Despite the Brexit discussion in the UK other topics are inexorably moving forward. In this piece Stewart Lansley provides new thoughts concerning Universal Basic Income.

Stewart Lansley is a visiting fellow at London’s City University and co-editor with Amy Downes of It’s Basic Income: The Global Debate, Policy Press, 2018. It was reviewed in BRAVE NEW EUROPE – Read here

After the War, the Beveridge plan had an ambitious goal: to provide an income floor based on a mix of national insurance, family allowances, full employment and a fall-back safety net of national assistance. Together these were meant to ensure that everybody would be guaranteed a minimum income if at subsistence level. Beveridge always intended that national assistance would play no more than a residual and transitory role, and would soon wither away.

In the event, the proposed income floor was inadequate and always patchy. It became more so as the economy faltered from the 1960s, Britain became an increasingly low wage economy and the social security system was gradually converted into a highly punitive and controlling mechanism for those of working age. Today’s income support system is full of holes, is far removed from Beveridge’s key principle of universality and has become an increasingly means-tested, targeted system. As a result, it is weak at delivering on its primary goals, to alleviate and prevent poverty in a world of increasing uncertainty and volatility.

There are now growing calls for reform. But what form should it take? Returning to the pre-2010 position by restoring former benefit levels is not the answer. This approach would merely retain a system still heavily dependent on means-testing, still highly conditional and still lacking a guaranteed income floor. Another option would be to strengthen the social insurance system, but as Ruth Lister has said, there is a “question mark over how far social insurance can provide adequate even quasi ‘universality of protection’ for many in today’s – and even more so tomorrow’s – insecure labour market.”

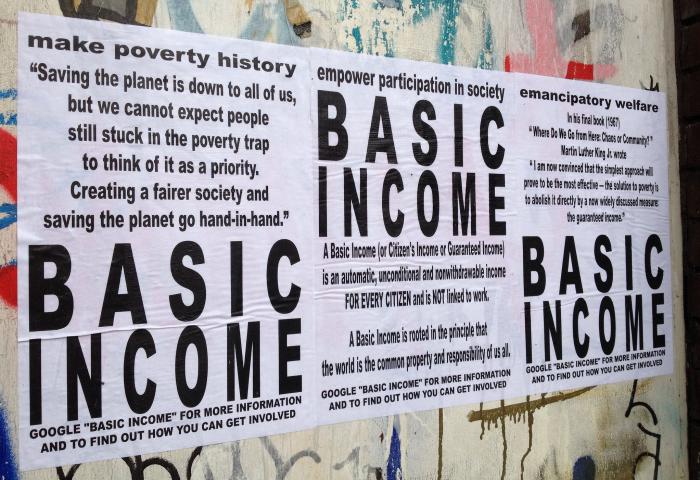

It is therefore time to think beyond yesterday’s models of social insurance and means-testing, in favour of a radical upgrade of the Beveridge model. What is needed is a new social contract fit for the 21st century that finally delivers on the promise of 1948. This approach should be founded on four key principles. First, the construction of an initial income floor through the provision of a guaranteed, basic income for all citizens, as of right. Secondly, greater universalism, with a lowering of the role of means-testing. Thirdly, an end to today’s ‘hostile environment’ towards the poor. Finally, the income floor should be gradually raised over time by tapping into Britain’s personal wealth mountain.

The idea of a guaranteed, no questions asked basic income for all remains highly controversial. Among opponents’ claims are that the payment levels are either too small to make much difference or too generous to be affordable. There are of course many different visions of basic income, and ultimately the feasibility and impact of a scheme depends on its plumbing. A 2016 report by the progressive pressure group Compass examined two possible models, a big-bang, full-blown scheme with generous payments which would sweep away most of the existing system of social security; and a ‘partial scheme` that would pay more modest sums, and be grafted onto the existing system. This report showed that a full and generous scheme would be either too expensive, or create too many losers amongst lower income households, thus raising poverty levels. This is because the current benefits system, partly because of its reliance on means testing, is able to deliver large sums to some groups. However, the study also found that a ‘partial` scheme, one that still provided a universal and unconditional income, albeit at a moderate starting level, and that initially left much of the existing system intact, would be perfectly feasible and highly progressive.

