The Labo(u)r parties in Australia and Britain have chosen to fail by following what they think is a successful strategy: not to fulfil declared social and economic objectives but to reduce government debt.

Steve Keen is an Australian economist and author. A post-Keynesian, he criticizes neoclassical economics as inconsistent, unscientific and empirically unsupported.

Cross-posted from Steve Keen’s substack Building a New Economics

UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer Photo: Serial Number 54129/Creative Commons

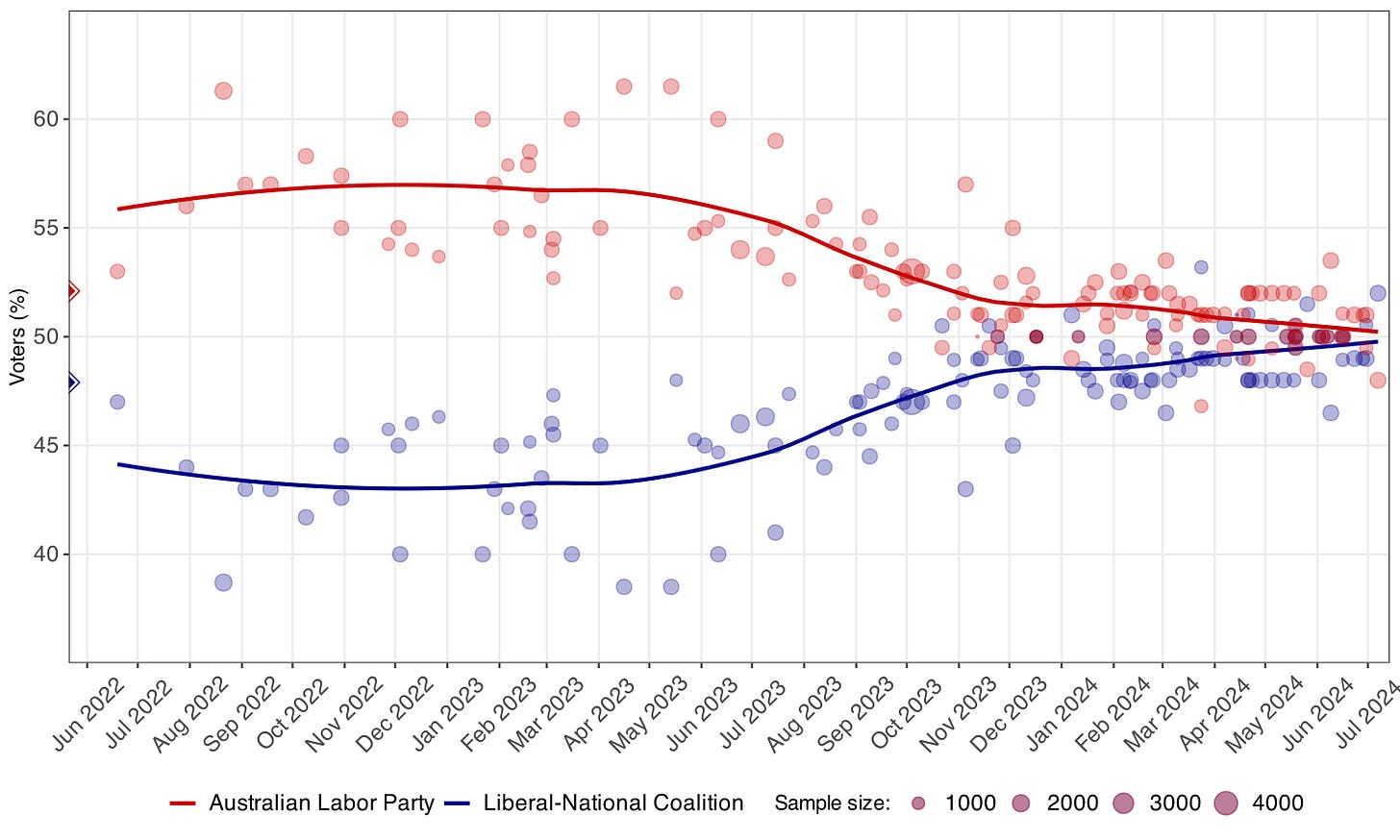

The Australian Labor Party, which was elected in May 2022 after a decade of conservative rule (by Australia’s misnamed “Liberal” Party), has destroyed its once substantial electoral lead, and now looks likely to lose the 2025 election. Its best outcome will be to hang on as a minority government, since most independents and minor parties regard the “Liberal” Party as even more obnoxious than the Albanese-led Labor Party has been while in office.

