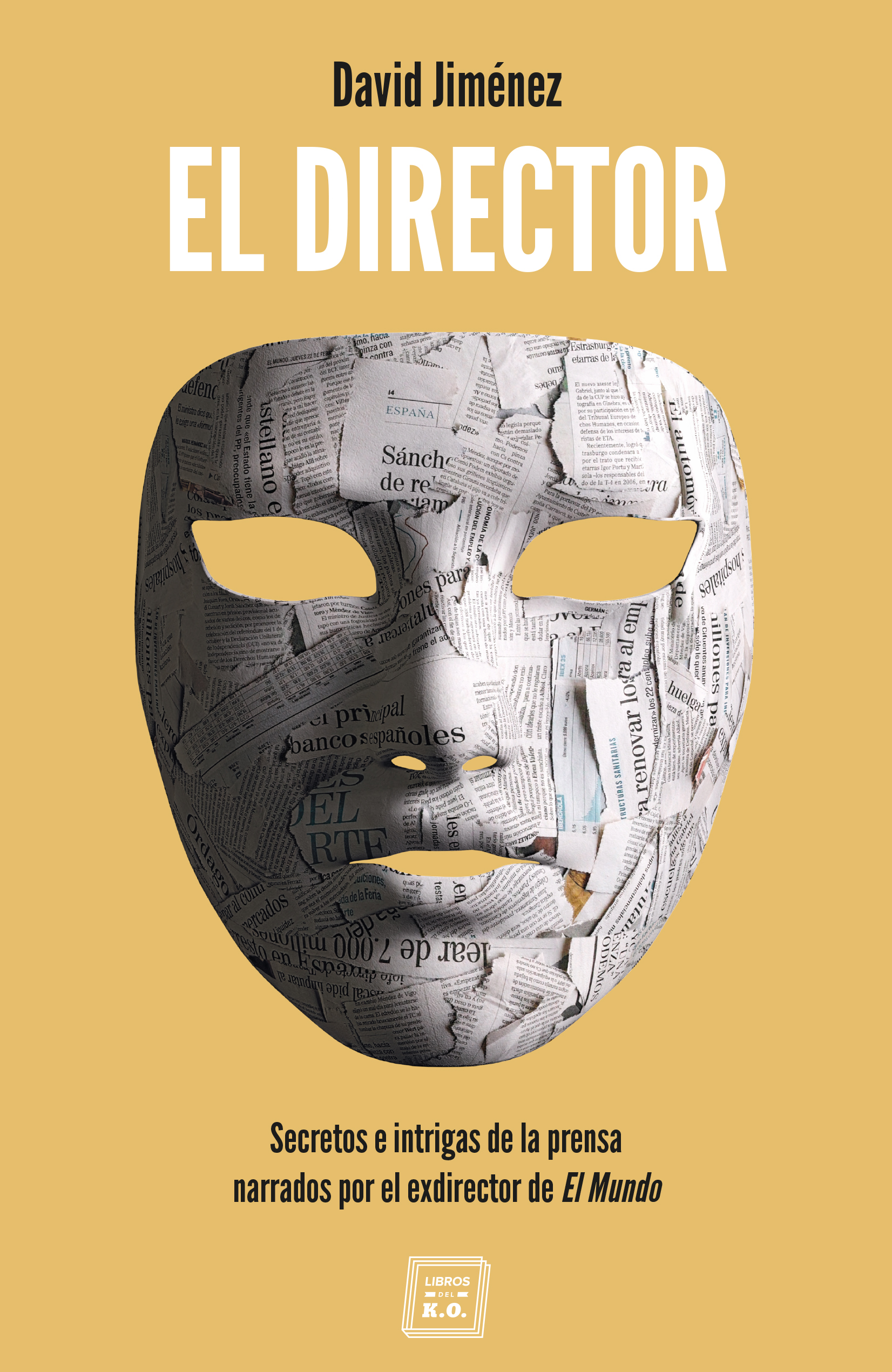

After 18 years as a war reporter and correspondent, David Jiménez was appointed editor-in-chief of El Mundo, one of Spain’s biggest dailies, at the end of his Nieman fellowship at Harvard in 2015. What seemed like an exciting challenge soon became a battle to defend the newspaper’s independence against a political and economic establishment determined to bring it down. “El Director” (“The Editor”), his tell-all book about his year at the helm of El Mundo, has rocked the political, business, and media worlds in Spain.

