The Western elites are so busy satisfying their ineffable greed that they are precipitating their own military decline

Cross-posted from Aurelien’s Substack

Before the War started, most people were vaguely aware of them: they would point excitedly to the sky, perhaps. When the fighting started they were simple, delicate machines with a short range, and capable of little more than reconnaissance roles, but very quickly they evolved to support ground troops and even to carry out bombing raids, with heavier and heavier payloads at increasingly long ranges.

I am, of course, talking about aircraft in the First World War: what did you think I was talking about? Drones? There’s an important point there, because whilst the technology of drones is improving all the time, and involves relatively small amounts of incremental investment, the technology of combat aircraft is now extremely mature, important advances cost a fortune, and they might not even work then.

My suggestion in this essay is that the technologies that the West, in particular, has historically relied upon for combat, are becoming more expensive and complex by orders of magnitude, and that they may indeed be approaching the point where further development isn’t cost-effective. On the other hand, much newer technologies (notably, but not only drones) may turn out to be less revolutionary than some of their fans believe. I argue this not from the perspective of a weapons technology geek (or fetishist, for that matter) but as someone who has from time to time been involved with the practical and political side of force structures and military equipment projects. I’m going to set out what I think the situation is, and then look at the resulting political and strategic consequences after what seems an inevitable western defeat in Ukraine. In some senses, this is a continuation, at a lower level of detail, of my essay of a couple of weeks ago, but here I’m mainly talking about doctrine and equipment.

The development of military aircraft technology between 1914 and 1945 was like nothing seen in the world before or since. Blériot managed to cross the English Channel in 1909: ten years later, Alcock and Brown crossed the Atlantic in a converted Vickers bomber. Air power had already made its mark on the War itself, with the first examples of photo-reconnaissance, close air support and strategic bombing, and almost as soon as the war was over, theorists began excitedly to talk about winning the next one with a few days of aerial bombing, which would bring surrender at a trivial cost in lives and money.

That didn’t happen, but the reality was startling enough. Technology always evolves rapidly in war, but in this case it evolved at breakneck pace in peacetime as well, and the corollary was that an aircraft might only be in service for a handful of years before being replaced by something substantially better. For example, the Hawker Hart, the last biplane light bomber used by the RAF, and with outstanding performance for its time, was introduced in 1930. Almost a thousand were built, but within a few years it had been rendered obsolete by new monoplane aircraft. Even by the time production began, designs for jet-powered aircraft had been drawn up, and the first turbojet-powered aircraft, the Heinkel He 178, made its first flight in 1939, though it never saw service.

Technological change was so rapid because sunk costs were limited, many manufacturers all over the world had the technical capability to produce aircraft, and so production could switch to new variants, or even new models, freely. If the new aircraft or new version became obsolescent or didn’t live up to expectations, there was little problem in retiring it, or relegating it to secondary roles (as happened to the Hart). By contrast, the four-nation European Typhoon fighter programme was first conceived in 1983, and took twenty years to begin to enter service with four European airforces. It is not clear when it will actually be replaced, or by what. Part of the hesitation in the Typhoon programme was, of course, the uncertainty resulting from the end of the Cold War. Yet in practice the investment in technology is now so huge, the number of suppliers so limited, the aircraft themselves of such complexity and the dedicated support so enormous, that countries are always going to be stuck, for good or ill, with what they have decided to buy for a very long time. It’s true that delivering a fleet of modern aircraft now takes so long that better versions can be produced during the manufacturing phase, and it’s normal to have at least one major upgrade, so aircraft can and do become more capable during their lifetime. However, as the story of the F-35 has most recently shown, there are still limits.

As it happens, just about the time that the Eurofighter discussions were beginning, Mary Kaldor published an influential study which introduced the concept of “baroque” military technology. She argued that this technology was rapidly getting out of control, and weapons systems were becoming increasingly expensive and complex, whilst often not being able to achieve their planned objectives. This argument has become increasingly accepted in recent decades, as procurement programmes in many countries run into terrible trouble, and I’m inclined to think it’s an inescapable problem. I’ll try to explain why.

