It seems a puzzle why, at its March 7 meeting, the European Central Bank indulged in sedate tinkering despite the mounting risk of a damaging eurozone recession. The puzzle has a simple answer. The ECB has reached both political and technical limits. It offers mainly words, in particular a recurring promise to aggressively use its “instruments” if economic weakness “persists.” Left with no options, the ECB must define the problem as lying in the future, not in the present. Hence, always behind the curve, it hemorrhages credibility.

Ashoka Mody is Charles and Marie Robinson Visiting Professor in International Economic Policy, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. Previously, he was Deputy Director in the International Monetary Fund’s Research and European Departments.

Cross-posted from Econbrowser

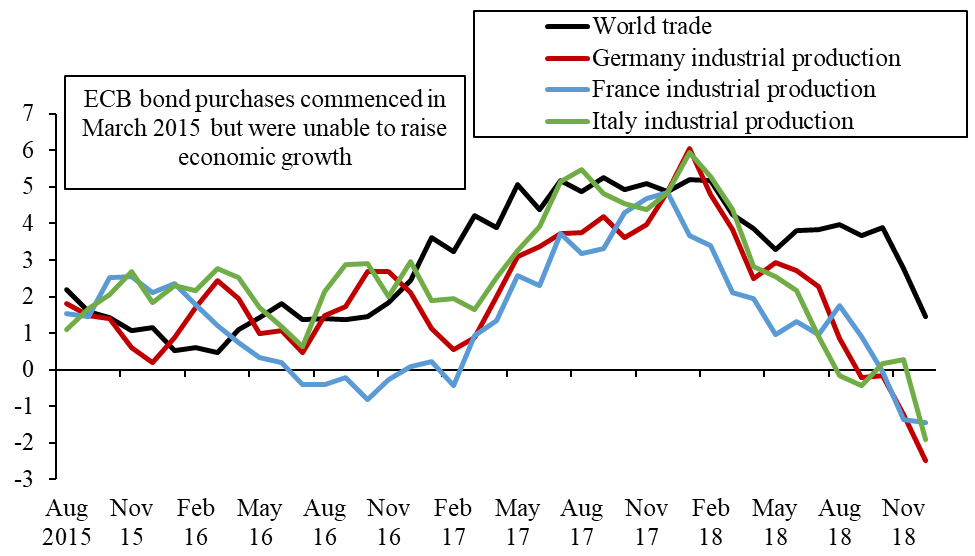

A rapid economic slowdown was already evident when the ECB’s Governing Council met on September 12-13 last year. World trade growth had slowed since the start of the year—and eurozone growth, perennially dependent on international trade, had predictably decelerated. The slowdown was sharpest in the three largest eurozone economies, but the growth momentum was petering out everywhere. The evidence was not lost on the Governing Council, which coyly noted that risks to economic growth had “tilted to the downside.”

Figure 1: Eurozone economic growth marches to the drum of global trade (3-month moving averages).

Thus began the latest cycle of kicking the can down the road. The Governing Council’s members expressed confidence that the “underlying” economy remained strong. They persuaded themselves that “broad-based expansion” was set to continue, and “inflationary pressures” would soon defeat the deflationary tendencies. Thus ignoring the “downside risks,” the Council acted on its optimistic assessment. The decision: asset purchases under the quantitative easing (QE) program, initiated to reduce long-term interest rates, would end in December.

True to that promise, the ECB ended QE in December, thus tightening monetary policy just as recession became a real threat.

The bad news kept coming. By early this year, Italy and even Germany seemed to be sinking into recession. At their January 23-24 meeting, members of the Governing Council said they were surprised. Growth indicators, they now noted, had taken a turn for the worse and “the near-term growth momentum would likely be weaker than previously anticipated.”

The poorer outlook did not justify easier monetary policy, the Council concluded. Such a change in direction was “premature.”

No, such denial and delays are not standard operating procedure for central banks.

U.S. economic growth also slowed in the second half of 2018, especially in the fourth quarter. Even so, U.S. GDP growth, at a more than 2 percent annual rate, was significantly higher than the less than 1 percent growth pace in the eurozone. And the possibility of a recession in the United States seemed remote.

