![]()

Chloe Brimicombe, University of Reading; Elliott Sainsbury, University of Reading; Gabrielle Powell, University of Reading, and Wilson Chan, University of Reading

The year 2020 will no doubt go down in history for other reasons, but it is also on target to be one of the warmest on record. And as the climate warms, natural hazards will happen more frequently – and be ever more lethal.

We are early career researchers in meteorology, geography and environmental sciences, and each of us focus on a different hazard. We may not have been as in demand as our colleagues in virology departments, but we nonetheless had a particularly interesting and busy year. So while attention was often focused elsewhere, perhaps understandably, here are some of the meteorological extremes recorded in 2020.

Wicked wildfires

The year began with apocalyptic scenes of wildfires in Australia, fuelled by heatwaves. It was an image that would play out time and time again in 2020.

In June, Siberia began to burn on an unprecedented scale, at the same time as record temperatures which climate change had made 600 times more likely.

Through July and August, the west coast of the US was ablaze. The worst wildfire season in 70 years again coincided with a heatwave, with Death Valley in California recording America’s highest temperature for at least a century – maybe ever.

By September, the Amazon rainforest and the world’s largest wetland to its south, the Pantanal, were on fire. More than a quarter of those fires happened in forest that had not been disturbed by deforestation.

In September 2019, fires in the Amazon had made worldwide headlines. In 2020 there were actually 66% more fires in that month, but attention was elsewhere.

Savage storms

In November, super typhoon Goni made landfall in the Philippines while at maximum intensity, with sustained wind speeds of 195mph. One of the strongest storms to ever make landfall worldwide, Goni directly affected nearly nearly 70 million people, leading to at least 26 fatalities – a number that would have undoubtedly been higher if not for the evacuation of almost 1 million people.

But it wasn’t just wind that posed serious hazards in the western Pacific in 2020. Tropical storms Linfa and Nangka caused significant flooding across Vietnam, exacerbating the problems caused by an unusually active monsoon. More than 136,000 homes were flooded and more than 100 people died.

In the North Atlantic, 2020 was the busiest hurricane season on record, with 30 named storms and six major hurricanes. The single costliest storm of the season, Hurricane Laura, made landfall in Haiti and Louisiana, killing 77 people and causing more than US$14 billion (£10 billion) in damages.

Two major hurricanes, Eta and Iota, caused significant damage in Honduras and Nicaragua. They made landfall in the region in November, just two weeks and 15 miles apart. This is a humanitarian crisis yet one that has received relatively little attention overseas.

Mauricio Duenas Castaneda / EPA

Frightening floods

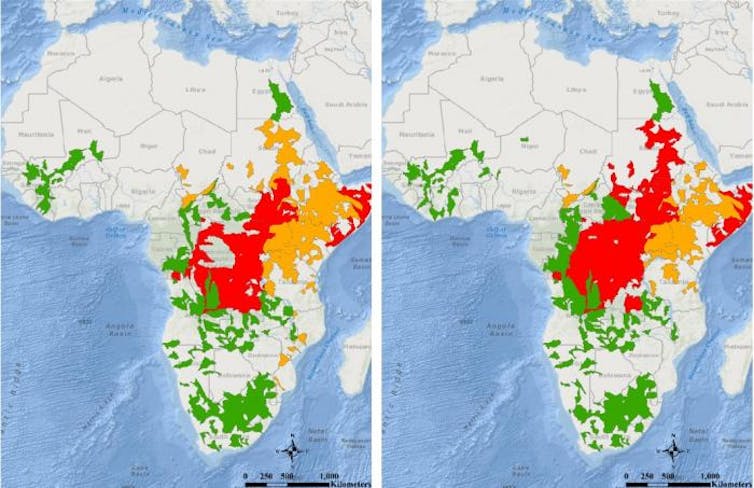

The world’s deadliest flooding this year took place in east Africa in March through May. At least 430 lives were lost and an estimated 116,000 people were displaced in Kenya alone. The previous dry season was particularly wet, and was followed by above average rainfall during the “long rains” of March-May, meaning the vast Lake Victoria had twice its normal rainfall.

