Concerns have been aroused that a new wave of privatisation could be prepared after the European Commission asked KPMG to study the “operational and fiscal challenges” which state-owned enterprises place on the public purse. The contract, due to conclude at the end of this month, raises many questions.

Corporate Europe Observatory is a research and campaign group working to expose and challenge the privileged access and influence enjoyed by corporations and their lobby groups in EU policy making.

Cross-posted from Corporate Europe Observatory

The Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs has awarded a contract worth €800,000 to global accountancy and consultancy firm KPMG to study state-owned enterprises across EU member states, including to encourage “the adoption of best practices regarding the management (including the restructuring and/or privatisation)…”. But this contract, due to conclude at the end of this month, raises many questions. Will this project reinforce the myth that the private sector is more efficient and therefore better at running public services than the public sector, a myth which is held by some at the top of the EU? Will the EU use this project to ‘recommend’ further structural reforms or privatisation processes on EU member states? And is this study even compatible with the EU’s duty to remain neutral when it comes to the ownership of assets, as set out in the EU Treaty?

The contract

In November 2016 the European Commission’s DG Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), awarded KPMG Advisory SPA (the consultancy giant’s Italian arm) and the Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi a contract worth €800,000 to “provide an overview of assets (including State-owned enterprises) owned by the public sector in the EU 28 and encourage the adoption of best practices regarding the management (including the restructuring and/or privatisation) of the portfolio of assets, with the aim of improving the sustainability of public finances and market functioning in the European Union”.

This contract rings alarm bells for various reasons. KPMG and its university partner have been asked to provide overviews of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the EU’s 28 member states including on equity, governance models, investment strategies, and to look at various aspects including “profitability prospects”. It is also asked to provide case studies and draw out the “key challenges” per country for its SOEs. There are one-off references to the quality of services and users’ prices which the consultants should include within the case studies, but otherwise the focus is on mapping the “operational and fiscal challenges” which SOEs place on the public purse.

The awarding of the contract to a partnership which includes KPMG is a red flag. KPMG, one of the so-called ‘Big Four’, provides taxation, accountancy, and audit services to businesses and individuals around the world. It also regularly advises governments on ‘reform’ or ‘restructuring’ (words which are sometimes code for privatisation of public services), for example in water, finance, and other government assets). Meanwhile, via its professional services teams, it is also well-positioned to profit after a privatisation when new market opportunities are created.

KPMG recently hit the headlines as one of a number of companies implicated in the ‘Gupta scandal’ in South Africa. The scandal – which has already led to the collapse of the UK public relations firm Bell Pottinger – included questions over the awarding of big state contracts to Gupta family businesses. KPMG’s South African arm audited Gupta accounts for 15 years and a September 2017 statement on the website of campaign group Save South Africa said “KPMG risks becoming the Bell Pottinger of the auditing profession”. KPMG’s South African leadership team has since resigned and the firm admitted that its South African arm “made serious mistakes and errors of judgement”.

KPMG’s partner, the Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, says it stands for “liberalism, pluralism, and social and economic progress”. It is a private university with “close relations with major corporations and international agencies, as well as their managers and officials”.

Under the terms of its contract agreed in November 2016, KPMG and the University must produce progress reports for the Commission every three weeks, and parts of the research in the project should have already been completed. Corporate Europe Observatory has asked the Commission to see these reports but was refused on the grounds that they “may have a bearing on decisions which have not yet been taken by the Commission”. It’s not absolutely clear what those decisions might be, but it seems a fair bet that the 2018 European Semester cycle – in which the Commission makes ‘recommendations’ to member states about how to structure their economies – could be a focus.