Published in Spain in April by Libros Del Ko, the book has opened a debate about Spanish media’s ties to powerful interests and became a campaign issue in the most recent general election. But it has been in the country’s newsrooms where it has provoked the biggest stir, thanks to revelations of corruption in the press corps that have broken a decades-long code of silence. “We journalists love to tell a great story,” Jiménez writes in“El Director.” “Just not ours.” In the book, nicknames are used for people who still work at El Mundo, including the executive called the “Cardinal.”

This adapted excerpt has been translated from Spanish by Dick Cluster

Cross-posted from Niemann Reports

And he walked out with two TVs.

Free meals in the best restaurants, cars lent out for indefinite periods, and bank loans at interest rates unimaginable to other mortals were the order of the day. A former board member of Banco Popular told me that the company’s policy was to “keep the financial reporters happy” with mortgages at below-market rates to assure friendly coverage. The firm later went belly-up, despite having maintained an image as the best-managed bank in the country for decades.

It was a system in which the staff made off with the bulk of the booty, but there was always something for the grunts too.

“Free trip to Tanzania!” someone would call out in the newsroom. “Who wants it?”

“Dinner at the Ritz!”

“Press conference for a luxury watch brand. One could be yours.”

There came a time when someone had to remind the editors that such trips counted as vacations, not work time, even if the travelers filed stories dictated by the tourism offices when they got home.

Although the economic crisis put an end to the open bar, the party still rolled on for the aristocrats of the newsroom. We journalists were so convinced of our exceptionalism, of being members of a privileged caste that deserved preferential treatment, that one of the country’s most celebrated journalists, who used to work for El Mundo, called the Madrid city government to send firefighters to her house because she’d locked her keys inside. When they suggested she call a locksmith instead, her surprise befitted a member of a fraternity who had lost all contact with reality:

“But that would cost me a fortune!” she complained.

That world of privileges had begun before I left for Asia as a foreign correspondent, but during my absence it had mushroomed. “Bonuses” issued under the table to reporters and announcers were now the order of the day, doled out by public relations firms, soccer teams, political parties, and big companies. Buying a journalist was impossible in Spain, but as the Afghan saying about corruption has it, “Renting, on the other hand…”

In the midst of the recession, and with newsrooms hit by thousands of layoffs, an appearance on a political talk show was enough to “bag” a journalist. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s administration insisted on the firing of journalists who made it uncomfortable. They used government-funded advertising to punish the disobedient ones, and they controlled who could appear on radio and television. This control reached such levels that the two main factions within the executive branch, led respectively by Vice President Soraya Saénz de Santamaría and Party Secretary María Dolores Cospedal, battled over who could place more of their allies on the talk shows for the purpose of mutual attacks, showing that in politics, friendly fire is always the most deadly. This was a war in which journalists were humiliated through messages telling them what slogans to repeat, in which blind loyalty was demanded, and careers were ruined or nurtured on a whim.

One of those in charge of safeguarding the connection between the powers-that-be and the media was the Secretary of State for Communication, Carmen Martínez Castro, known as “the bulldog of Moncloa” for the diatribes she directed at journalists and media executives. Her messages were legendary among journalists, and it didn’t take me long to receive my first, which was a complaint about our cartoonists Gallego & Rey making fun of Prime Minister Rajoy’s connection with the corruption of his party.

“What current relevance, what allusion to anything newsworthy, what trace of humor is there in this cartoon?” asked the Secretary of State for Communication in a text containing spelling errors. “I see only a desire to denigrate the president, without the slightest justification in his behavior or in current events.”

When I quoted this message to my staff, they told me it was Castro light. Normally she would include personal insults, but apparently she didn’t feel sure of me yet, and so she was treating me with “affection.” Eighteen years had passed since I’d last practiced journalism in my country, but I needed only a few days to discover that something fundamental had changed in my absence. The powerful had ceased to fear the press; now it was the press that feared the powerful.

