary people chosen atrandom, to come up with a programme for change.

Mass protests also fail when they are unable to create unity around core objectives. The Arab Spring, for instance, held so much promise after blossoming in 2010, but with the possible exception of Tunisia, failed to lead to meaningful change.

Revolutionary alliances collapsed rapidly into civil war (as in Libya) or failed to neutralise the armed forces (as in Egypt and Syria).

Why is there so much anger?

Fundamental to an understanding of the rage so evident today is the “democratic deficit”. This refers to public anger at the way the high-water mark of democratic reform around the globe in the 1990s – accompanied by the siren song of economic globalisation – has had such uneven social outcomes.

One expression of this anger has been the rise of fearful xenophobia expertly captured by populist politicians, most famously in the case of Donald Trump, but including many others from Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil to Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Victor Orbán in Hungary.

Indeed, there are some who claim that western liberalism has now failed).

Elsewhere, the anger is popular rather than populist. In upheavals from Lebanon and Iraq to Zimbabwe and Chile, resentment is particularly focused on the evidence of widespread corruption as elites flout the basic norms of transparency and equity in siphoning government money into their pockets and those of their cronies.

Wael Hamzeh/EPA

The broader context of today’s upheavals also includes the uneven withdrawal of the US from international engagement, providing new opportunities for two authoritarian superpowers (Russia and China) driven by dreams of new empires.

The United Nations, meanwhile, is floundering in its attempt to provide alternative leadership through a rules-based international system.

The state of the world economy also plays a role. In places where economic growth is stagnant, minor price increases are more than just irritants. They explode into rebellions, such as the recent tax on WhatsApp in Lebanon and the metro fare rise in Chile.

There was already deep-seated anger in both places. Chile, for example, is one of Latin America’s wealthiest countries, but has one of the worst levels of income equality among the 36 nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Rebellions with new characteristics

Of course, we do not know how these protest movements will end. While it is unlikely any of the rebellions will result in revolutionary change, we are witnessing distinctly 21st century upheavals with new characteristics.

One of the most influential approaches to understanding the long-term history and nature of protest and insurrection has come from the American sociologist Charles Tilly.

Tilly’s studies of European history have identified two key characteristics.

First, forms of protest change across time as a function of wider changes in economic and political structures. The food riots of pre-industrial society, for instance, gave way to the strikes and political demonstrations of the modern world.

And today, the transnational reach of Extinction Rebellion is symptomatic of a new global age. There are also new protest tactics emerging, such as the flashmobs and Lennon walls in Hong Kong.

Bianca de Marchi/AAP

Tilly’s second theory was that collective protest, both peaceful and violent, is endemic rather than confined to years of spectacular revolutionary upheaval, such as 1789 or 1917. It is a continuing expression of conflict between “contenders” for power, including the state. It is part of the historical fabric of all societies.

Even in a stable and prosperous country like Australia in 2019, there is a deep cynicism around a commitment to the common good. This has been created by a lack of clear leadership on climate change and energy policy, self-serving corporate governance and fortress politics.

All this suggests that Prime Minister Scott Morrison is not only whistling in the wind if he thinks that he can dictate the nature of and even reduce protest in contemporary Australia – he is also ignorant of its history.

Peter McPhee, Emeritus professor, University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Be the first to comment