How markets get corrupted, and nobody seems to want to clean them up

Counterbalance is a newsletter from a new anti-monopoly organisation, the Balanced Economy Project

Cross-posted from Counterbalance

To subscribe to The Counterbalance click Here

Richard Allen may have had his career direction set for him in 1973 at the age of ten, when his uncle gave him the Beatles album Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and a record called Keynsham by the appealingly ludicrous British “national treasure,” the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band1. He began collecting obscure records and in the 1980s started writing for music fanzines including the Encyclopaedia Psychedelica and Freakbeat: the latter sometimes came with 3D glasses and was so garish that some readers complained they couldn’t read it.

In 1994, tired of complaints that readers couldn’t find the obscure records he was writing about, he set up Freak Emporium, an online mail-order business modelled on Richard Branson’s Virgin Mail Order. It grew fast and soon had its own warehouse, offices, and 10 staff. A bit like the obsessive record shop owner played by John Cusack in the movie High Fidelity, he competed on quirky quality as well as on price. “People would buy stuff from us that they had never heard of before just because they knew we had good taste,” Allen said. “I guess it was a bit like selling fine wine: ‘try this: you may like it!’ ” He set up his own record label, Delerium, and discovered, among others, the band Porcupine Tree, which began as a joke but went on to global success, with Allen as its manager and press agent.

Violent competition

In the early 2000s he noticed new online competitors violently undercutting his business. At a trade fair in London he found out what was going on: new entrants were physically shipping goods out in bulk to the tax havens of Jersey and Guernsey, then shipping them back in smaller parcels, each with a low enough value to qualify for an exemption called Low Value Consignment Relief, or LVCR, which allowed them to escape Value Added Tax. (VAT is a consumption-based tax, then charged at 17.5 percent, and it’s a big deal, making up nearly a fifth of all UK government tax revenues.)

That 17.5 percent advantage, Allen knew, was life and death for Freak Emporium. So, posing as a prospective participant, he asked how it worked. They told him he’d have to set up an offshore company in the tax haven and behave oddly: the company had to be nominally controlled by nominee directors, and Allen had to be a shareholder but if he wanted to give instructions it could only be by phone and off the record.

“I realised then that this was dodgy,” he said. “They said ‘if you don’t join in, you will go out of business,’ like a threat. It felt like a protection racket.”

Allen – who was not angling for higher or lower tax rates, just a level playing field – took the fateful decision to fight it instead. “Naively, I thought: if I take this to the right authorities, they will stop it.” That was when things grew peculiar.

Richard Allen

In 2004 other retailers, including the supermarket giant Tesco and even Amazon, complained formally to the government that the LVCR loophole was damaging their business. The government, inexplicably, did nothing. The big retailers soon began to fold under the price onslaught, one after the other, and each set up their own offshore fulfilment centres. HMV, one of the biggest bricks-and-mortar sellers of CDs and DVDs, told the BBC in 2005:

“We resisted that for as long as we could but we realised that if we were to try to compete on the same level playing field then we would have to try to get . . . that advantage as well.”

That was some level playing field: anyone unwilling to go offshore was locked out, on a factor that had nothing to do with quality, productivity, good service – or anything else related to having a healthy economy.

The story of Allen’s long, hard battle for a level playing field is long and complex – it’s covered in some detail here – but in essence, the UK Treasury fought doggedly to protect the tax haven loophole, refusing to engage seriously with his arguments, stonewalling, furnishing him with false statements, even at one point asking him to bring his passport to a meeting at a secret location in London arranged by a mutual friend of a top official. Allen asked how it was possible the tax authorities could be unaware of 25 shipping containers travelling each way between Portsmouth Harbour and the Channel Islands every day and was told that “sometimes things get missed.”

This wasn’t the only VAT loophole being protected by the UK government for questionable reasons, either. A few years earlier the telecoms providers BT and Freeserve had gone to court over their having to pay VAT while their competitor AOL escaped the tax (not via LVCR but for other reasons), giving AOL “a powerful competitive advantage over UK internet service providers,” as Freeserve put it. The company’s chief executive John Pluthero went further, estimating that the UK government might lose £100 million through this loophole, adding that “you really have to wonder what it is AOL has over this government.” AOL won the case in 2003.

In 2007, Allen’s Freak Emporium finally collapsed. He might have given up but for the fact that he had recently written to the European Commission, which wrote back offering to take up his case. The UK government then fought the Commission too – including telling them untruthfully that the scam had been stopped – but the UK had no argument, and had to concede. In 2011, they closed the LVCR loophole.

But Allen’s victory was bittersweet. By then, over 1,600 UK record shops and online stores had gone bust, part of the wider destruction of high streets in the UK and elsewhere, in the face of larger players using a tilted playing field to dominate markets.

Soon afterwards, the Sunday Times rich list estimated that Simon Perrée and Richard Goulding, the founders of Play.com that had grown explosively by exploiting the LVCR loophole, were each worth £160 million. Matt Moulding, who founded The Hut as an offshore VAT-free online sales operation, recently received over £800 million in shares in one of the biggest payouts in UK corporate history.