The “Accords,” as the pacts negotiated by the press with large corporations were known, had saved the traditional daily papers during the Great Recession. These were a system of favors in which, in return for the papers receiving more advertising money than they deserved in terms of circulation or market impact numbers, they offered friendly coverage, whitewashed the images of the heads of the big corporations, and exempted those firms and figures from bad news. No one had to spell out the fine print of the Accords for me, because I had experienced their reach even as a correspondent in far-off Asia, after the 2013 building collapse in Bangladesh in which more than a thousand textile factory workers died.

In the midst of preparations to go to Dhaka, I made some calls and learned through a contact that El Corte Inglés was one of the retail chains that manufactured clothing in the Rana Plaza, the building that had collapsed. I filed my story late at night, and in the morning I got an email from the International desk that began, “I know you’re going to throw a fit…”

All references to El Corte Inglés, one of the country’s largest advertisers, which had kept up its investment through the worst years of the crisis, had been cut from the article. I couldn’t see how the good name of a corporation was more important than news of a tragedy that cost the lives of so many people. I called my bosses—indeed, I threw a fit—and told them I was canceling my trip to Bangladesh. I wouldn’t write any more about the event unless I had a written guarantee that my pieces would not be censored. For the next two days I was in constant conflict with the staff, who kept demanding I go to Dhaka. The paper had to continue its coverage with wire service dispatches.

The exchange of favors between the press and the corporations was so deeply rooted for so long, that nobody even had to pick up the phone to demand that dues be paid. The newsrooms had internalized the fact that the companies like Telefónica, Banco Santander, or El Corte Inglés were untouchable. Now that I found myself on the other side of the fence, I wondered whether I could maintain my professional ethics with the same determination as when I’d been a mere reporter without responsibility for the overall condition of the paper, which was going through the worst financial crisis of its history and could not afford to lose the advertising of its biggest clients.

At first I chose to maintain a certain distance from the presidents of the biggest companies, so as to stave off moral dilemmas. It wasn’t a matter of avoiding all contact, just the kind of close relationships that would compromise our coverage of the leading firms. I had no hard-and-fast boundary, but it seemed evident that going to the weddings of daughters of top executives, taking the sun on the decks of their yachts, or letting them buy me luxury trips would be crossing the line. Soon after I arrived, I rejected an invitation from CaixaBank for myself and a companion to go to a private Sting concert with all expenses paid, including a six-star hotel, first-class air tickets, and chauffeuring from my door. While reading the details of the excursion, surprised that a bank on which we reported on a near-daily basis would expect me to accept the proposal, I came to the list of the previous year’s invitees. No one was missing: newspaper editors-in-chief, radio and TV announcers, executives of press groups, and famous journalists.

My diplomatic rejections of boxes, private events, and travels were interpreted as gestures of disdain. The “Cardinal” reproached me, telling me that his friends at IBEX-listed companies were complaining about what they considered my arrogant attitude. The top executive of our company, who had hired me a few months before, had survived in his job thanks to the protection of some of them. He had emerged victorious from all the crises at the paper, won all the internal battles and eliminated all his rivals, real and imaginary, to stay ahead among waves of layoffs, threats of bankruptcy, and political sieges. And he had done all this without wrinkling his suit, without a bad word or gesture toward anyone, maneuvering and getting rid of his adversaries with the discreet opacity of a cardinal, always finding a way out of the labyrinth of intrigue in which others got lost. The joke that circulated in the newsroom was that, in the event of a nuclear apocalypse, the next day our front page headline would read: “Only the Cockroaches and The Cardinal Survived.”

“They say they’ve got nobody to talk to at El Mundo,” said the “Cardinal” of his friends in high places.

A few days later, he asked me to accompany him to an appointment with Francisco González, the all-powerful president of the BBVA bank. González’s office, on the top floor of the bank’s then-headquarters on the Paseo de la Castellana, was big enough to hold an entire newsroom. The “Cardinal” began to talk about the difficulties though which the newspaper industry was passing and what a hard time the company was having balancing its books for the year. And, as naturally as someone might request a second teaspoonful of sugar for his coffee, he let drop the possibility that a goodly sum could be added to the Accords we had with the bank. González said he’d see to it, without any further discussion. The bank, like other IBEX companies, had a fund set aside for buying journalistic favors, helping to start papers staffed by sympathetic reporters, and rewarding those who helped improve the image of its president. I left the meeting with the feeling that I had been brought along as a disciple, to teach me how “these things” were done.