Why does ownership matter?There are many reasons why ownership matters, especially when it comes to public services provision. Privatisation of health services, for example, may extract profits for shareholders by lowering working conditions, providing worse pay, or reducing staff levels, all of which negatively impact on safety and quality of care. Privatisation can also foster greater health inequality as for-profit providers ‘cherry-pick’ lower-risk and higher-paying patients, whilst higher-risk and poorer patients, or those needing emergency care, remain reliant on increasingly under-resourced (as a result of privatisation) public health service provision. Privatisation also undermines democratic accountability of how services are provided. This is not to say that public services provided by public bodies are always perfect, but as documented below, public ownership offers more tools to drive up improvements. Corporate Europe Observatory has recently reported on the creeping agenda of privatisation in the healthcare sector, as pushed at the EU and member state levels. Privatisation channels mapped in the report include: trade deals such as CETA and TTIP; the marketisation of health services which increasingly sees them through the prism of economics; public-private partnerships which enable private finance to get a foothold in public services; and the Economic Governance agenda, including the European Semester’s economic policy ‘recommendations’. |

The European Semester: keeping an eye on member state economies

The KPMG / Bocconi contract needs to be seen in the context of the European Semesterprocess. Seemingly dull and non-political, in fact the European Semester is an important and highly controversial process whereby the Commission undertakes surveillance of the budget and economy of each of the EU’s 28 member states. It provides economic and political “recommendations” to each member state, which are subsequently either tweaked or simply endorsed by the Council, and then passed on to the country in question. If these are ignored the member state may face sanctions. In other words, unelected EU officials draft proposals to tell elected governments how to run their economy. If a member state is in persistent breach of the rules on budgetary austerity (a maximum three per cent deficit is allowed), and the Commission is considering if sanctions should be applied, then the member states’ record under the Semester can be the determining factor.

And things might get even tougher in the future. The high-profile 2015 report ‘Completing Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union’ – also known as the ‘The Five Presidents’ report’because it was endorsed by Commission President Juncker, European Council President Tusk, and other heads of EU institutions – indicated that processes such as the European Semester which aim to create pan-European “convergence” of economic policies should become “more binding”.

The European Semester process was one of the EU’s responses to the 2007-08 financial crisis and is part of its economic governance agenda, which has too often been a by-word for neo-liberalism and austerity, including privatisation. Investigative journalism team InvestigateEurope recently documented how the post-crisis reforms advocated (and in some cases demanded) by DG ECFIN, alongside the European Central Bank and other international actors, have deregulated the labour market in some member states, undermined both trade unions and collective bargaining, and led to greater job precarity due to more use of shorter, temporary work contracts. If workers’ spending power is reduced, that has a negative effect on the overall economy.

Privatisation and the efficiency myth

Reform of SOEs has been a pre-occupation of EU policy-makers for quite some time, particularly since the financial crisis. The Lithuanian Presidency of the European Council hosted a Competitiveness Council discussion on SOEs and their contribution to “growth and competitiveness” in July 2013. The background paper accompanying that discussion includes the line: “In terms of productivity, there is evidence suggesting that SOEs perform considerably less well than private companies.” This reflects a belief, widely held by EU policy-makers, that the private sector out-performs the public sector when it comes to efficiency. But is it true?

“There is no empirical evidence that the private sector is intrinsically more efficient than the public sector.”

That is the striking conclusion of a comprehensive review of hundreds of studies covering all forms of privatisation across many different sectors, conducted by the Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU) on behalf of EPSU, the European Public Sector Union. Looking at nine sectors (buses, electricity, health, ports and airports, prisons, railways, telecom, waste management and water) the report challenged the assumption that privatisation or public-private partnerships (PPPs) can always deliver a given level of service with lower input costs than the public sector. Explanations which explode the myth include the higher costs of private sector investment (because of the need to extract profits for shareholders and exposure to higher interest rates than governments can secure) and conflating private sector cost-cutting with efficiency which are not the same thing. For example, making workers redundant may reduce direct costs for an organisation but creates new costs elsewhere, such as the need for increased welfare spending. Lower wages reduce individuals’ spending power and have a negative effect on the wider economy.

Despite these findings, the privatisation efficiency myth appears to still hold sway among some elite EU circles.

Re-municipalisation not privatisationIn recent years an exciting trend has been sweeping though public services across the world. From New Delhi to Barcelona, from Argentina to Germany, thousands of politicians, public officials, workers, unions, and social movements have been turning back the tide of privatisation and revitalising publicly-owned services. This has most commonly occurred at the local level; recent research by the Transnational Institute (TNI)shows that there have been at least 835 examples of (re)municipalisation of public services worldwide since 2000, across 45 countries. Sometimes this is in response to a privatisation or a proposed sell-off; other times re-municipalisation was driven by the need to improve public services to address people’s basic needs and to respond to environmental challenges. As Eloi Badia, the Barcelona Councillor for Presidency, Water and Energy says:

|

DG ECFIN: ideological blinkers?

