The Catalan language cannot be commodified, so is of little interest for the EU or the international corporations it serves

Toni Strubell is a former MP in the Catalan Parliament, journalist, and author of What Catalans Want

Núria Bassa Camps is a Catalan writer and photographer

The authors’ gratitude to sociolinguist Miquel Strubell for advice given regarding this article

Puede leer este artículo en catalan aqui

The issue of the Catalan language and the legislation that defines its legal status is a recurrent subject of bitter controversy in Spanish politics. It is now a burning issue again in the Spanish parliament, where accusing the Catalans of “imposing their language” has long been a unionist vote-winner. To prove that Catalan is not the imposed language, a Catalan Republican MP, Gabriel Rufian, this week attempted to speak in Catalan at the Madrid Parliament. On being banned from doing so on two occasions by the speaker, he was able to prove his point that Catalan is not only a language that is not imposed, but one that is effectively forbidden. And though at first sight this issue may seem to lack relevance for non-Catalan speakers, Catalonia has now become a sensitive scenario to permit us to calculate how efficient or inefficient EU legislation is as a guarantee for the minoritised “stateless” languages of the European Union. We fear that once the hypocrisy and mealy-mouthed statements of the EU spokespeople have faded away, the credibility of the EU as an institution offering effective protection for minority languages is null and void.

A little background information

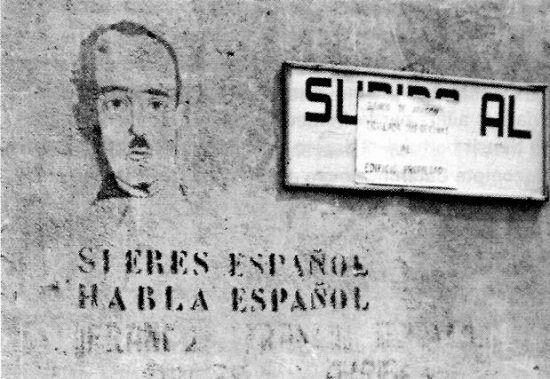

As is generally known, Catalan was forbidden during the Franco regime (1939-1975). It was forbidden in the administration and in schools as well as at the public and official events that might bestow it with prestige. On Franco’s death, the 1978 Constitution appeared to open the door to the respect for languages other than Spanish (Castilian) in the territories where they are spoken. However, it continued with the all-important precept of keeping Spanish as the only official and obligatory language of the State. All that regional languages were offered was a theoretically “co-official” status and different degrees of presence in education. Rarely has this situation led to the full adoption of the language by non-speakers as occurs amongst immigrants with languages that are official statewide.

Despite the Constitution’s non-committal references to the need to protect these languages, they often got little more than “also-ran” status. In the case of Catalan, not only was there no effective recognition of the unity of the language, giving rise to non-academic splinter definitions in Valencia, but, more importantly, the only really obligatory language in Catalonia continued to be Spanish. Catalan, though increasingly present in education, often got a merely ancillary role in key areas for its modern advancement such as technology, big business, and the law courts. This legal framework was a hotbed for future disputes fanned by an age-old inertia in which Spanish was always seen as “the” language and Catalan portrayed by some unionists as an oppressive imposition in areas such as education. In other words, while Spanish was to remain unquestionably compulsory, Spanish-speakers in Catalonia – except for requirements in public posts and some private ones – could conduct their lives in Catalonia as if Catalan did not exist. The differences in status with “State” languages was thus immediately evident.

The field in which this issue created most controversy was education. The Wert Law introduced by the Partido Popular in 2013 put limitations on the consideration of Catalan as the medium of instruction, as had been respected for several decades. Logically, in a country with a high proportion of students from Spanish-speaking homes, schooling in Catalan was the only way a general knowledge of the language could be guaranteed.

In answer to those who say that Catalan pushes Spanish out of the way, repeated surveys show that on the whole Catalan kids not only speak Spanish better than Catalan, but also do so at least as well as kids living in monolingual areas of Spain. Yet this question has sometimes become a bone of contention. It flared up with particular passion as the Catalan Parliament started to debate the 2006 Statue of Autonomy. Opposition to the reinforcement of the status of the Catalan language in education gave rise to the political party Ciudadanos that centred its discourse on the alleged rights of Spanish-speakers. It helped to create an atmosphere that eventually culminated in the Wert Law. Now the new Celáa Law, due to be passed in the coming months, seeks to set back the clock and restore the situation in which Catalan is again allowed a leading role in education in Catalonia. But the question remains: will this step truly give Catalan the necessary tools to survive? Is co-officiality in education enough to ensure the language’s survival? Or are there other greater threats facing Catalan and, indeed, all minoritised languages across the EU today?

The Real threats facing Catalan

According to UNESCO, a language presents a situation of vulnerability and is considered endangered when the number of speakers becomes reduced and there is a high risk of losing the language in favour of a more dominant language that replaces it. The Catalan-speaking countries in Spain (chiefly Catalonia, Balearic Islands and Valencia) have for 300 years suffered a linguistic crusade fuelled by the Bourbon monarchs’ self-proclaimed “right of conquest”. There has been a relentless ongoing persecution against the Catalan language and an unflinching will to impose Spanish in its place. With the advent of democracy, had there been a will to do justice, victims should have been given back what totalitarianism had taken away. Spain’s new democracy failed to restore a situation of linguistic normality in the Catalan-speaking lands. The aim to replace the Catalan language with Spanish, albeit more subtly disguised, remains fully valid.