Not to be outdone, the UK’s Labour Party, elected in July 2024, has fallen from a 36% share of votes to 30% just 2 months later, while the Conservative Party has risen from 23% to 26%, and its right-wing companion Reform has risen from 15% to 19%. The UK’s bizarre first-past-the post electoral system—not so much satirized as accurately described by Monty Python’s famous Election Night Special skit—makes the outcome a crap shoot, but the odds of Labour coming out on top in 2029 are already vanishingly small.

Both Labo(u)r Parties have chosen to fail by following what they think is the successful strategy for a government: they made their first priority, not to fulfil the social and economic objectives that led voters to elect them, but to reduce government debt. In probably the most dramatic example of economic orthodoxy trumping social democracy, UK Labour Party leader Keir Starmer’s first major policy decision is to let pensioners who can’t afford heating freeze, in order to reduce the gap between government spending and taxation—which he and his Chancellor refer to as the “£22 billion black hole”—by £1.5 billion.

This fetish with reducing government spending is braindead stupid. It persists because it’s a stupidity that is taught by University economics departments, and believed by most of its students—some of whom go on to become Prime Ministers and Chancellors.

If they don’t rebel against this teaching, it comes to be the way they think the real world actually works. Whether politicians are Labour, Liberal, or Tory, whether they do just a bit of undergraduate economics in a PPE (“Philosophy, politics and economics”) degree—as Rachel Reeves did before her Masters degree—or go on to do a full PhD, the way they think as a politician is shaped by what they learnt at university.

This makes economics degrees extremely powerful, as Paul Samuelson, the author of the first post-WWII textbook, which set the mould for all its successors, fully appreciated. In the preface to a teaching guide to his textbook, he wrote that:

“I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws–or crafts its advanced treaties–if I can write its economic textbooks.” The first lick is a privileged one, impinging on the beginner’s tabula rasa at its most impressionable state. (Samuelson 1990, p. ix)

The “first lick” in one of the dominant economics textbooks today—Greg Mankiw’s Macroeconomics {Mankiw, 2016 #6107}—is a model which teaches students that government spending is a bad thing.

After laying out the model in the previous 30 pages, Mankiw explains that, according to the model, an increase in government spending reduces investment:

Consider first the effects of an increase in government purchases … The immediate impact is to increase the demand for goods and services… But because total output is fixed by the factors of production, the increase in government purchases must be met by a decrease in some other category of demand. Disposable income … is unchanged, so consumption … is unchanged as well. Therefore, the increase in government purchases must be met by an equal decrease in investment. (Mankiw 2016, p. 73)

Mankiw cautions that there are some “simplifying assumptions” in this model which are relaxed later—such as output being fixed. But this foundational model plants in students’ heads the idea that government spending—say, on giving pensioners additional money for heating during winter—will come at the expense of the future growth of the economy.

The removal of some assumptions in subsequent models doesn’t change the underlying proposition: government spending in excess of taxation harms the economy. This belief, etched on “the beginner’s tabula rasa at its most impressionable state”, as Samuelson put it, is why Starmer and Reeves think that letting pensioners freeze will be good for the economy.

In reality, it won’t—not merely because the simplifying assumptions of this model are wrong, but because its fundamental assumptions about what government spending does, how it is financed, and the impact of government spending on private investment, are also wrong.

I’ll explain why in subsequent posts.

Due to the Israeli war crimes in Gaza we have increased our coverage from five to six days a week. We do not have the funds to do this, but felt that it was the only right thing to do. So if you have not already donated for this year, please do so now. To donate please go HERE.

Be the first to comment