I began to suffer from the nuisance of frequent phone calls from the country’s economic elite, because once they made your acquaintance, you could be sure that they would call. At first, their requests seemed quite innocent. Borja Prado, the president of the energy multinational Endesa, whom I had been told was key to my survival because he was “the Italians’ man in Spain,” called to request inclusion in Vox Populi, the feature on the Opinion pages in which we published thumbnail photos of leading figures with an arrow pointing up or down and a positive or negative commentary on something they had done. I had a hard time believing that someone who made an astronomical salary and ran a company with thousands of employees would care at all about our tiny feature, but it wasn’t my job to plumb the imponderable mysteries of the human ego, nor did it trouble me much to satisfy his. One column-inch in the paper was surely not committing me to anything. Pablo Isla, president of the Zara clothing empire, once asked us to treat an item about his son Santi with more discretion; Santi had a rock band and a sense of humor that led him to name his previous group Sin Blanca (“Dead Broke”). “To preserve the family’s privacy,” Isla said. That seemed okay to me, because the item had run all morning on the web site, and it wasn’t of any importance. I knew that sooner or later I’d have to deal with more compromising requests and more important battles.

The biggest of them did not take long to arrive. The most powerful businessman in Spain, César Alierta, had built a formidable network of power and influence using Telefónica, the seventh largest telecom company in the world, as his personal patio. You could walk through the corridors of the corporation´s headquarters and see the office doors bearing the names of politicians, relatives of the elite, and royal family members who had been given an office by its president. He had appointed the king’s brother-in-law, Iñaki Urdangarin, to a high post in Washington about the time he was involved in a corruption case.

One of our business correspondents came to me with sensitive information regarding Alierta’s partnership with Rodrigo Rato, the former managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) who would end up in jail for corruption. Alierta had a stake in a hotel in Berlin that Spanish prosecutors suspected had been used by Rato for money laundering and tax evasion.

I intended to run the story.

One hour after our reporter left my office, I received a call from the “Cardinal.” “This Alierta thing … we can’t run it, not this one,” he said.

I was surprised that he was aware of a story that I had not mentioned to him. It was the first of many clues that would lead me to conclude that he maintained a parallel relationship with some of my journalists, skipping over the editor-in-chief who ignored his commands to negotiate the treatment of some problematic pieces directly with them.

“This is very, very serious,” he continued. “I have spoken with Alierta and he asks us not to run it. Everything has been done legally. He does not understand this persecution.”

I insisted it was a relevant story and told him we would go ahead with it.

The “Cardinal” lost his composure for once.

“You do not understand it! You can’t do journalism if there is not a newspaper to do it. We are about to sign the sponsorship agreement with them.”

“Are you telling me they’re threatening not to sign it?” I asked.

“What I am telling you is that we live on favors. That’s the reality. We can’t go against the friends who help us. This is not a foreign bureau, you have responsibilities. With the company. With your companions. With the newspaper.”

The deadline for publication was approaching and I was determined to go ahead.

The “Cardinal” came down to my office and made one last attempt to stop the publication, recovering the paternal tone he used other times. He walked around the room, as if he was about to say something he shouldn’t. The door was slightly ajar, giving a glimpse of the newsroom. “Think of them,” he said. “These are decisions that cost jobs.”

It was a low blow.

By linking my decision to the future of my colleagues, the “Cardinal” subjected me to an emotional blackmail that he thought could work. Was I not being selfish if I chose to publish, regardless of the consequences it could have for my journalists, some of them longtime friends? If I chose not to, was not I also betraying them, by failing to defend the integrity of the newspaper? Was there any way to do both, to fulfill my promise to be loyal to the newsroom and to the readers, and to not put the paper’s economic survival at risk?

The “Cardinal” departed, leaving all those questions in the air, and for a moment I missed the lightness of infantry journalism, when my main concern was to get a visa to enter a country about to fall apart, not to save my reporters’ mortgages.

We published the article in our Sunday edition, and soon after, a colleague at one of our competitors told me that from now on I should watch my back. Not only had I published something negative about one of the Ibex’s Untouchables, disavowing my boss before his inner circle of power, but I had broken the “Accords” that governed the relations between the economic, political, and media triumvirate that controlled the levers of power in Spain.

Be the first to comment