Prior to the issuing of the tender for the study on SOEs (eventually won by KPMG and Bocconi), in October 2015 the EU’s Economic Policy Committee (EPC) held a review of two DG ECFIN studies on SOEs in the energy and railway sectors (apparently written by KPMG via a separate contract), and SOEs in new EU member states. The EPC contributes to the Council’s work of coordinating the economic policies of member states, and membership includes officials from each of the EU member states, the Commission, and the European Central Bank. All EPC minutes are confidential and Corporate Europe Observatory was blocked from receiving the minutes of the discussion which took place in October 2015.

A month later in November 2015, DG ECFIN held a follow-up workshop on the performance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in member states, including looking at reforming them. The workshop was web-streamed. Introduced by Anne Bucher (then Deputy-Director General who later left DG ECFIN to chair the Commission’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board), she kicked the event off with the curious observation that “normally” the EU is supposed to be neutral when it comes to the ownership of assets, referring to Treaty article 345 which says “The Treaties shall in no way prejudice the rules in Member States governing the system of property ownership”.

However, Bucher went on to tell the audience that

“If you look back at the last five years… you can see that we had in a number of cases recommendations on SOEs and conditionality on state owned enterprises. In some cases we had it on privatisation and this was mainly in cases where there were issues of fiscal sustainability”.

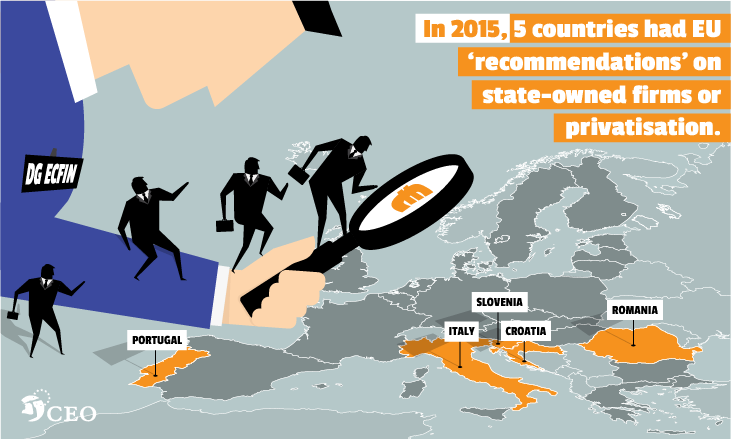

She further pointed out that the 2015 European Semester recommendations included “five countries with recommendations on governance of SOEs or privatisation” eg. Croatia, Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Slovenia. (You can check out a summary of the European Semester ‘final recommendations’ for SOEs in these five countries for the period 2013-17 here. In 2017, Croatia, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, and Cyprus had such recommendations.)

Bucher did not explain how she could justify these recommendations and conditionalities considering the aforementioned Treaty article 345. In some countries these recommendations and conditionalities may reinforce pre-existing national government preferences for privatisation, but it is not clear that this is always the case.

In the 2015 workshop, DG ECFIN then presented two research projects on state-owned railway and energy enterprises, and those in new member states, which appear to assess them only on financial performance.* It took an academic in a subsequent presentation to point out that consumer prices and satisfaction were important criteria to consider, and that SOEs generally outperformed private companies in those areas when it came to the electricity sector.

It is striking the extent to which Commission staff at the workshop defended its approach of looking at privatisation through the prism of profitability, and when confronted with the idea, “Is privatisation the wrong question?”, senior DG ECFIN staff were at pains to argue that it was the right question, and that social welfare issues such as pricing were better handled via regulation, rather than ownership structure. This approach is reflected in the tender eventually won by KPMG and Bocconi which places its emphasis firmly on “public finances and market functioning”.

DG ECFIN refused to release the names or organisations of those who attended its 2015 workshop on SOE performance on the grounds of “data protection”. When Corporate Europe Observatory asked DG ECFIN what discussions it had had with corporate lobbyists on privatisation in EU member states, it told us:

“there have been no meetings of DG ECFIN staff specifically dedicated to privatisation or possible privatisation of state owned enterprises or assets in one of the 28 Member States”.