There are weapons (aircraft in 1914, drones in 2022) where developing an improved capability is easy, quick and relatively cheap: there is a lot of what is called “stretch” capability. In such situations, improvements can be introduced quickly, and provide a capability which more than justifies the extra investment. The cost of developing the monoplane Spitfire and Hurricane fighters in the 1930s, to replace the Bulldog, Fury and Gladiator biplanes, was trivial, compared to the enormous increase in capability that resulted. Development of aircraft by all nations during World War II was very rapid, but the incremental gains in capability started to slow down quite quickly. Thus, the Spitfire, was already a relatively complex design when it first entered service in 1938, and went through no less than 24 Marks during its lifetime. But by the end of that period, it was clear that there was little stretch potential left, not just in the Spitfire, but in the monoplane propeller-driven fighters more generally. Fortunately, at that point jet aircraft were coming into service and it was clear that they were the future.

In the first few generations of jet aircraft, also, capabilities improved very fast, and the investment required to move between generations was at least proportional to the increased capability. Major nations could produce jet aircraft by themselves, and in larger states there were often several potential suppliers. (Where collaboration happened, as in the Franco-German AlphaJet, it was usually for political reasons: in the event, the AlphaJet was effectively two different aircraft.) The result was that aircraft had a relatively short service life: the famous F-86 Sabre, produced from1949 in huge numbers, was nonetheless replaced in US service by the F-100 beginning in 1954. As aircraft technology has further matured, the time and cost of development has increased exponentially, such that we have probably reached the point where the marginal increase in combat capability no longer justifies the marginal increase in cost. For example, sheer speed was important up to a certain point, but, apart from specialised niches, it is seldom pursued for its own sake any more, whereas fuel efficiency (and hence range) is still important.

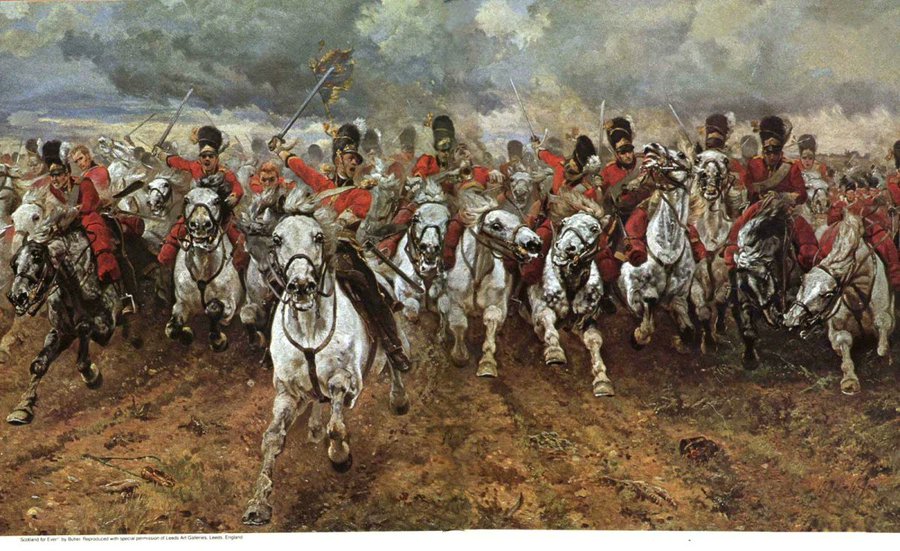

This argument perhaps requires some justification. But let’s start with one simple proposition: in the abstract, the technical performance of weapons systems is largely irrelevant. Weapons exist to fill a tactical role, which is part of an operational purpose, which contributes to the attainment of a strategic objective. It’s quite common for weapons systems to be abandoned simply because there is no task for them any more—battleships are the obvious example— or for that matter to come back into fashion unexpectedly. The classic case of the latter is the Mk 1 horse, declared out of date many times, but used in massive cavalry battles during and after the Russian Civil War, by the Germans from 1941-45, by the French in Algeria and even by the US in Afghanistan.

This is why it’s best not to go gooey-eyed over the technical specifications of new weapons systems without asking how they are likely to be used, and what the opposition will be. To stick with aircraft for a moment, most modern western aircraft are the product of the doctrine of “air superiority,” which means dominating the airspace over the battlefield such that your own forces could operate freely, and you could use your airpower to attack the enemy. As the range and endurance of fighter aircraft increased, this elided into “air defence” where the purpose was to prevent the enemy air force from bombing and damaging your own assets, usually by first defeating the fighters that would be sent to protect them. This is what the Battle of Britain was about: the RAF’s target was the enemy bombers: the fighters were an obstacle to be surmounted first. But as early as that episode, it became clear that the technical characteristics of the aircraft were only one part of the whole capability. Without radar, fighter control facilities and radio, the RAF would have had a much harder time of it, no matter how wonderful the individual aircraft.

