In part two of Michael Robert´s analysis of the euro currency, he considers the impact of the global slump of 2008-9 and the ensuing euro debt crisis on prospects for the euro.

For part 1 see here

Michael Roberts – Economist in the City of London and prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael Roberts Blog

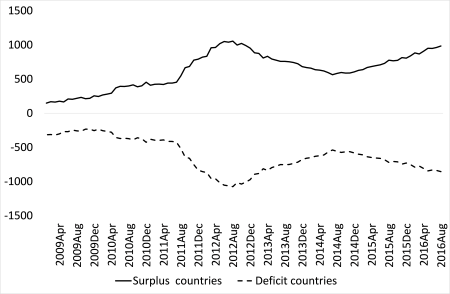

The global slump dramatically increased the divergent forces within the euro. The fragmentation of capital flows between the strong and weak Eurozone states exploded. The capitalist sectors of the richer economies like Germany stopped lending directly to the weaker capitalist sectors in Greece and Slovenia, etc. As a result, in order to maintain a single currency for all, the official monetary authority, the ECB, and the national central banks had to provide the loans instead. The Eurosystem’s ‘Target 2’ settlement figures between the national central banks revealed this huge divergence within the Eurozone.

The imposition of austerity measures by the Franco-German EU leadership on the ‘distressed’ countries during the crisis was the result of the ‘halfway house’ of euro criteria. There was no full fiscal union (tax harmonisation and automatic transfer of revenues to those national economies with deficits); there was no automatic injection of credit to cover capital flight and trade deficits (federal banking); and there was no banking union with EU-wide regulation and weak banks could be helped by stronger ones. These conditions were the norm in full federal unions like the United States or the United Kingdom. Instead, in the Eurozone, everything had to be agreed by tortuous negotiation among the Euro states.

In this halfway house, Franco-German capital was not prepared to pay for the ‘excesses’ of the weaker capitalist states. Thus any bailout programmes were combined with ‘austerity’ for those countries to make the people of the distressed states pay with cuts in welfare, pensions and real wages, and to repay (virtually in full) their creditors (the banks of France and Germany and the UK). The debt owed to the Franco-German banks was transferred to the EU state institutions and the IMF – in the case of Greece, probably in perpetuity.

The ECB, the EU Commission, and the governments of the Eurozone proclaimed that austerity was the only way Europe was to escape from the Great Recession. Austerity in the public spending could force convergence on fiscal accounts too (123118-euroeconomicanalyst-weekly). But the real aim of austerity was to achieve a sharp fall in real wages and cuts in corporate taxes and thus raise the share of profit and profitability of capital. Indeed, after a decade of austerity, very little progress has been achieved in meeting the fiscal targets (particularly in reducing debt ratios); and, more important, in reducing the imbalances within the Eurozone on labour costs or external trade to make the weaker more ‘competitive’.

The adjusted wage share in national income, defined here as compensation per employee as percentage of GDP at factor cost per person employed, is the cost to the capitalist economy of employing the workforce (wages and benefits) as a percentage of the new value created each year. Every capitalist economy had managed to reduce labour’s share of the new value created since 2009. Labour has been paying for this crisis everywhere.

Reduction in labour’s share of new value added 2009-15 (%)

Source: AMECO, author’s calculations

The evidence shows that those EU states that got a quicker recovery in their profitability of capital were able to recover from the euro crisis (Germany, Netherlands, Ireland etc) faster, while those that did not improve profitability stayed deep in depression (Greece).

One of the striking contributions to the fall in labour’s share of new value has been from emigration. This was one of the OCA criteria for convergence during crises and it has become an important contributor in reducing costs for the capitalist sector in the larger economies like Spain (and smaller ones like Ireland). Before the crisis, Spain was the largest recipient of immigrants to its workforce: from Latin America, Portugal, and North Africa. Now there is net emigration even with these areas.