But DG ECFIN also told us that:

“There have been three meetings identified taking place in Romania, with a general topic of SOE’s economic governance in Romania and the situation of SOEs in the portfolio of an investment fund in view of a review mission under the 3rd Balance of Payments financing programme.”

These meetings were with US investment firm Franklin Templeton.

Romania

The Romanian economy continues to struggle, a decade after the global economic crisis first hit. As InvestigateEurope has recently reported, labour law reform, undertaken at the behest of the ‘Troika’ of the EU, IMF and World Bank, and corporate lobby groups such as the Foreign Investors Council and American Chamber of Commerce, has left working Romanians on poverty wages.

In the DG ECFIN workshop in November 2015, there was extended discussion about SOEs in Romania. A presentation by a World Bank official refers to “reignite the IPO [Initial Public Offering of shares ie a sell-off] and privatization agenda” as a “key factor going forward”.

The online version of the workshop programme lists a staffer from Franklin Templeton Investments as one of the speakers to discuss Poland and Romania (although in the end this speaker did not participate). US-based Franklin Templeton is one of the largest investment funds in the world and it manages Fondul Proprietatea, which was originally set up in 2005 as a fund to compensate Romanians whose properties had been seized during the Communist regime. According to a press release, Fondul Proprietatea “invests in Romania’s most profitable and largest listed companies such as OMV Petrom (the largest oil producer in Romania), Romgaz (the largest gas producer in the country) and in large unlisted state-controlled infrastructure assets such as Bucharest Airport and the port of Constanta.”

Since April 2013, the board of Fondul Proprietatea has included Mark Gitenstein, the US Ambassador to Bucharest from 2009 to 2012. Simultaneously, Gitenstein is also a special counsel to major US lobbying law firm Mayer Brown. According to his Mayer Brown profile, as Ambassador Gitenstein he “encouraged greater private sector involvement in state-owned enterprises (SOEs), including the introduction of a corporate governance code for SOEs”. At the time of his appointment to Mayer Brown, Gitenstein himself said: “Commercial opportunities abound in Romania and throughout Central and Eastern Europe, and my experience and contacts in the region can help clients capitalize on them.”

DG ECFIN staff met with Franklin Templeton three times in 2015 to discuss Romanian SOEs in the context of Romania’s post-crash bailout programme. We don’t know who DG ECFIN met from Franklin Templeton nor what was said as no minutes of these meetings were made. While Franklin Templeton surely has insights into the Romanian economy and the economic performance of SOEs, it is likely that those insights are from a narrow corporate perspective. Afterall, Franklin Templeton is a lobbying organisation. It is listed in the EU’s lobby transparency register as holding three European Parliament access passes and in 2015-16, it declared having spent €100,000 – €199,999 on lobbying. Should DG ECFIN really have met this investment fund three times in less than six months?

Next steps for KPMG study

The KPMG / Bocconi project will be completed by the end of November 2017 and the Commission has told Corporate Europe Observatory that the final report will be made public. Meanwhile, in 2017, at least five countries had European Semester final recommendations involving SOEs, including some which included divestment or privatisation: Croatia, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, and Cyprus.

In September 2017, MEP Molly Scott Cato asked a written question to the Commission which illustrates some of the concerns which are raised by DG ECFIN’s contract, but at the time of writing, it had not been answered.

Corporate Europe Observatory’s concerns include:

-

How can a commissioned study to “provide an overview of assets (including state-owned enterprises) owned by the public sector in the 28 member states and [to] encourage the adoption of best practices regarding the management (including the restructuring and/or privatisation)…” be compatible with TFEU 345 which says that “The Treaties shall in no way prejudice the rules in Member States governing the system of property ownership”?

-

Can European Semester recommendations which promote privatisation really be compatible with the Treaty’s neutrality on property ownership?

-

Should there not be an equivalent study which maps the assets of major private sector companies across EU member states? There could be many benefits of this kind of study, not least in the context of corporate tax avoidance, where public authorities should be reclaiming unpaid taxes.

Be the first to comment