But developing aircraft for these roles implies a whole host of subsidiary assumptions about how a war will be fought. It implies that the enemy will play the same game, and seek to dominate the airspace over the battlefield with aircraft, use aircraft to attack battlefield targets, and also targets in your country. For a long time, this was a reasonable assumption, and even towards the end of the Cold War, it was thought that the Soviet Union would send manned bombers to attack targets in western Europe, escorted by high-performance fighters. Although, even then, engagements would have been at some considerable distance (the “short-range” AIM 9-L missile of the 1980s had a maximum engagement range of 15-20km) the concept was essentially the same as in 1940. So aircraft like the Typhoon and the French Rafale were originally designed for long range combat (“dogfights, if you accept that the dogs can’t actually see each other) in a putative war with the Warsaw Pact around 2010.

The inherent conservatism of military thinking, as well the sheer uncertainty of the future, means that the default choice for a new weapons system tends to be an improved version of the previous one. So we read of the “threat” of new sixth-generation Chinese fighters with advanced stealth capabilities, and this “threat” is predicated on the assumption that improved versions of US and Chinese aircraft will engage in massive duels for air superiority over the Taiwan Straits. In addition, of course, once you have an improved aircraft, even if it was originally conceived as a fighter, you can adapt it to do other things. So the Rafale has actually been employed since its introduction almost entirely in ground support roles, in the Sahel, Afghanistan and Syria. And finally, politics plays a role as well. The ability to field even small numbers of advanced fighter aircraft is both a political statement to a potential enemy, and a sign of the assertion of a certain military status in the world, just as the possession of Main Battle Tanks means you are a serious Army. All of this tends, as I have just suggested, to favour producing a more advanced version of what you already have.

One way in which you can attempt to cater for future uncertainties is to design an aircraft that can do a number of different things. Historically, this was not the case, and air forces even a generation ago featured a far greater variety of aircraft than we find today. (At the end of the Cold War, the RAF operated thirty-odd main types of aircraft.) Even so-called “multi-role” aircraft —the tri-national Tornado was originally called the Multi-role Combat Aircraft, or MRCA— tended in practice to be built as different variants of a single original design. In theory, multi-role aircraft, like multi-role ships, are a great idea: in practice often less so, because different roles require different characteristics and impose different limitations. As far as can be seen, many of the problems of the F-35 project have their origins in the resulting design compromises. When you think about it, asking different variants of the same aircraft to be able to land vertically on the decks of carriers and to carry out air superiority missions against advanced opponents can only be qualified as ambitious.

It’s at least arguable, therefore, that the useful development of manned combat aircraft is now coming to an effective halt. Obviously, new variants and even new types will continue to be developed and introduced, but they will be bought in increasingly smaller numbers for financial reasons, take forever to design and bring into service, be loaded down with ever more sophisticated electronic gizmos, and be more and more difficult and expensive to maintain. And they will be effectively irreplaceable during a campaign: lose two or three against rudimentary air defences in an operation somewhere, and you might have to wait years for replacements. Much more than is often realised, air forces today are single-shot enterprises.

Yet the bone-crushing inertia resulting from generations of strategic theory and practice still perpetuates the idea of the manned aircraft as the weapon of choice. Until perhaps a decade ago, this would have been a defensible option. But, like aircraft in 1914, drone technology, combined with networked systems, is developing extremely fast, and is likely to eat at least some of manned airpower’s sandwiches quite quickly. Why? Well, first of all, drones, like aircraft, are an enabling device: a platform. Without cameras, fire synchronisation with propellors, navigation aids and most of all weapons, aircraft would have remained a curiosity. So, whilst the technical characteristics of drones are improving rapidly, what really counts is the uses to which they can be put, and the weapons and sensors they can carry. These are expanding and improving rapidly all the time as well. Already, we are seeing the Chinese using small drone fleets commanded by manned aircraft, and this may well be the pattern for the future.

The point is not that This Changes Everything, which tends to be the unthinking reaction of techno-fetishists, but rather that countries which are not hindered by the dead weight of the efforts of generations of airpower enthusiasts are likely to react more quickly and creatively to the new technologies. Certainly, it’s striking that the West as a whole, although it has used drones in various past conflicts to attack individual targets, doesn’t have, and doesn’t seem able to develop, a strategy for using them properly at scale. And of course the antics of the This Changes Everything lobby, with a lot of money in play, don’t help either.

