It is now impossible to address the climate emergency without making equity central to the solution.

Dan Calverley is an independent researcher on climate change and mitigation

Kevin Anderson is professor of energy and climate change at the Universities of Manchester (UK), Uppsala (Sweden) and Bergen (Norway)

Cross-posted from Climate Uncensored

In 2015 the countries of the world came together in Paris and agreed to cut emissions to hold global warming to “well below 2°C” and ideally to not exceed 1.5°C [1]. The Paris Agreement stipulated that wealthy countries with greater historical responsibility for causing climate change should make bigger cuts in emissions than poorer countries that haven’t emitted as much. In the Paris Agreement this is enshrined as the long-standing principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’ – ‘CBDR-RC’ for short. An even shorter term for this principle is ‘equity’, or simply fairness.

For a ‘good chance’ of holding warming to below 2°C, we are now limited to emitting a little under 700 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (about seventeen years’ worth of emissions at the current global rate). This global budget is for all emissions from energy out to the end of the century and beyond [2]. However, while the Paris Agreement emphasises the importance of equity in dividing the global carbon budget among individual countries, it doesn’t tell us exactly how to divide it.

We get the budget from science, specifically from our understanding of how the climate and average temperatures respond over time to inputs of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. But how we share the carbon budget between countries is not usually thought to be part of science. Indeed, when politicians and scientists talk about climate change, they often focus on the science part and treat equity (or fairness) as a sort of ‘nice to have’ element. How to share the budget is normally thought to be the realm of politics and morality, rather than science. So it’s for all of us to decide what’s fair and in various ways engage with our elected officials, who then negotiate a consensus at international climate meetings and conferences.

But although equity is certainly about moral and political judgements, it is still shaped by real-world, physical, constraints. Perhaps foremost among these important practical constraints is the varying rate at which different countries are capable of cutting their emissions while providing for the energy and food needs of their citizens. Capability here is essentially another way of saying how wealthy a country is – can it raise finance to produce or buy the necessary materials and labour to decarbonise its infrastructure?

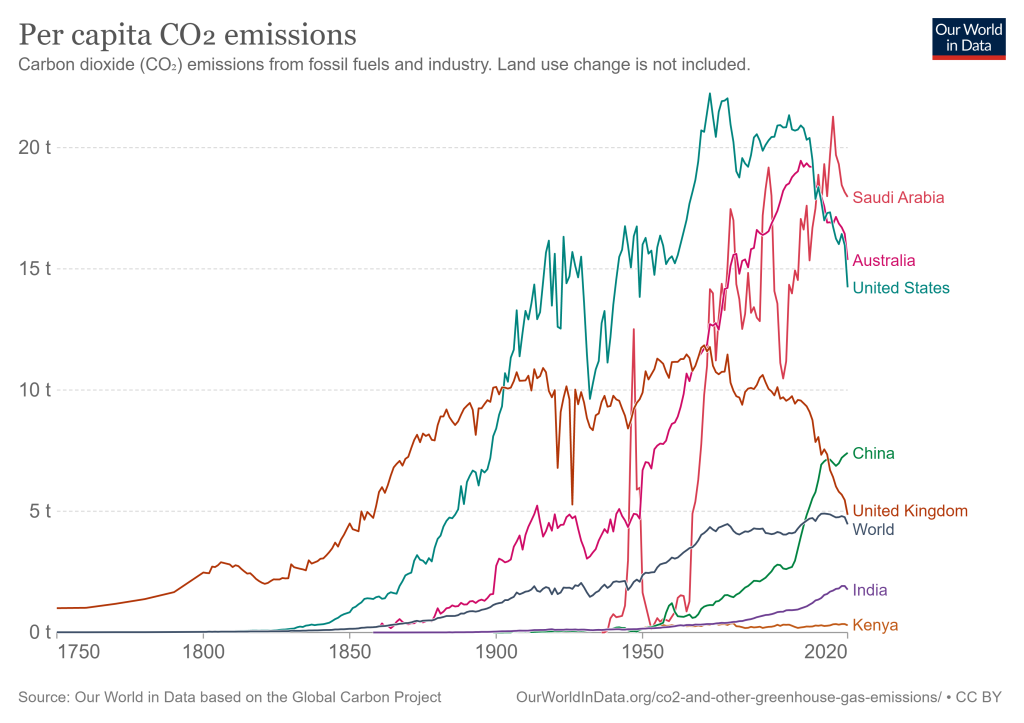

A second constraint is how much a country emits per person, and from what sources. Putting it simply, countries with relatively low emissions per person will not be able to cut their emissions as much or as easily as countries with higher emissions per person. As we mention in our companion video to this blog , countries have very different levels of emissions per person – see chart below and further information at https://ourworldindata.org/per-capita-co2.

A third crucial constraint is that all the emissions from all countries must fit within the overall global carbon budget. It’s no good each country claiming to ‘do its best’ if global emissions still exceed the budget for 2°C (or 1.5°C) when we add up all the cuts.

It’s important to keep these constraints in mind when we consider the mechanism by which the Paris Agreement requires countries to say how much they will reduce their emissions by. Since Paris, countries make ‘pledges’ to reduce their emissions, known as Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs for short. Countries have to pledge cuts that reflect their ‘highest possible ambition’, but this level is left for individual countries to define – and indeed many countries have interpreted this as making reductions in the carbon intensity of their economies, rather than absolute cuts in emissions. Moreover, most NDC pledges cover only the period to 2030; countries may outline future cuts beyond then if they so choose, but few have done so. In developing their NDC, countries are not required to consider others’ NDCs or how they collectively affect the remaining global budget.