Yet, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), recognizing the economic deceleration, dropped its plan for “further gradual increases” in its policy interest rate. FOMC members also concluded that selling the assets acquired through QE would push interest rates up and therefore they indicated that they might stop the sale of those assets. In late February, in his testimony to the House Financial Services Committee, Fed chair Jay Powell reiterated that the drawdown of the Fed’s assets would likely end by year-end.

The Fed’s easing of monetary policy was greeted by a rise in global stock prices, reinforcing the Fed’s claim as the world’s central bank.

The Fed remains effective because it operates on the risk management principle. As Chairman Alan Greenspan famously said, the time to take action is when an elevator is in free fall, not after it has crashed. The Fed’s January decision was very much in that spirit. It chose to ease monetary policy stance from a position of relative strength. The contrast with the ECB was striking, which simultaneously tightened despite facing much bleaker economic prospects.

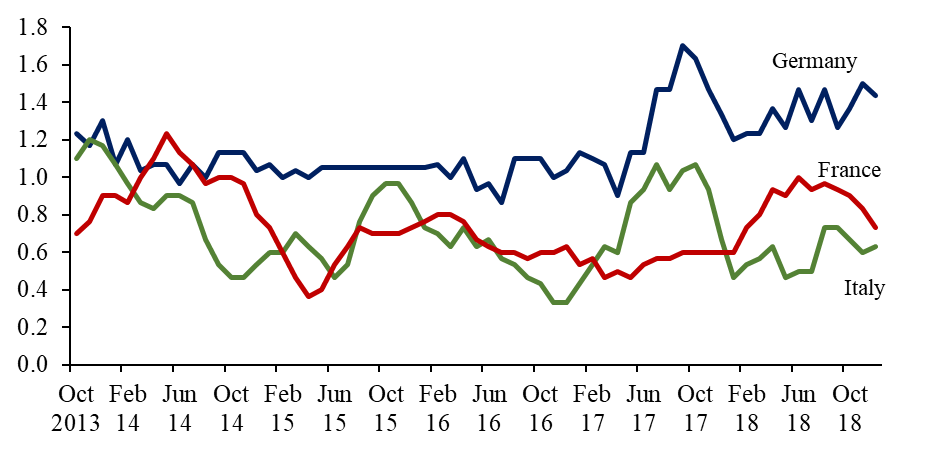

The ECB, riven by conflicting national interests, always acts late, often too late. The northern eurozone countries, with their higher inflation and growth rates, perceive less need for monetary stimulus and so oppose ECB measures to reduce interest rates. They held back eurozone QE in the crucial 2012-2014 years, when large parts of the eurozone—especially Italy and France—fell into a recession and a deflationary psychology. Italy’s “lowflation,” in particular, has kept its real (interest-adjusted) inflation over 2 percent, which is much too high for a country with zero productivity growth.

Figure 2: Italy and France in lowflation trap (Core inflation rates, 3-month moving averages) Note: For Germany, an unusual spike in inflation from June to December 2015 has been omitted.

Now, with mounting evidence of impending recession, the ECB is caught in political and technical traps. Bundesbank president and ECB Governing Council member Jens Weidmann has continued to oppose monetary stimulus. In late January, he called for monetary policy “normalization” by selling assets purchased under QE and “phasing out ultra-low interest rates.” On February 27, the same day as the Fed’s Powell repeated his call for patience in raising rates, the Bundesbank’s annual report warned that waiting to raise rates created “risks” and adverse “side effects.”

Held back by such opposition to more stimulus, the ECB has continued to offer its customary cheap talk. Yes, all policymakers rely on cheap talk. But stymied in its actions, the ECB relies particularly heavily on its words. Asked after the January monetary policy meeting how the ECB intends to fight recessionary and deflationary tendencies, ECB president Mario Draghi’s gave his standard response. Domestic economic and, especially, financial conditions, he said, remain “very favorable.” In any case, “We have lots of instruments and we stand ready to adjust them or use them.” Draghi has used these same words since November 2013, when the eurozone began to slip into deflationary psychology. This pattern of repeated denials, delays, and half-measures is the antithesis of risk management.