By contrast, neither Russia nor China have the same history of manned aircraft dominance. The Russians did, it is true, make extensive use of ground-support aircraft in the Second World War, but this was very directly in support of Army operations, and subordinate to them. Likewise, the Soviet Union developed a national Air Defence Command as a separate branch of its armed forces (it was not absorbed into the Air Force until 1998.) But it featured very large numbers of missile systems, as well as radars and command and control systems, and it seems as though the aircraft themselves, whilst numerous, were essentially flying missile platforms, vectored onto their targets by ground controllers.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, missiles—mentioned for the first time here in the preceding paragraph, you’ll notice—have been a Russian preoccupation for a very long time, although it is surprising how little attention the West, secure in the superiority of its own concepts, actually paid to the fact. From the first experiments with captured V2s and German scientists to the present large and sophisticated arsenal, the Russians have looked on missiles as a primary weapon system, whereas the West, simply, has not. Moreover, rocket systems of all kinds still have a great deal of stretch potential in them, because of possible improvements in range, accuracy, speed, manoeuvrability and payload. And indeed, under the stimulus of war, the Russians have developed sophisticated tactics mixing rocket attacks with drone attacks, including the widespread use of decoys. At the moment, no western power has an equivalent or answer to these technologies and tactics, and indeed, for all the excitement and the announcement of ambitious research and development programmes, it’s unlikely that there will be any.

One reason why countermeasures may never be developed is that it may just prove to be impossible to defend against massive attacks by extremely fast and accurate missiles capable of manoeuvring violently, mixed with various types of drone; some decoys, some designed for defence suppression, still others for direct attack on individual targets, including some selected by the drone itself. The other is that the current financial and conceptual investment of the West in manned aircraft systems is cumulatively massively greater than the its investment in missiles, whether for direct attack or to gain air supremacy, and so a correspondingly massive change of doctrine would be needed. It’s not even obvious that the West could mount programmes comparable to those of Russia, since it would take probably decades to develop the technologies and begin producing the systems, and even then, individual nations, and counting what little remains of the US presence in Europe, could not field enough systems, or devise any kind of collective doctrine for their use. In effect, the West continues to invest primarily in technologies already near their practicable limit, whereas the Russians have put a lot of their investment into technologies where there is still considerable scope for development. In spite of all the talk about combat aircraft for the 2040s (it’s too late for the 2030s) there’s a powerful argument that, in the end, it’s not going to be worth it.

However, it’s worth taking several steps back at this point, and reminding ourselves what the ultimate purpose of the use of these technologies actually is. And that does not amount to “destroying the enemy,” outside video games anyway. Recall, once again, that Clausewitz said the purpose of military action is to give the state extra options for carrying out its policies. By definition, the objectives of a state are going to be political, and, simplifying somewhat, we can say that these options amount largely to obtaining dominance at different levels. Clausewitz also said that the purpose of military conflict is “to oblige our enemy to do our will,” which means that the ultimate target for dominance is the decision-making process of the enemy. There are a number of ways of approaching that objective, which can range from physical occupation of the country, to the destruction of the enemy’s power to resist, to simple intimidation. Clausewitz would have well understood, for example, the potential intimidatory use of the Russian missile force as a way of extracting political concessions from the West, given that the West will have no comparable way of replying, nor any workable defence. More widely, it is pointless for the West to threaten, or even plan for, a military confrontation with Russia, because its forces, built around an outdated concept of warfare, would simply be taken apart.

The novelty of this situation might not be apparent at first sight. Obviously there have been wars between opponents with very different levels of technology, even if the side with the better technology has not always won the battles (think of Isandlwana for example.) There have also been plenty of cases, like the first Gulf War, where the two sides fielded very similar technology, but one of the sides scored a decisive victory. The only relevant modern example I can think of is the defeat of France in 1940, where the new German concept of warfare—popularly if erroneously known as Blitzkrieg— defeated an enemy as well equipped, and as highly motivated, in a few weeks. What was new was not the individual components of tanks and aircraft, but the concept of fast-moving armoured spearheads, avoiding combat and sowing confusion, and the use of aircraft as flying artillery controlled by radio from the ground. This, combined with the forward deployment of anti-aircraft guns, constituted a concept to which, at that stage, there was no counter, and would not be for several years. It is true that if the Germans had continued with their initial plan of a main thrust through Belgium and a diversionary thrust through the Ardennes the battle would have been more difficult, but they would probably still have won.

