ETUC analysis finds food delivery companies Deliveroo and Glovo meet all five of the EU Commission criteria for their workers to be considered employees, but Deliveroo describe the analysis as “incorrect and misleading”

The Gig Economy Project, led by Ben Wray, was initiated by BRAVE NEW EUROPE enabling us to provide analysis, updates, ideas, and reports from all across Europe on the Gig Economy. If you have information or ideas to share, please contact Ben on GEP@Braveneweurope.com.

This series of articles concerning the Gig Economy in Europe is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Andrew Wainwright Reform Trust.

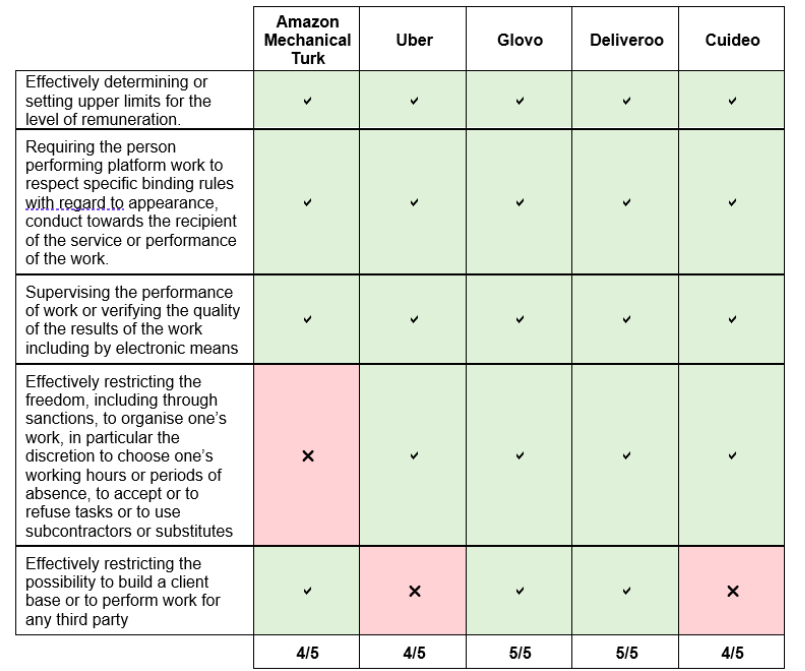

A NEW analysis published by the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC) on Wednesday [25 January] has found that Glovo and Deliveroo meet all of the EU Commission’s draft criteria for employee status, while Uber, Amazon Mechanical Turk and Cuideo meet four of the five criteria.

The EU Commission’s criteria for deciding whether platform workers should be considered independent contractors was a key part of its Platform Work Directive proposals, published in December. The Commission has proposed that if two out of the five criteria is not met, the workers should be considered employees.

The ETUC analysis grades the five companies as follows:

Detailed analysis is provided on each grading (which you can find here), but to take the example of Deliveroo, the British-headquartered food delivery company part-owned by Amazon, the ETUC finds that, on the company effectively determining the pay of riders: “The platform determines the remuneration, and the workers do not know the level of this before accepting the rides, since the information on the duration of the ride (and therefore the payment) is not disclosed. The worker is sanctioned if he refuses a trip after having accepted it.”

On binding rules regarding the performance of the work, the ETUC states: “Ratings given by service recipients are used for the future assignment of work, thus establishing a system of control and discipline based on customer feedback that workers can rebalance under the control of the platform. Workers must use cool bags provided by Deliveroo (against payment) bearing the logo of the digital work platform.”

On supervising the work: “Performance is based on the aforementioned customer rating system.”

On restricting the freedom to organise one’s work: “If workers refuse assignments, the company punishes them by offering them fewer opportunities, or even disconnecting them from the platform. In this regard, evidence exists that after taking holidays, Deliveroo workers have been banned from the platform due to their lack of availability. Another freedom-restricting factor relates to reputation ratings. As they are platform-specific, they lead to “lock-in” effects for workers vis-à-vis that particular platform.”

On restricting the possibility to build a client base or work for a third party: “As is the case on other similar digital work platforms, Deliveroo workers do not participate in the terms and conditions of agreements made with suppliers and customers – they simply deliver the food under the conditions stipulated by Deliveroo.”

Despite these findings, the ETUC described the Commission’s criteria system as “cumbersome” and risked undermining the presumption of employment status contained in the Directive by “opening new loopholes”.

Commenting on the findings, Ludovic Voet, Confederal Secretary of the ETUC, who the Gig Economy Project interviewed in October, said: “Platform companies will work hard and spend huge amounts of money trying to cheat the tests prepared for them by the EU and maintain their exploitation-based business model. But if the animal looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, there’s a good chance it’s a duck. The same goes for employers.

“Things couldn’t be clearer: Europe’s largest platform companies should be seen as employers. If the proposal for a directive does not ultimately apply to large platforms which nevertheless obviously act as employers, what good could this directive be for?”

Last week, Deliveroo CEO Will Shu was quoted in the FT stating that he was “positive about the proposals” as he thought they would “confirm that the majority [of riders] are self-employed. Member states will interpret things differently.”

Deliveroo exited the Spanish market after the Spanish Government’s ‘Riders Law’, which provides a presumption of employment for food delivery couriers, entered into force last August.

Voet added that the response of Shu and other platform CEOs to the Directive “should alert MEPs and ministers”.

“The reaction of the platforms, confident that the directive will confirm that they can operate with freelancers without changing any part of their current mode of operation, should alert MEPs and ministers to the need to strengthen the proposed directive in order that no platform slips through the cracks,” he said.

“It would be good for MPs and ministers to fill in the loopholes in the bill to ensure that the platforms cannot continue to deceive workers and companies that play by the rules. The best the platforms can do would ultimately be to meet with unions to negotiate decent wages and conditions for their workers.”

Leïla Chaibi, MEP for France Insoumise who leads the Left in the European Parliament’s work on the gig economy, said last week that MEPs would be pushing for amendments to the Directive to reduce the number of criteria needed for employment status to just one rather than two, while she expected that in the EU Council, which is made up of heads of the member-states, there would be attempts to push the number of criteria needed in the other direction, to “three, four or five”. Chaibi cited French President Emmanuel Macron’s six-month Presidency of the EU Council as a particular risk in this respect, with Macron thought to be particularly close to the perspective of the platforms.

Commenting on EurActive, a spokesperson for ‘Delivery Platforms Europe’, which is a Brussels lobbyist funded by a number of the largest platforms in Europe, stated: “It’s premature and inappropriate to speculate on how the Commission’s proposal would impact different business models, not least because there is significant room for change between what’s on the table today and the final transposition by member states.”

A Deliveroo spokesperson also said: “This analysis is incorrect and misleading. Courts in European Member States in which Deliveroo operates have repeatedly confirmed that Deliveroo riders are self-employed, including as recently as last December in Belgium.”

The Belgian court verdict, which went against the grain of verdicts across Europe which have generally found that delivery couriers are employees, is currently being appealed by the Brussels Labour Prosecutors Office.

To sign up to the Gig Economy Project’s weekly newsletter, which provides up-to-date analysis and reports on everything that’s happening in the gig economy in Europe, leave your email here.

BRAVE NEW EUROPE has begun its Fundraising Campaign 2021

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Please donate here.

Be the first to comment