So, we’re now in a situation where all the NDC pledges of all the countries in the world add up to a carbon budget more in line with 3 to 4°C of warming than 1.5 to 2°C [3 ]. One of the reasons we’re in this mess has to do with international equity. The NDC pledges of wealthy countries do not take account of the need for poorer countries to emit more in the short term to meet their basic welfare needs, before beginning their own rapid cuts.

This practical side of equity is rarely discussed, and it’s a problem because it will literally determine whether we succeed or fail on climate change. If rich countries don’t cut their emissions faster to give poor countries the necessary breathing space, then either poor countries must sacrifice their basic needs and quality of life (and the lives of many of their citizens), or we all fail to avert the dire consequences of increasing impacts of higher levels of climate change. Without addressing equity, we cannot solve climate change.

Another reason why the current NDC pledges add up to more than the remaining global budget has to do with intergenerational equity – that is, fairness between generations. At present, many countries plan to continue emitting at relatively high levels because they assume that future generations will have the technology to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it away safely forever.

Scientists and engineers are currently researching a variety of techniques to capture and store atmospheric carbon dioxide – what’s known as carbon dioxide removal, CDR for short. But there are huge risks in assuming that we’ll find ways to scale up these still experimental techniques and deliver the enormous quantities of so-called ‘negative’ emissions that the wealthy countries are relying on. In effect, we are counting on future generations to work out how to clean up our emissions or to face the impacts of yet more climate change. This is a devastating and inequitable legacy to hand to our children and our grandchildren. [We are currently working on a short, animated film that delves further into the concept of negative emissions].

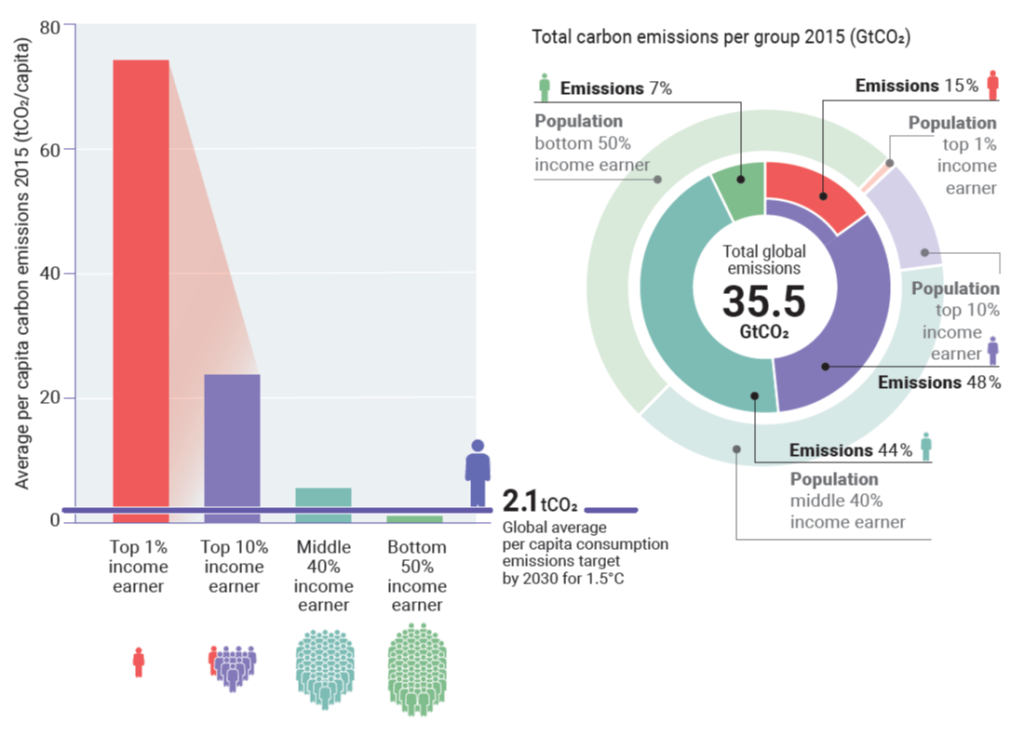

Finally, a third aspect of equity relates to who needs to cut emissions within countries. The numbers here are stark. Almost half of all carbon dioxide comes from the wealthiest 10% of people worldwide (roughly 1 in 3 citizens of wealthy countries fall into this category). And the wealthiest 1% globally (the super-emitters) have lifestyles that emit twice as much carbon dioxide as the entire bottom half of the world’s population.

Given these huge differences in emissions across different income groups, it’s obvious that curbing emissions from high-emitting, wealthy people is far more effective and equitable than trying to cut the already low emissions from poorer citizens. Policies that aim to reduce the emissions of low emitters are not only inequitable, they simply fail to target the bulk of emissions. Again, without equity, we fail to address the problem of the climate emergency.

In summary, why is fairness key to staying within the 1.5 to 2°C global carbon budget?

- First: For poorer nations to raise their level of wellbeing closer to the global average [4], fairness demands immediate and deep cuts in emissions by richer nations.

- Second: If we are not to hand our children a potentially impossible burden for removing our carbon from the atmosphere, fairness demands immediate and deep cuts by the people emitting now.

- And third: to target the vast bulk of carbon being emitted today, fairness (and effectiveness) demands that the highest emitting, wealthiest citizens should make the biggest cuts.

Be the first to comment