Rather than promising growth tomorrow, policy-makers should give more to younger generations today

is Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography, University of Oxford

Cross-posted from Danny Dorling´s blog

Slowing GDP growth

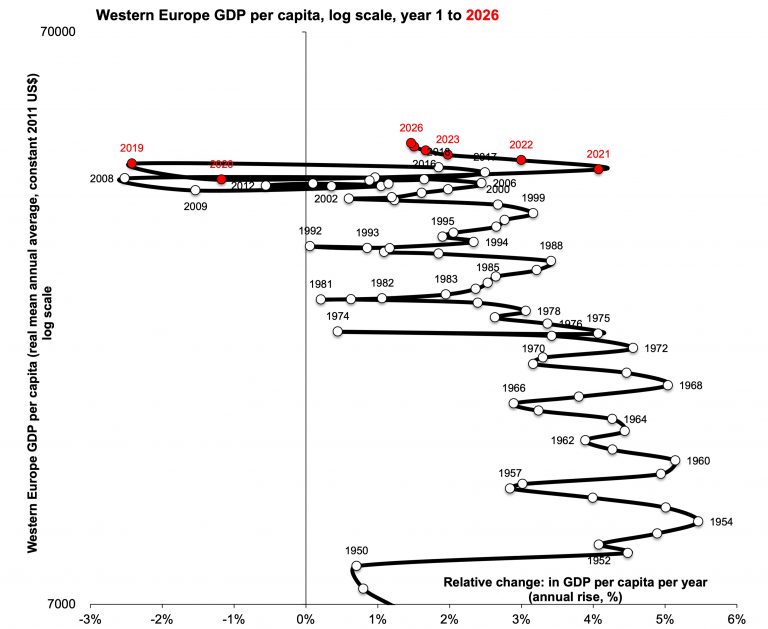

We tend to assume that there will always be an economic recovery after a slump. However, in Western Europe the rate of economic growth has been slowing down gradually each year since at least 1954. The graph here shows that trend and includes estimates and projections made by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the years 2019 to 2026 in red.

These projections may be a little optimistic, suggesting for 2021 the strongest economic recovery in a year as measured since the 1970s. However, by 2026 the IMF projections are back on the slowing track they have been on since 1954. Draw a line between the 1954 and 2026 points in the graph to see the direction of travel.

Trend in Western Europe GDP estimated, and projected by the IMF up to the year 2026

Sources of data used to draw the graph, with assistance from Qiujie Shi: Maddison Project Database, version 2018. Jutta Bolt, Robert Inklaar, Herman de Jong and Jan Luiten van Zanden (2018); ; 17 July 2019 2017-2026 data are added using change from 2016 according to IMF estimate of GDP per capita, PPP (constant 2017 international dollars). Data after 2019 are the projections of the IMF.

This graph of Western’s Europe’s GDP begins with a slump in the years immediately after World War Two, and the recovery from that in the early 1950s. Some people imagine that a similar recovery might be possible now, but that is unlikely because we are in a very different context. Europe is not now a shattered continent in which the buildings, homes, and infrastructure urgently needs to be rebuilt, as it was in the early 1950s.

In particular, Western Europe has recently suffered two enormous economic shocks, that of 2008 and that of 2019; but these were shocks that do not result in rebuilding needs, but instead resulted in banks becoming financially unstable and millions of people being furloughed and paid to do nothing. Incidentally, there were large global influenza pandemics in 1957 and from 1968-1970 which may possibly be associated with very slight drops in GDP in the past. All across Europe we behaved very differently when a pandemic struck again in early 2020.

We have hammered the young

All young people in Western Europe born from 1990 onwards have grown up to experience economic turmoil and crashes far in excess of the oil shocks of the 1970s or the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s.

It was partly in reaction to the crash of 2008 that from 2012 onwards (outside of Scotland) older adults decided that the half of young people who go to university should be made to pay enormous fees and 90% of them get into huge debt (parents paid the fees of around 10%). It was because older adults did not trust the young that they “sanctioned” so many of them in 2014 with the most enormous fines ever handed out in British history. Two years on and in 2016 the old (it was mostly the old) voted against the wishes of the young for the UK to leave the EU. I could go on; but hopefully do not need to, as the point has been made – we have hammered the young.

“Just wait,” they say

What older people may now tell younger adults and children is that they need not worry. They say that an economic recovery is coming. They say that there will be good jobs for all in the future; that your student loan debts will not worry you as your future income rises; that somehow homes will become affordable; that being sanctioned so much and having to take so many poorly paid jobs will just become a memory. “Just wait”, they say.

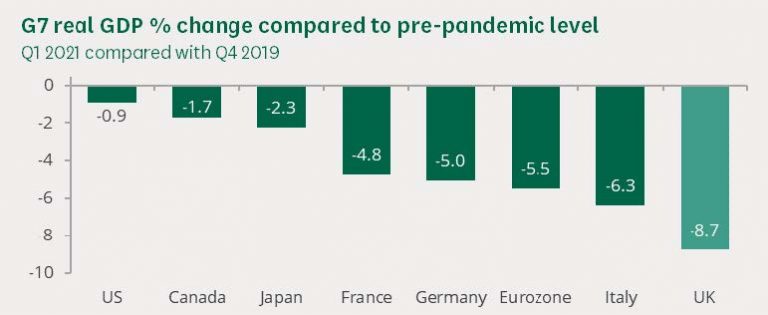

However, waiting would be foolhardy, especially in Britain. A recent House of Commons report of June 2021 has shown that when looking across all of Western Europe it was the UK that has been especially badly hit in the most recent crisis. That does not mean we will have some great “recovery” next.

Comparisons of GDP change in C7 countries

Source: House of Commons Library, Research Briefing: GDP – International Comparisons: Key Economic Indicators, published Friday, 04 June, 2021,

Note: GDP figures are not exactly compatible and so there would be a slight difference is exactly comparable measures were available; but these are the most comparable estimates the House of Commons Library has.

Do not trust future growth

So, what should policies be for the young in Britain? What can be done for those who have seen their interests so badly damaged over the course of the last ten years and whose schooling and employment was deemed to not be a great priority during the pandemic? My answer is that no policy that relies on a promise of future growth should be trusted.

The rate of growth has been slowing for almost 70 years, worldwide but especially in Europe and even more slowly in the UK. Environmentally this may well be a good thing; but it is part of the reason why the young have been penalised.

Unequal society

Within the last forty years the UK has become the most economically unequal state in all of Western Europe by a long margin. The affluent (who were mostly old) wanted to maintain and improve their own living standards, and when there was not enough to go round they did this at the expense of the poor and the young. Future polices should ensure better sharing of what we have, rather than promises to increase the size of the cake.

Even if that were environmentally desirable, which it is not, increasing the size of the cake greatly now is impossible. On 15 January 2015 George Osborne (then the Chancellor of the Exchequer) promised to make the UK the highest GDP/capita large country in the world by 2030. He said this would happen if only people would go along with his economic plan. In hindsight that was an even more ridiculous statement than it appeared to be at the time.

Share today

“Jam tomorrow” has always been the promise made to the young by those who are old and devious. “Share today” should be the reply from here on. Share out the educational debts; share out the costs of supporting yourself when out of work and when in low paid work; share (rather than hoard) the housing; share properly; and share now. Plan to share at the rate that the average Western European state shares its resources. Treat the young at least as well as is normal now in the rest of Western Europe. The alternative is a miserable future for most young people in Britain.

Be the first to comment