A cross-section of papers from the 2021 conference of the International Initiative for the Promotion of Political Economy (IIPPE)

Michael Roberts is an Economist in the City of London and a prolific blogger

Cross-posted from Michael’s Blog

The 2021 conference of the International Initiative for the Promotion of Political Economy (IIPPE) took place a couple of weeks ago, but only now I have had time to review the many papers presented on a range of subjects relating to political economy. IIPPE has become the main channel for Marxist and heterodox’ economists to present their theories and studies in presentations. Historical Materialism conferences also do this, but HM events cover a much wider range of issues for Marxists. The Union for Radical Political Economy sessions at the annual mainstream American Economics Association conference do concentrate on Marxist and heterodox economics contributions, but IIPPE involves many more radical economists from around the world.

That was especially the case this year because the conference was virtual on zoom and not physical (maybe next year?). But there were still many papers on a range of themes guided by various IIPPE working groups. Themes included monetary theory, imperialism, China, social reproduction, financialisation, work, planning under socialism etc. It is obviously not possible to cover all the sessions or themes; so in this post I shall just refer to ones that I attended or participated in.

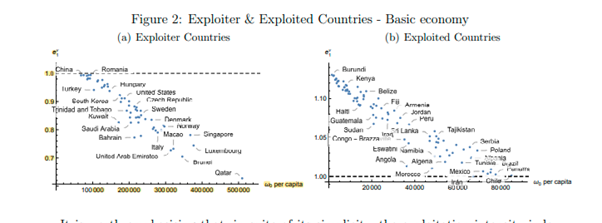

The first theme for me was the nature of modern imperialism with sessions that were organised by the World Economy working group. I presented a paper, entitled The economics of modern imperialism, jointly authored by Guglielmo Carchedi and myself. In the presentation we argue, with evidence, that imperialist countries can be defined economically as those that systematically gain net profit, interest and rents (surplus value) from the rest of the world through trade and investment. These countries are small in number and population (just 13 or so qualify under our definition).

We showed in our presentation that this imperialist bloc (IC in graph below) gets something like 1.5% of GDP each year from ‘unequal exchange’ in trade with the dominated countries (DC in graph) and another 1.5% of GDP from interest, repatriation of profits and rents from its capital investments abroad. As these economies are currently growing at no more than 2-3% a year, this transfer is a sizeable support to capital in imperialist economies.

The imperialist countries are the same ‘usual suspects’ that Lenin identified in his famous work, Imperialism, some 100 years ago. None of the so-called large ‘emerging economies’ are making net gains in trade or investments – indeed they are net losers to the imperialist bloc – and that includes China. Indeed, the imperialist bloc extracts more surplus value out of China than out of many other peripheral economies. The reason is that China is a huge trading nation; and it is also technologically backward compared to the imperialist bloc. So given international market prices, it loses some of the surplus value created by its workers through trade to the more advanced economies. This is the classical Marxist explanation of ‘unequal exchange’ (UE).

But in this session, this explanation of imperialist gains was disputed. John Smith has produced some compelling and devastating accounts of the exploitation of the Global South by the imperialist bloc. In his view, imperialist exploitation is not due to ‘unequal exchange’ in markets between technologically advanced economies (imperialism) and those less advanced (the periphery), but due to ‘super-exploitation’. Workers in the Global South have had their wages driven below even the basic levels for reproduction and this enables imperialist companies to extract huge levels of surplus value through the ‘value chain’ of trade and intra-company mark-ups globally. Smith argued in this session that trying to measure surplus value transfers from trade using official statistics like the GDP of each country was ‘vulgar economics’ which Marx would have rejected because GDP is a distorted measure that leaves out a major part of exploitation of the Global South.

Our view is that, even if GDP does not capture all the exploitation of the Global South, our unequal exchange measure still shows a huge transfer of value from the peripheral dependent economies to the imperialist core. Moreover, our data and measure do not deny that much of this surplus value extraction comes from higher exploitation and lower wages in the Global South. But we say that this is a reaction of Southern capitalists to their inability to compete with the technologically superior North. And remember it is mostly the Southern capitalists that are doing the ‘super exploiting’ not the Northern capitalists. The latter get a share through trade of any extra surplus value from higher rates of exploitation in the South.

Indeed, we show in our paper, the relative contributions to the transfer of surplus value from superior technology (higher organic composition of capital) and from exploitation (rate of surplus value) in our measures. The contribution of superior technology is still the main source of unequal exchange, but the share from different rates of surplus value has risen to nearly half.

Andy Higginbottom in his presentation also rejected the classical Marxist unequal exchange theory of imperialism presented in the Carchedi-Roberts paper, but on different grounds. He reckoned that the equalisation of profit rates through the transfers of individual surplus values into prices of production was inadequately done in our method (which followed Marx). So our method could not be correct or even useful to start with.