Failed by the orthodoxy

The lessons from this story are drawn from the UK, but may apply to every country. Here are a few.

- Our inaugural newsletter described how a group of thinkers in Chicago in the 1970s began to popularise ideas that the scope of antitrust should be restricted, by airbrushing out questions of power, economic diversity and the structure of markets, or the wider public interest, and focusing instead only on the narrow questions of the internal efficiency of corporations, and prices and consumer welfare. If consumers did well (as measured by economists, in narrow ways), they argued, then all was well. These ideas remain dominant in the antitrust community, including in the UK and Europe. Allen’s case reminds us of the failure of this approach: competition from the tax haven operators may be good for consumers by providing cheaper tax-free goods and services – but it is terrible for a healthy economy.

- There was nothing economically efficient about the advantages Allen’s competitors had either. First, tax is not a cost or a loss to an economy but more like a transfer within it, so VAT costs to consumers are likely to show up as benefits elsewhere, and benefits to offshore firms likely to show up as losses elsewhere. Second, what is efficient about shipping goods out to the islands, separating them, then shipping them back again? Third, what is efficient about steam-rollering small businesses in favour of a powerful few?

- Many people think competition policy is just about “breaking things up” to foster competition, but this is an error. Breakup of dominant firms is an essential (and woefully under-used) tool, but Allen’s trials make clear that tackling dominant players needs a range of policies – including, here, in the tax arena – to preserve vibrant economic ecosystems. Competition authorities played no role in Allen’s fight: competition policy only interacts weakly with tax policy – such as in cases pursued by the European Commission where tax advantages can be deemed illegal State Aid. They should, but do not, interact at this level.

- The answer here was not just “more competition”– in this case, unfettered competition let the offshore giants steamroller many small onshore businesses – but competition carefully regulated in the public interest.

- Competition is not a natural outcome of “the market” – it is intensely political. The Freeserve official’s question about “what it is that AOL has over this government” – and the UK government’s strange gymnastics to try and keep the loophole open, raise the question of why the UK would actively choose to forego so much revenue, and to see so many local businesses go to the wall, in defence of corporations based overseas and offshore. Lobbying and influence surely played a part. But there is a longer answer, which revolves around a murky and often misunderstood concept known as “national competitiveness.” We’ll return to that subject soon.

- Ponder the geographical implications of this inside any country (here, the UK.) Monopolisation is a centralising force, economically speaking: the winners (the shareholders of Play.com, Amazon, Ebay, for example) tend to be located in wealthy parts of the UK, overseas or offshore, while the losers are spread more widely. So monopolisation implies hidden flows of wealth, from poorer to richer regions. The UK government’s current ‘leveling up’ agenda to help regions catch up with London will fail, without tackling monopolisation. (More on that soon too.)

A last thing from Richard Allen. Following his indefatigable campaigning on VAT abuse, he is now itching for another fight, against a vastly more powerful opponent.

Amazon, the Dungeon Master

For many if not most small businesses these days, one playing field is rigged more than any other: online platforms like Ebay – and especially Amazon. From his business contacts, Allen said, “the number one complaint is ‘when is anyone going to deal with Amazon? They are destroying my initiative.’ ”

One danger is that Amazon sells its own products on its own platform, in direct competition with small (and larger) businesses. But Amazon controls every aspect of that platform, its algorithms decide whose business get shown to customers, and with what priority. It is involved in procurement, delivery, and now physical stores. It doesn’t necessarily show customers the best prices: it shows them the ones that are most profitable for Amazon. It can kick suppliers off its platform on a whim, and its awesome power enables it to levy outsized fees, like private taxes, on all the players that sell on Amazon, including large companies. Falling between regulatory gaps, this marketplace avoids proper regulation, and is thus rife with fraud and abuses of power.2

Many years ago, Allen played the role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons (DnD), where friends sits around and the Dungeon Master presents them with an adventure, through a series of choices. (“The wizard points his gnarled finger towards you: what do you do?”) The players must abide by the rules set by the Dungeon Master: the only alternative is not to play. There’s a parallel to be drawn here, he says.

“If you run an online marketplace, you can see everything and nobody else can see it,” Allen said. “Amazon is the Dungeon Master but unlike a game of Dungeons and Dragons, they also have a stake in the game as a player. You are in their Dungeon – and because they can see everything, they can use that information to further their role as player in the game. Basically they are able to cheat.”3

Imagine the outcry if a giant trucking firm owned all the main roads on which it and its competitors did their business – and crushed them at will. There is nothing natural about this kind of control: why should we accept this behaviour from a giant digital company?

Change is coming

Amazon is still wildly popular, because of its (internal) efficiency and apparently low prices. But the ground is now shifting, fast, at last.