In that case, as indicated, the advantage was only temporary. In the case under discussion today, it might be as good as permanent. The lessons of drone-intensive network-centric warfare are still being learned in Ukraine, and the situation—and for that matter the concept itself—has not yet finished developing. The Russians had not planned for such a war and were caught off guard. They have been reacting hastily, with the improvisation for which they have always been famous, but they have the advantages of being a single, large nation, with a massive military technological base, and a concept of warfare which, whilst it was still out of date, was far closer to the type of conflict now under way than anything the West has. Just agreeing on what kind of “operational concept” NATO would need to oppose Russia would take years, and implementing it would require top-to-bottom reconsideration of force structures, procurement plans and military training. Meanwhile, of course, the Russians would not be idle.

It’s worth pointing out that the problem goes well beyond the limited case of land-air warfare in Europe, and applies to potential western operations more widely. At sea, for example, the West deploys its navies to achieve sea control, which is to say that you can control the movement not only of commercial shipping, but also of naval vessels in a given area. There were times when direct combat between fleets effectively settled the issue of control. In both World Wars, the British, with US help, essentially controlled surface shipping in the Atlantic. In the First World War, the Battle of Jutland, although won on points by the Germans, nonetheless resulted in British naval dominance of the North Sea. In the Second World War, the Germans did not have enough of a fleet in 1939 to mount a challenge, but they did change the nature of the game by producing large numbers of submarines, notably to target merchant shipping.

Even during the Cold War, fleet-to-fleet actions were no longer really expected, and now, behind the bloviating and the alarmist reports on China, there seems, unsurprisingly, to be little real agreement on what in practical terms western navies are actually for. Well, one habitual use of sea power is for general power projection. Depending on the context, military units can be landed, nationals evacuated, sea-lanes policed (at least in theory), disasters relieved, pirates dissuaded and invasions supported. But the fitting of very long-range anti-shipping missiles to warships like the new Chinese Type 55 Destroyer, means that western naval forces are vulnerable to missiles launched a thousand kilometres away. It’s hard, therefore, to imagine that some hypothetical US/China naval engagement with Taiwan as the prize would resemble any historical fleet action of the past at all. And whilst missiles of this range and complexity are not going to be widely available around the world any time soon, recent experience has shown that relatively cheap, relatively short-range systems can have a powerful deterrent effect on western deployments. Again, it’s the complexity and cost of the vessels themselves, and the time it would take to replace them, that are the real western weaknesses. Most western nations could lose their navies in an afternoon: with the US it would take a little longer. But the overwhelming inertia of the past, and the lack of clarity about possible missions mean that the solutions to these problems, if they exist, are not obvious.

Finally, land warfare has shown essentially the same progression. If you look at an illustrated history of the Main Battle Tank, you will find that between its introduction towards the end of the First World War and the versions that were fielded by the Germans in 1944-45, there were huge advances in every area. By the time of the Tiger II tank, the last heavy model to be fielded by the Wehrmacht we see something recognisably contemporary: not least a weight of some 70 tonnes, with its associated logistic problems. Even the “medium” Panther tank had a weight of 45 tonnes and looks recognisably modern.

This isn’t surprising. Tank designers will tell you that you can optimise for any two of speed, armament or protection, and the rules of engineering and the problems of logistic support don’t change fundamentally. Western tank designs in the Cold War, whatever else you say about them, did follow a certain logic. NATO planned to fight a defensive war on its own territory, so speed was a lower priority than protection and firepower, and logistic support would be facilitated by falling back on its own lines of supply. Thus, the behemoths that were sent to Ukraine, went into a tactical environment for which they were completely unsuited and never intended. It’s not clear that they will be better suited for any future war. The Russians, historically using lighter and more mobile tanks, suffered themselves from drone attacks, but indications are that they have started to use tanks again, quite effectively, not least in combination with new types of land-based drones to provide protection.;

But there’s a good argument that, in general terms, tank design came to a dead end some while ago. The M1, Challenger 2 and Leopard 2 tanks sent to Ukraine are developments (or in some cases not) of designs from the 1970s. A great deal has been done peripherally since then to improve protection, but the speculation in the 1980s about the next generation of tank (140mm main armament, 70-80 tonnes weight) has pretty much remained speculation. And there is some doubt that the “revolutionary” Russian T-14 Armata has been deployed in Ukraine in anything more than token numbers. The problem is, nobody really knows how to use tanks effectively at the moment, in an environment where precise and deadly drone attacks are a threat. In any event, while Russia is currently producing around 300 tanks per year, intended to rise to 1000 by 2028, no new tanks have been produced for the US Army for forty years, and it’s not clear what new western tanks would look like, or even if it is worth trying to produce one. (The proposed British Challenger 3, if it is ever procured, even in the tiny numbers planned, will just be a bigger Challenger 2.)