NASA / Margaret T. Glasscoe (JPL)

Though the rainfall was predicted in advance, locust outbreaks and COVID meant vulnerable people were already less able to handle the floods and secondary hazards such as widespread landslides and a cholera outbreak. The wet conditions were also ideal for further breeding of desert locusts. When it rains, it truly does pour.

Devastating droughts

Water crises caused by droughts and resource mismanagement were ranked as the fifth highest risk in terms of impact in the 2020 Global Risks Report – greater than infectious diseases and unemployment.

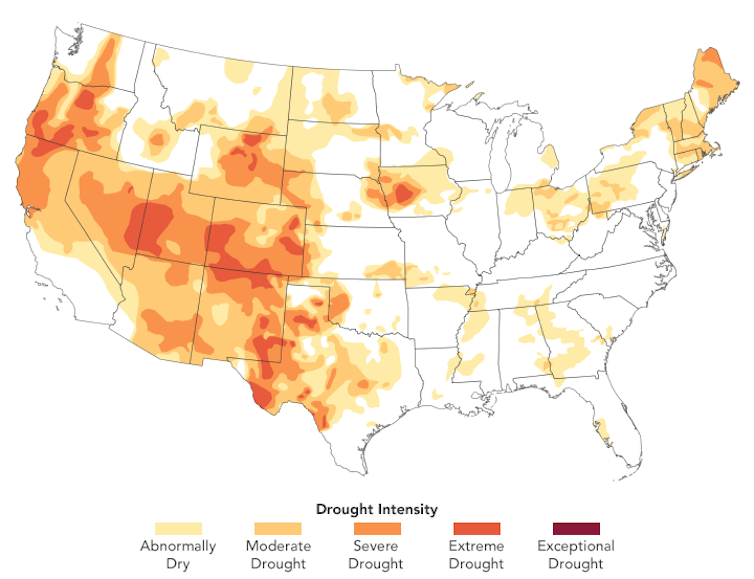

The severe drought across central and western US is the first billion-dollar drought of 2020, contributing to a record-breaking 16 weather and climate disasters with USD$1 billion or more in damages in the US in 2020 alone.

Conditions during 2020 represented the latest phase of a “mega-drought” over the past 20 years. By the peak in summer, a third of the US was in a moderate drought and much of the west was under severe to extreme drought. This coincided with abnormally hot summer temperatures and over 2 million acres of land burned nationwide, further enhancing drought conditions in a vicious cycle.

NASA

The Rio Grande river, a major source of water supply for southwest states, would have completely ceased to flow had water providers not decided to pause existing water diversion schemes. Other impacts included crop damage from one in 50 year dry soil moisture conditions and a rise in dust storms reminiscent of the 1930s Dust Bowl.

Piotr Kalinowski Photos / shutterstock

The latest seasonal outlooks estimate that drought conditions may extend westwards and persist into 2021, complicating the recovery from a difficult year.

Horrendous heatwaves

In May, while a large cyclone struck Bangladesh and eastern India, the north of India experienced temperatures of up to 47℃. This also delayed the onset of the monsoon, impacting farming.

The northern hemisphere summer saw repeated heatwaves, culminating in mid-August. Japan, for instance, had record-breaking temperatures with cities across the country having multiple days at 40°C. In one week, more than 12,000 people were admitted to hospital with heat-related illnesses. Even the UK’s heatwave, accompanied by tropical nights, caused 1,700 excess deaths.

At the start of the summer season in Australia, temperature records have already been broken. It seems the year will go out on an extreme high.

2020 was alarming, unforgettable and traumatic – and not only because of COVID-19. Lethal natural hazards are increasing in frequency under our changing climate, and 2020 is a testament to that.

Chloe Brimicombe, PhD Candidate in Climate Change and Health, University of Reading; Elliott Sainsbury, PhD Researcher, Hurricanes and Post-Tropical Cyclones, University of Reading; Gabrielle Powell, PhD Candidate in Environmental Science, University of Reading, and Wilson Chan, PhD Researcher in Drought Risk, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Be the first to comment