Keynesians blame the crisis in the Eurozone on the rigidity of the single-currency area and on the strident ‘austerity’ policies of the leaders of the Eurozone, like Germany. But the euro crisis is only partly a result of the policies of austerity. Austerity was pursued, not only by the EU institutions, but also by states outside the Eurozone like the UK. Alternative Keynesian policies of fiscal stimulus and/or devaluation where applied have done little to end the slump and still made households suffer income losses. Austerity means a loss of jobs and services and nominal and real income. Keynesian policies mean a loss of real income through higher prices, a falling currency, and eventually rising interest rates.

Take Iceland, a tiny country outside the EU, let alone the Eurozone. It adopted the Keynesian policy of devaluation of the currency, a policy not available to the member states of the Eurozone. But it still meant a 40% decline in average real incomes in euro terms and nearly 20% in krona terms since 2007. Indeed, in 2015 Icelandic real wages were still below where they were in 2005, ten years earlier, while real wages in the ‘distressed’ EMU states of Ireland and Portugal have recovered.

Iceland’s rate of profit plummeted from 2005 and eventually the island’s property boom burst and along with it the banks collapsed in 2008–09. Devaluation of the currency started in 2008, but profitability up to 2012 remained well under the peak level of 2004. Profitability of capital in Iceland has now recovered but EMU distressed ‘austerity’ states, Portugal and Ireland, have actually done better and even Greek profitability has shown some revival.

Net return on capital for Iceland and Greece (2005=100)

Those arguing for exiting the euro as a solution to the Eurozone crisis hold that resorting to competitive devaluation would improve exports, production, wages, and profits. But suppose Italy exits the euro and reverts to the lira while Germany keeps the euro. Under the assumption that there are international production prices, if Italy produces with a lower technology level than that used by the German producer, there is a loss of value from the Italian to the German producer. Now if Italy devalues its currency by half, the German importer can buy twice as much of Italy’s exports but the Italian importers can still only buy the same (or less) amount of German exports. Sure, in lira terms, there is no loss of profit, but in international production value terms (euro), there is a loss. The fall in the value rate of profit is hidden by the improvement in the money (lira) rate of profit.

In sum, if Italy devalues its currency, its exporters may improve their sales and their money rate of profit. Overall employment and investments might also improve for a while. But there is a loss of value inherent in competitive devaluation. Inflation of imported consumption goods will lead to a fall in real wages. And the average rate of profit will eventually worsen with the concomitant danger of a domestic crisis in investment and production. Such are the consequences of devaluation of the currency.

The political forces that wish to break with the euro or refuse to join it have expanded electorally in many Eurozone countries. This year’s EU elections could see ‘populist’ euro-sceptic parties take 25% of the vote and hold the balance of power in some states like Austria, Poland and Italy. And yet, the euro remains popular with the majority. Indeed, sentiment has improved in 13 member states since they joined, with double-digit bumps in Austria, Finland, Germany and Portugal. Even in Italy, which has witnessed a roughly 25-point decline, around 60% of people still favour sharing a currency with their neighbours. Greeks are still 65% in favour. What this tells me is that working people in even the weaker Eurozone states reckon ‘going it alone’ outside the EU would be worse than being inside – and they are probably right.

Ultimately, whether the euro will survive in the next 20 years is a political issue. Will the people of southern Europe continue to endure more years of austerity, creating a whole ‘lost generation’ of unemployed young people, as has already happened in? Actually, the future of the euro will probably be decided not by the populists in the weaker states but by the majority view of the strategists of capital in the stronger economies. Will the governments of northern Europe eventually decide to ditch the likes of Italy, Spain, Greece etc and form a strong ‘NorEuro’ around Germany, Benelux and Poland? There is already an informal ‘Hanseatic league’ alliance being developed.

The EU leaders and strategists of capital need fast economic growth to return soon or further political explosions are likely. But as we go into 2019, the Eurozone economies are slowing down (as are the US and the UK). it may not be too long before the world economy drops into another slump. Then all bets are off on the survival of the euro.

Be the first to comment