So it would be possible to say (and I have heard it said) that It’s All Over, and western military dominance is a thing of the past. But as always it’s a lot more complex than that, and the reason it’s more complex has to do with our friend Clausewitz, and his insistence on the higher political purpose of military operations. So long as the military is required to produce outcomes to support political objectives, some way will have to be found to make that possible. Let’s begin, therefore, by considering some of the things that drones and associated technologies can’t do. Because, once again, outside the pages of weapons-fetishist magazines the abstract ability to blow things up isn’t very important.

We recalled at the beginning that the purpose of military action is to get your enemy to do what you want. However, doing what you want requires a political decision by the enemy government, and this is where the problems historically arise, as is the case now with Ukraine. Short of total annihilation and extermination, there will always be a practical limit to the degree of pressure the military can actually exert. If, as in this case, a government which has effectively lost the battle nonetheless refuses to surrender or negotiate, there is only really one certain option: the physical occupation of some or all of the country, perhaps for some time. But to state the obvious, drones cannot do this, even the new land-based drones the Russians are fielding in Ukraine. Drones and associated network technologies can deny access and communications, destroy equipment and infrastructure, and create areas where no military action is possible, but they cannot take and permanently hold ground. Neither, of course can rockets and missiles, however powerful. Only ground forces, and in quite large numbers, can do that. In the case of Ukraine, Russian forces seeking to take and hold ground would anyway themselves be subject to all kinds of improvised attacks from drones, mines and other systems. Drones could help to defend forces once in possession of ground, but that’s about it.

Likewise, reasonably accurate, relatively long-range missiles can keep quite sophisticated western forces at a distance, and in some cases retaliate against enemy targets, but that’s all. Thus, Ansar’Allah in the Yemen has been able to keep western warships at a distance, and stop attacks from those ships being launched against them. But nothing stops the West from coming back with other means of attack. Ansar’Allah, like Hezbollah in Lebanon, has no effective means of air defence. Whilst Hezbollah can induce the Israelis to retreat and then occupy the vacated ground, and whilst it can also bombard cities in Israel with a degree of accuracy, its orientation is necessarily defensive against a first-rate military power. It won battles in Syria supporting the Assad regime, because its opponents were essentially lightly-armed militia. So Hezbollah can oblige Israel to withdrew from Lebanon, but it could not, for example, occupy and hold disputed territory against serious resistance.

Although in the short term, the technologies we have discussed here are of most use in situations of tactical defence, they do not provide any inherent advantage simply because you are a country defending against an attacker. Russian forces have already shown how drones can be used as offensive weapons, and any attack on a western country would be over pretty quickly with the mass use of drones and missiles which, as I’ve indicated, the West has no idea how to counter. Likewise, in Lebanon, the Israelis showed how to use high technology to take apart a resistance movement. They did not try to seize terrain on any scale (which they recognised was beyond them) but rather to force Hezbollah to cease its attacks on Israel, which they did. It all depends on what your objective is.

Which brings us back to where we started, really. New technologies tend to advance rapidly and often in unexpected directions. Mature technologies advance much more slowly, much more expensively and with much more difficulty. The West’s problem is that it has an enormous financial and doctrinal investment in systems of mature technologies, which are increasingly unlikely to ever be asked to perform the missions they were designed for. And it’s not, once more, just a hardware problem: indeed, the majority of the confusion in the West at the moment results from the fact that no-one really knows yet how to make use of the new technologies of drones and their various different capabilities, in a networked war. As we can see in Ukraine, the Russians are still in the process of working this out themselves, and it’s anyway not clear that lessons learned will be applicable everywhere: the Israeli use of drones against Hezbollah was quite different.

I mentioned the Battle of France in 1940 earlier, and I’ll close with a comment by the famous historian and Resistance martyr Marc Bloch in his posthumously published work L’Étrange défaite. “Our leaders,” he wrote “in the midst of many contradictions, strove, above all to recreate, in 1940, the war of 1915-1918. The Germans fought the war of 1940.” Our leaders today are trying to recreate a war that was never fought, but that was widely anticipated, and until recently was the model for military planning. The Russians learned the hard way that the nature of war has changed and is still changing. But for the reasons I’ve discussed I’m not at all sure that the West can adapt in the way that the Russians are trying to. Going back to the start and trying again is never easy.

Be the first to comment