In sum, our evidence shows that imperialism is an inherent feature of modern capitalism. Capitalism’s international system mirrors its national system (a system of exploitation): exploitation of less developed economies by the more developed ones. The imperialist countries of the 20th century are unchanged. There are no new imperialist economies. China is not imperialist on our measures. The transfer of surplus value by UE in international trade is mainly due to the technological superiority of companies in the imperialist core but also due to a higher rate of exploitation in the ‘global south’. The transfer of surplus value from the dominated bloc to the imperialist core is rising in dollar terms and as a share of GDP.

In our presentation, we reviewed other methods of measuring ‘unequal exchange’ instead of our ‘prices of production’ method – and there are quite a few. At the conference, there was another session in which Andrea Ricci updated his invaluable work on measuring the transfer of surplus value between the periphery and the imperialist bloc using world input-output tables for the trading sectors and measured in PPP dollars. Roberto Veneziani and colleagues also presented a mainstream general equilibrium model to develop an ‘index of exploitation’ that shows the net transfer of value in trade for countries. Both these studies supported the results of our more ‘temporal’ method.

In Ricci’s study there is a 4% annual net transfer of surplus value in GDP per capita to North America; nearly 15% per capita for Western Europe and near 6% for Japan and East Asia. On the other side, there is net loss of annual per capita GDP for Russia of 17%; China 10%, Latin America 5-10% and 23% for India!

In the Veneziani et al study, “all of the OECD countries are in the core, with exploitation intensity index well below 1 (ie less exploited than exploiting); while nearly all of the African countries are exploited, including the twenty most exploited.” The study puts China on the cusp between exploited and exploited.

On all these measures of imperialist exploitation, China does not fit the bill, as least economically. And that is the conclusion also reached in another session that launched a new book on imperialism by Australian Marxist economist, Sam King. Sam King’s compelling book proposes that Lenin’s thesis was correct in its fundamentals namely, that capitalism had developed into what Lenin called ‘monopoly finance capital’. The world has become polarised into rich and poor countries with no prospect of any of the major poor societies ever making it into the rich league anymore. A hundred years later no country that was poor in 1916 has joined the exclusive imperialist club (save for the exception of Korea and Taiwan, which specifically benefited from the ‘cold war blessings of US imperialism’).

The great hope of the 1990s, as promoted by mainstream development economics that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) would soon join the rich league by the twenty-first century, has proven to be a mirage. These countries remain also-rans and are still subordinated and exploited by the imperialist core. There are no middle-rank economies, halfway between, which could be considered as ‘sub-imperialist’ as some Marxist economists argue. King shows that imperialism is alive and not so well for the world’s people. And the gap between the imperialist economies and the rest is not narrowing – on the contrary. And that includes China, which will not join the imperialist club.

Talking of China, there were several sessions on China organised by the IIPPE China working group. The sessions were recorded and are available to view on the IIPPE China You tube channel. The session covered China’s state system; its foreign investment policies; the role and form of planning in China and how China dealt with the COVID pandemic.

There was also a session on Is China capitalist?, in which I submitted a presentation entitled, When did China become capitalist? The title is a bit tongue in cheek, because I argued that since the 1949 revolution that threw out the comprador landlords and capitalists (who fled to Formosa-Taiwan), China has no longer been capitalist. The capitalist mode of production does not dominate in the Chinese economy even after the Deng market reforms in 1978. In my opinion, China is a ‘transitional economy’ like the Soviet Union was, or North Korea and Cuba are now.

In my presentation, I define what a transitional economy is, as Marx and Engels saw it. China does not meet all the criteria: in particular, there is no workers democracy, no equalisation or restrictions on incomes; and the large capitalist sector is not steadily diminishing. But on the other hand, capitalists do not control the state machine, the Communist party officials do; the law of value (profit) and markets do not dominate investment, the large state sector does; and that sector (and the capitalist sector) are under an obligation to meet national planning targets (at the expense of profitability, if necessary).

If China were just another capitalist economy, how do we explain its phenomenal success in economic growth, taking 850m Chinese off the poverty line?; and avoiding any economic slumps that the major capitalist economies have suffered on a regular basis? If it has achieved this with a population of 1.4bn and yet it is capitalist, then it suggests that there can be a new stage in capitalist expansion based on some state-form of capitalism that is way more successful than previous capitalisms and certainly more than its peers in India, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia or South Africa. China would then be a refutation of Marxist crisis theory and a justification for capitalism. Fortunately, we can put China’s success down to its dominant state sector for investment and planning, not to capitalist production for profit and the market.

For me, China is in a ‘trapped transition’. It is not capitalist (yet) but it is not moving towards socialism, where the mode of production is through collective ownership of the means of production for social need with direct consumption without markets, exchange or money. China is trapped because it is still backward technologically and is surrounded by increasingly hostile imperialist economies; but it is also trapped because democratic workers organisations do not exist and the CP bureaucrats decide everything, often with disastrous results.