And because the eventual scale of actions do not match the words, the ECB has steadily lost credibility. Predictions of an imminent rise in inflation have proven false repeatedly. Italy and France are stuck in lowflation despite modest economic recovery in 2017. Businesses and households in these two countries act on the belief that inflation will not rise anytime soon, which causes them to postpone purchases, which keeps inflation low. Spanish inflation, after a brief spurt in 2016 and 2017, is sliding into lowflation territory. The ECB provides little discernible stimulus to economic growth: the timing of eurozone growth coincides with global trade growth, not with ECB monetary policy.

Having frittered away its firepower, the ECB can now do little. Restarting QE will face extraordinary political obstacles. After all, as Draghi underscored, the ECB has already purchased 25 percent of eligible eurozone government bonds. Northern countries are not anxious to buy more bonds of countries that may eventually not repay their debts.

With little choice at the Governing Council’s March 7 meeting, Draghi announced that the ECB would extend cheap liquidity to banks through its much-touted targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs). In past iterations, the weakest Italian and Spanish banks have gobbled up large chunks of such liquidity. Under new regulatory requirements, these banks will require larger liquidity buffers, which will likely prove too costly to build from market sources.

Thus, in effect, the ECB will continue to subsidize banks’ lending. Not surprisingly, French central bank chief François Villeroy de Galhau and his Finnish counterpart Olli Rehn are worried. Subsidizing the lending of Italian and Spanish banks, they recently emphasized, is not monetary policy. The subsidies prop up the weak banks and their zombie borrowers. Weidmann is right that prolonged “ultra-accommodative” monetary policy can have troubling “risks and side effects.”

Moreover, TLTROs are an odd tool to deploy with the economy slowing down and banks, especially in Italy and Spain, anticipating reduced credit demand. This is especially so since the TLTROs will kick in only later this year, by when the recession will likely be deeper and the credit demand even less.

The ECB has also promised it will not raise its policy interest rates until the end of the year. That is an empty promise. Financial markets know that the ECB dare not raise interest rates in any foreseeable future.

For the rest, the Governing Council is still not persuaded that the downturn could “persist.” Members believe that the eurozone economy will hum again later in the year because Chinese growth will pick up, trade disputes will fade, and Germany’s auto industry will surely rev up again. In any case, Draghi repeated, the ECB has “lots of instruments and we stand ready to adjust them or use them according to the contingency that is produced.” What instruments?

Meanwhile, the latest Chinese economic stimulus can only modestly delay an inevitable slowdown from the country’s historically unprecedented stretch of high growth. Even Chinese authorities project slower growth next year. The eurozone’s primary driver—world trade growth—is set to slow in tandem. Poorer trade prospects will weigh down the apparently favorable domestic conditions. Consumption and investment will slide. As growth rates fall and some countries linger in recession, financial vulnerabilities will rise and, eventually, threaten to spiral out of control. Tremors will spread from the Italian fault line.

Long-time ECB analysts have welcomed the Governing Council’s March 7 decisions, but the more discerning financial markets have barely took note. Analysts have had their expectations beaten down by the ECB’s long-standing niggardly policy stance. They, therefore, are inclined to cheer any change that has a faint prospect of helping. Investors, in contrast, have their money at stake and recognize that they can expect little, if anything, from the ECB.

For the eurozone, a coordinated fiscal stimulus is the only option to prevent a long-drawn recession. Hence, not just to dodge the likely recession, which could morph into a crisis, but also to achieve more robust long-term growth, the eurozone needs a coordinated surge in spending that invests in the future. The rationale for such a policy course is reinforced by the economist Antonio Fatás’s warning: failure to counter recessions and crises causes unused resources to atrophy and, thus, weakens long-term growth potential.

But can eurozone authorities give up the encrusted identification of a good European with the practice of fiscal austerity? Make no mistake, aside from its jumble of words, the ECB has nothing else to offer going ahead. Relying on an ECB miracle and holding back a fiscal stimulus will inflict more wounds on Europe’s deeply scarred economics and politics.

Be the first to comment