A second report for Compass –Basic Income for All: From Desirability to Feasibility – develops that partial model. It lays out a pathway to a basic income that would proceed in a series of steps.

Step 1 to a basic income for all

As a first step, the existing personal allowance for income tax should be converted into a tax-free cash payment paid to all individuals. The personal allowance currently costs £101bn but is of no benefit to those with earnings below the tax threshold and not in work. This move alone would finance a basic payment of at least £25 per week for all adults and children (depending on how it is structured) and would be highly progressive. It would establish for the first time a firm, if modest, income floor and the principle of a guaranteed minimum income as of right, all at no additional cost to the exchequer.

Such a step could be introduced as a standalone change in the existing system. It would on its own cut poverty and inequality – and there is already some support, including from the Fabian Society, and the New Economics Foundation for such a move.

The introduction of child benefit in 1978 (which abolished child tax allowances and family allowances and converted them into a tax-free payment for all children) is a powerful precedent for converting tax allowances into flat rate cash payments. This reform – highly controversial at the time and initially opposed and delayed by the Labour cabinet – has proved one of the most important anti-poverty measures of the last 40 years.

Step 2

The next stage would be to raise this initial income floor gradually over time by increasing the rates of payment. This could also be done in steps. There is for example, a strong case for launching a young adult benefit ( parallel to child benefit ) from the age of 18-24. This would support an especially disadvantaged group at a key point in their life. Such a step would require more funding, but could be financed by adjustments to the existing tax/benefit system.

This approach to reform – through steps 1 and 2 – would be feasible, affordable and highly progressive. The second Compass report shows that a basic income floor could be introduced at modest rates of £60 for adults (up to 64), £40 for children and £175 for adults over 65 over the life of a single Parliament. This plan would pay, by example, a significant, no questions asked, £10,400 a week for a family of four, boost the incomes of the poorest households, cut poverty sharply, narrow the inequality gap, strengthen universalism while reducing dependency on means testing.

It would abolish child benefit and the state pension, but retain most of the current benefits system, including means-tested benefits. The model could be introduced at one go or phased in in steps. The illustrative scheme would cost £28bn net (met in part by some increases in taxation among higher income groups), less than the aggregate cuts to benefits since 2010. It would take the UK back to the level of social security spending in 2010, but with a much more progressive and watertight system in place.

Step 3

To put the system on a robust financial footing, a targeted citizens’ wealth fund should be created aimed at providing long term funding for raising this new income floor. Citizens’ wealth funds are a potentially powerful tool in the progressive policy armoury. They are commonly owned investment funds, transparently managed for the long term, with the returns used to raise the level of payments over time.

With such a fund, all citizens would hold a direct and equal stake in economic success, with the fund automatically capturing a growing part of the gains from economic activity and distributing the gain equally to all and across generations. The fund would take time to build and could be financed through an initial endowment (a mix of long term borrowing and the transfer of some commercial public assets – such as the profitable land registry), and modest levies on the UK’s massive pool of corporate and personal wealth. The level of private wealth in the UK stands at over six times the size of the economy, up from three times in the 1960s and 1970s. Yet much of this wealth mountain is unearned and increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few. Unlocking some of this wealth for all would enable the building of a much more robust system of income support.

The plan would build towards a new vision for social protection in today’s more turbulent world. It would be a new source of personal empowerment, providing all citizens with much more choice over work, education, training, leisure and caring. For the first time there would be a guaranteed income floor (initially modest, but not insignificant) below which no individual would fall, and a robust income base that would gradually rise over time.

Stewart Lansley is the author, with Howard Reed, of Basic Income for All: From Desirability to Feasibility, Compass. He is also the author of A Sharing Economy, Policy Press, 2016 and Breadline Britain, The Rise of Mass Poverty, Oneworld, 2015 (with Joanna Mack).

If you like this kind of article and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias please donate here. We welcome your support.

Be the first to comment