The conclusions of this year’s InformeCAT, a report published annually by NGO Plataforma per la Llengua on the situation of Catalan, are significant in this context. It offers distressing data on the future of Catalan, hitherto seen as the flagship of Europe’s minoritised languages. The report reveals, for example, that in big cities such as Barcelona and its larger conurbation area, only 16,9% of the population regularly speak in Catalan. In Valencia the situation is even more dramatic while in the Balearic Islands, less than a third of young people speak mainly in Catalan with other people of their age. Can this surprise anyone when it is a known fact that last year alone 134 regulations were introduced to enforce the use of Spanish over Catalan?

The consequences for the Catalan language of this kind of policy is devastating in both private and public domains. In the former, the example of Catalonia’s major car manufacturers SEAT is especially revealing, being the Catalan enterprise with the highest turn-over. For despite the company’s apparent economic buoyancy, neither the SEAT web page – which informs clients in over 50 languages (including Macedonian, Estonian and Slovenian) – nor their posts and messages on the social media, nor the cars’ dashboard displays, instruction manuals or computer voices, are available in Catalan. And the same could be said about the products of thousands of other enterprises in Catalonia despite a law “guaranteeing” Catalans the right to receive all amenities in their own language, as occurs in all EU states in relation to other languages with similar numbers of speakers. Catalonia is the only territory in Europe where such widespread disrespect for the law is rampant (90%). In contrast, practically no sanctions are applied to correct the situation. In fact, Catalan consumers, despite current legislation, have less than 10% of products available to them labelled in their language. The State does not lift one finger to enforce the law. Not only in the case of SEAT but in countless other enterprises with similar linguistic protocols.

Things are even worse in the public sector. For example, if we take a look at public money invested in the film industry in Catalan and Spanish, the disproportion is astronomical. Since 2013, the Spanish government has poured as much as €385M into films made in Spanish, but not one euro into those made in Catalan. Another blow for Catalan has come with the massive popularization of distributor platforms such as NETFLIX that almost completely ignore the language. Despite the fact that 331 of the films currently offered by Netflix have dubbed versions in Catalan, none of these versions are available on the platform. This comes in open defiance to a Catalan law that obliges distributor companies to guarantee that all films screened in Catalan are made available under the same conditions other languages are offered in (Spanish, English, French etc.). This legal requirement is widely ignored by distributors such as Netflix despite the fact that it is considered a serious offence. In theory, the Catalan government’s Ministry of Culture should be fining those skipping the law. Yet no companies have been fined so far. How can the EU expect Catalan to be able to compete in such a strategic field under such unjust conditions?

Indeed, the EU institutions seem not to care less that Catalan suffers severe discrimination with regard to languages with State-backing. An example of this is the treatment bestowed on the broadcasting capacity of the Catalan Audiovisual Services Corporation of Catalonia (CCMA). In the 1990s, CCMA radio and TV broadcasts reached Catalan homes north of the Spanish-French border thanks to relay stations installed in the area by two associations. However, when the signal of the repeaters was made redundant with the implementation of DTT and the consequent analogue shutdown, the Spanish and French governments knowingly obstructed further interstate media reciprocity in Catalan. The EU did nothing to prevent this despite the fact that Spain had ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages which specifically requires signatory states not to limit cross-border media exchange in lesser-spoken languages.

Another serious limitation for Catalan occurs in the field of technology. Although Catalan is very much present on the social media (it is the 10th EU language in number of tweets, 9th in number of twitter users, and 5th language worldwide in number of tweets per user) companies like Amazon, Apple, Samsung and Google fail to include it as a language option in their voice assistants. None of the 32 assistants on the market – including Alexa, Siri, Google Assistant, Google Home, Bixby and Cortana etc. – include the option of Catalan while in Switzerland, for example, Google goes as far as to offer clients German, French, and Italian options with Swiss idiosyncrasies to boot. The Siri assistant offers users about twenty languages, including Finnish, Hebrew, Danish and Norwegian, all languages with fewer speakers than Catalan. Not being an official EU language leaves Catalan and other minority language speakers out in the cold at a time when technological discrimination increasingly marks the difference between the survival and extinction of languages. For although 71·5% of the inhabitants of Catalonia believe not enough is done to protect Catalan, Spain continues to be is the only European state that has refused to acknowledge an official state-wide status for a language with as many speakers as Catalan. It is also the only country to have barred a language of this size an official status within the European Union, despite agreements between Spain and the EU institutions, which have not been implemented.

As regards the Public Administration and the use of Catalan by civil servants – a practice demanded by 90% of the population – the tale of discrimination continues. Many civil servants in bodies such as the National Police, the Civil Guard and the Justice system are unable to express themselves or write in Catalan. Both for Spanish civil servants, and indeed for the population at large, the only language that it is obligatory to know in Catalonia is Spanish. The number of complaints against policemen for linguistic discrimination against Catalan-speakers has increased dramatically in recent years. This is significant because reported cases of language discrimination at the hands of civil servants are only the tip of the iceberg because many cases are never reported.

Many more cases could be given from this year’s InformeCAT to highlight the threats facing Catalan today. Yet, however much supporters and critics may see the new Celáa Law as a tool to restore or impose Catalan in schools, experience tells us that schooling alone holds no magic wand to ensure the future usage and social status of the Catalan language in the age of globalization. OK, so now the way finally seems to be open to make Catalan the core language of education in Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands. But there are dozens of other vital fields in which urgent action is called for to guarantee the future of Catalan and other minoritised languages. On not being officially recognized languages, the European Union institutions will have no qualms about turning a blind eye on the further minoritisation – even the disappearance – of these languages in the future. After all, and in all probability, it will be the pampered official languages of the State members that will be benefited. Cultural genocide they call it, isn’t that right?

Núria Bassa, Toni Strubell

Please contribute to Brave New Europe, a media offering direct insight into the Catalan and Scottish people’s struggle for self-determination and democracy against neo-Francoist Spain and neoliberal Europe

To donate click here

Be the first to comment