Of course, this view of China is a minority one. Western ‘China experts’ are in one voice that China is capitalist and a nasty form of capitalism to boot, not like the ‘liberal democratic’ capitalisms of the G7. Also, the majority of Marxists agree that China is capitalist and even imperialist. At the session, Walter Daum argued that, even if the economic evidence suggests that China is not imperialist, politically China is imperialist, with its aggressive policies towards neighbouring states, its exploitative trade and credit relations with poor countries and its suppression of ethnic minorities like the Uyghars in Xinjiang province. Other presenters, like Dic Lo and China’s Cheng Enfu, did not agree with Daum, with Cheng characterising China as “socialist with elements of state capitalism”, an odd formulation that sounds confusing.

Finally, I must mention a few other presentations. First, on the vexed question of financialisation. The supporters of ‘financialisation’ argue that capitalism has changed over the last 50 years from a production-oriented economy into one dominated by the finance sector and it is the vicissitudes of this unstable sector that cause crises, not the problems of profitability in the productive sectors, as Marx argued. This theory has dominated the thinking of post-Keynesian and Marxist economists in the last few decades. But there is plenty of growing evidence that the theory is not only wrong theoretically but also empirically.

And at IIPPE, Turan Subasat and Stavros Mavroudeas presented yet more empirical evidence to question ‘financialisation’ in their paper entitled: The financialization hypothesis: a theoretical and empirical critique. Subasat and Mavroudeas find that the claim that most of the largest multinational companies are ‘financial’ is wrong. Indeed, the share of finance in the US and the UK has not increased over the last 50 years; and over the last 30 years, the financial sector share in GDP declined by 51.2% and the financial sector share in services declined 65.9% in the countries studied. And there is no evidence that the expansion in the financial sector is a significant predictor of the decline in the manufacturing industry, which has been caused by other factors (globalisation and technical change).

And there were some papers that continued to confirm Marx’s monetary theory, namely that interest rates are not determined by some ‘natural rate of interest’ from the supply and demand of savings (as the Austrians argue) or by liquidity preference ie hoarding of money (as the Keynesians claim), but are limited and driven by movements in the profitability of capital and thus the demand for investment funds. Nikos Stravelakis offered a paper, A Reconciliation of Marx’s Theory of Interest and the Risk Premium Puzzle that showed corporate net profits are positively related to bank deposits and net to gross profits are positively related to the loan deposit ratio and that 60% of the variations in the interest rates can be explained by changes in the rate of profit. And Karl Beitel showed the close connection between the long-term movement of profitability in the major economies in the last 100 years (falling) and the rate of interest on long-term bonds (falling). This suggests that there is a maximum level of interest rates, as Marx argued, determined by the rate of profit on productive capital, because interest comes only from surplus value.

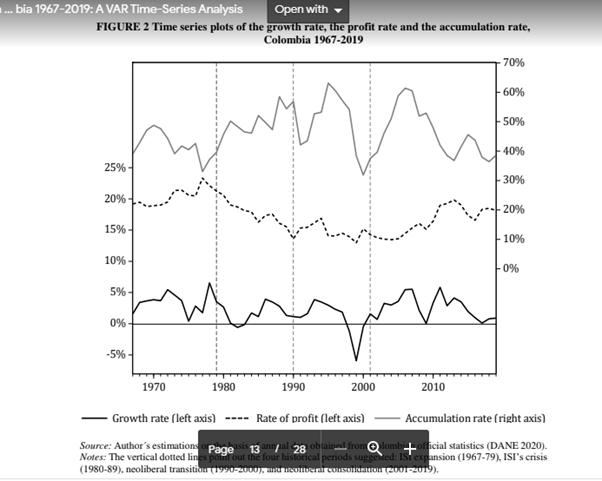

Finally, something that was not at IIPPE but adds yet more support for Marx’s law of the tendency of the profit rate to fall. In the book, World in Crisis, co-edited by Carchedi and me, lots of Marxist economists presented empirical evidence of the falling rate of profit on capital from many different countries. Now we can add yet another. In a new paper, Economic Growth and the Rate of Profit in Colombia 1967-2019, Alberto Carlos Duque from Colombia shows the same story as we have found elsewhere. The paper finds that the movement in the rate of profit is “in concordance with Marxian theory predictions, and affects positively the growth rate. And the GDP growth rate is affected by the profit rate and the accumulation rate is in an inverse relationship between these last variables.”

So the results “are consistent with and provide empirical support for the Marxian macroeconomic models reviewed in this paper. In those models, the growth rate is a process driven by the behaviour of the rate of accumulation and rate of profit. Our econometrical analyses provide empirical support for the Marxian claim about the fundamental role of the rate of profit, and its constituent elements, in the accumulation of capital and, consequently, in the economic growth.”

Be the first to comment