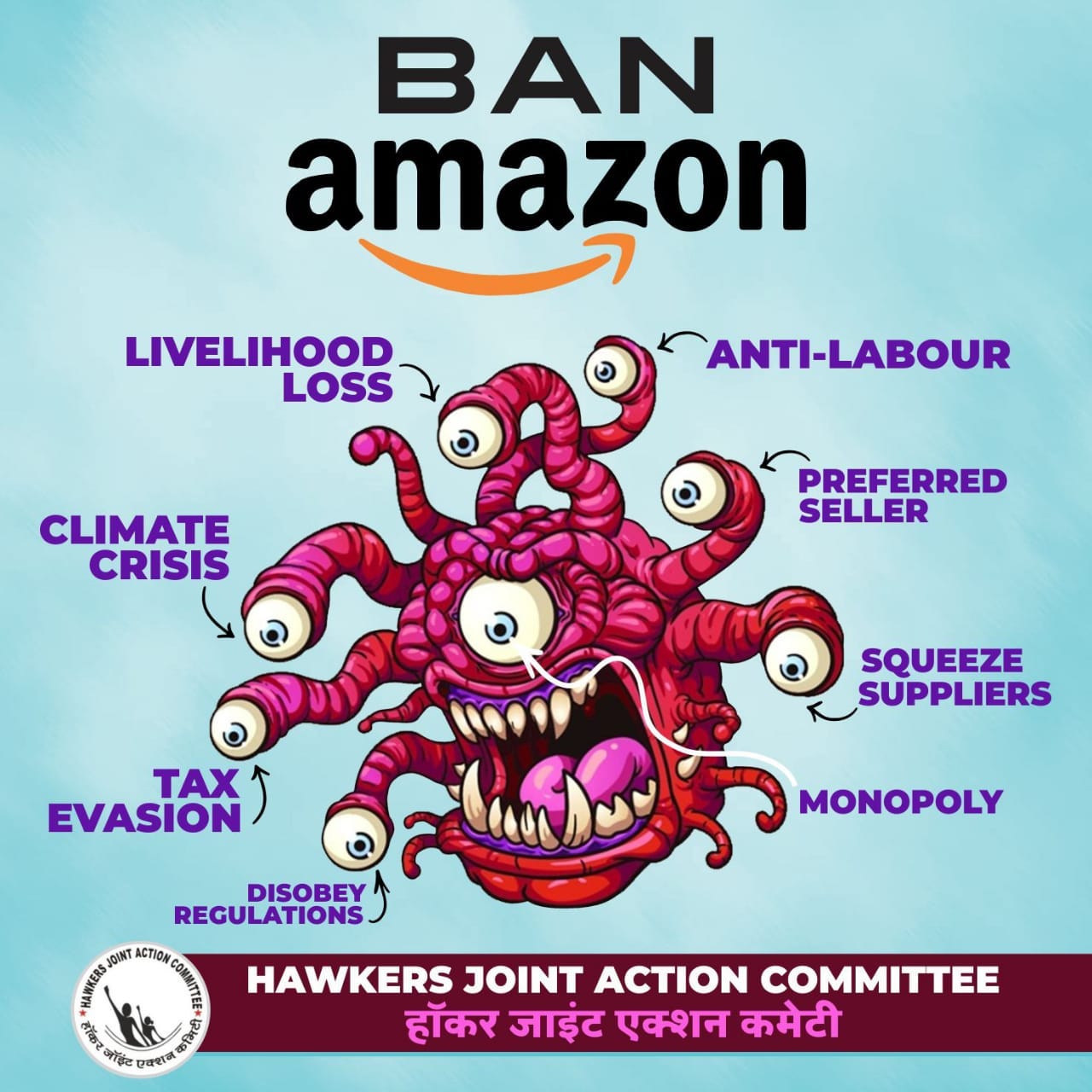

Amazon workers in Alabama are fighting to unionise, with top-level political support. The Make Amazon Pay campaign has garnered wide political support, in a number of countries. Campaigners in India even seem to have posed Amazon as the terrifying Beholder from Dungeons and Dragons, with a death ray in every eye.

Resistance is building fast, most rapidly in the United States. For a good illustration of the growing fightback see this new article in the New Yorker, about a Kansas bookshop’s fight with Amazon and how the company sucks wealth out of rural America, including a link to a publication entitled How to Resist Amazon and Why.

Allen proposes an Online Marketplaces Act in the UK, an Act of Parliament to fill in gaps and uncertainties in UK law which would:

- Define what constitutes an online marketplace and set minimum standards

- Prohibit online marketplaces from selling on their own marketplace.

- Prevent owners of marketplaces leveraging marketing data for their own advantage.

- Ensure that tax is paid, is fair, and applied equally, so as not to distort competition. Marketplaces would be the ultimate guarantors of sales taxes.

- Ensure that rights upholding consumer safety, intellectual property and recycling are satisfied either by the seller or, failing that, by the marketplace as the ultimate guarantor of such rights.

- Put in place rights and protections for the many small businesses and individuals that now rely on such online marketplaces for their income.

- Prevent the platforms from punishing “dissidents” or potential competitors, just as banking legislation protects customers from predatory activities by large banks.

He isn’t alone in such ideas. Lina Khan’s classic 2017 paper Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox contained a set of landmark ideas, and these and others were reflected in a key recommendation in a US House investigation of digital markets last year. These ideas – we’ll return to them more fully in future editions of The Counterbalance – may have seemed utopian even a year or two ago, but the ground is now shifting so fast that we predict they will become mainstream.

Be the first to comment