Jim Hansen and team shatter optimism

Wolfgang Knorr is a climate scientist, consultant for the European Space Agency and guest researcher at the Department of Geography and Ecosystem Science, Lund University

Cross-posted from Wolfgang’s Substack

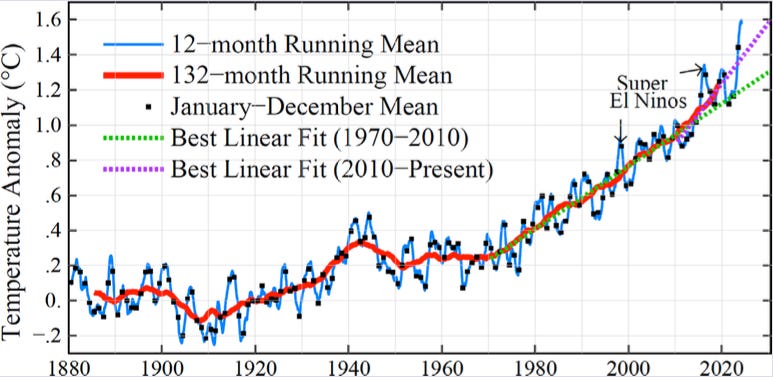

Sometimes, pictures can say more than a thousand words. Or curves on graphs can. And while the world is still debating whether 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming is still technically feasible, Jim Hansen and coworkers make a prediction that temperatures will stay above +1.5°C for the coming decades. Which means that we are already on a planet where we find the goal of the Paris Agreement in the rear mirror (the goal to limit temperature rise to “ideally” 1.5°C).

Today (February 6, 2025), a Financial Times headline reads “Hottest January on record shocks scientists”. The background is that while climate scientists have been busy speculating about the reasons of the sudden jump in the Earth’s surface temperature that happened between 2023 and 2024, many believed that come 2025, things would cool down at least a little. As Berkeley climate scientist Zeke Hausfather explains, an acceleration of climate warming has been expected based on climate model simulations, and the jump might just have been a confluence of several factors, similar to but in an opposite direction to an earlier phase during 1998 to 2012, where warming had slowed down dramatically, in a way not predicted by climate models. Some of the recent jump has been attributed to warm El Niño conditions in the Pacific Ocean, and by December of last year, the Pacific by had entered into a cold, ‘La Niña’ phase.

So to some climate scientists, the new data might have indeed come as a shock. But the impression the article leaves – that climate science itself is now in shock – is demonstrably wrong. Three days ago, Jim Hansen – pioneer of both climate modelling and climate activism – together with 17 colleagues published a paper (see figure) where they provide, for the first time, a full explanation for why global mean temperatures have recently made a massive upward jump of 0.4°C, coupled to the testable hypothesis that in the coming decades, temperatures will hardly decrease back below 1.5°C above. This would mean that we have passed the desired global warming limit set by the Paris Agreement at least ten years ahead of schedule. Since the Paris goal refers to climate and not weather, it is not enough to exceed the limit for a single year, as happened in 2024. We need to stay on average above 1.5 for at least a twenty-year period. According to Hansen and colleagues, this period has now begun.

Jim Hansen has, for some time, been arguing that planet Earth reacts to increased levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases more strongly than what is believed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In 2023, Hansen led a paper arguing that past climate changes have been given too little attention compared to model simulations. At the same time, models that tend to underestimate the greenhouse gas warming tend also to underestimate the cooling effect from aerosols, tiny airborne particles from fires and other pollution that reflect sunlight. Too little warming by CO2 & co plus too little cooling by air pollution can still get you the right answer. The problem arises when the cooling effect is taken away: then, the warming will be larger than expected.

And that is what happened after 2010: new shipping regulations led to a stark decrease in the sulfur load of shipping fuel and cleaned up the skies over shipping lanes. Since those marine environments mostly have clean air without the ships, the effect is much larger here than over land areas that are usually more polluted anyway. According to Hansen’s team, this was the main effect that led to sudden warming. The good news is that the warming will eventually slow down and not spiral out of control.

This conclusion rests on the interpretation of satellite data that show large parts of the globe absorb markedly more sunlight since 2010: the Earth seen from space has become darker. The main darkening areas coincide with the main areas where emissions from ships had become cleaner. On average, the earth has become darker by 0.5%, which translates into an additional heating rate of 1.7 Watts per square meter. This is a lot, roughly half the net heating rate – or ‘radiative forcing’ – created by all greenhouse gases and aerosols combined according to the IPCC. While some of the heating is climate feedback – warmer weather accompanied by fewer clouds, reflecting less sunlight – an astonishing 0.5 Watts per square meter is the result of cleaner shipping fuels, according to Hansen and coworker’s analysis of spatial patterns of aerosol and sea surface temperature changes.

The new publication goes on to argue that the IPCC has been generally over-reliant on models, and that the Earth will likely warm significantly faster than what we have been told. As a result, we are fast approaching a point of no return, because large parts of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets in direct contact with ocean water are vulnerable to melting even with moderate warming. This could mean 15 to 25 meters of sea level rise in the long term, with several meters within a single century. Apart from more violent and unpredictable weather, we as humanity would find ourselves in a situation where permanent settlement of low lying coastal areas becomes impossible. Since such areas tend to be densely populated and provide a large part of agricultural produce, this will have devastating consequences for geopolitical stability and human welfare.

How reliable are the results? The problem is that Hansen and coworkers’ estimate of the effect of the shipping fuel clean-up from simple analysis is much higher than the 0.07 to 0.15 Watts per square meter calculated by several studies using complex computer simulations. Gavin Schmidt, Hansen’s successor as the head of NASA’s Goddard institute, also thinks that Hansen’s analysis is too simple and neglects year-to-year variations as well as Chinese emissions.

But a general distrust of complex models is something that pervades Hansen’s thought. The same applies to his insistence that the sensitivity of the Earth’s temperature to rises in greenhouse gases is higher than what most modelers tend to believe. So why the distrust?

Hansen is not just some climate scientist, but among the living climate scientists probably the one with the longest experience with climate modeling – and also with active engagement in politics. To put things in perspective: At the time I entered climate science in 1992, there were no more than three fully fledged climate modelling institutions, and one ascendant newcomer. There were the National Center for Atmospheric Research and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in the US, the venerable Met Office with its Hadley Centre in the UK, and the newcomer, the Max-Planck-Institute (MPI) for Meteorology in Hamburg, which I was to enter as a doctoral candidate.

One thing that is now often overlooked is that a distrust of models is something that has been quite common among the older generation of climate scientists. At the MPI, both directors were model skeptics. Klaus Hasselmann, who was later awarded half of the first Nobel prize in physics for work in climate science, and Lennart Bengtsson, who had moved to Hamburg from the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, to build Germany’s own climate model. Hasselmann never used climate models for prediction, but only as a tool, in particular for his ‘optimal fingerprint’ technique, a method he and many others successfully applied to detect the effect of human action within climate warming data.

It was this, and not climate prediction, that had convinced the Nobel committee. Bengtsson, on the other hand, would repeatedly lecture us not to ever trust climate model simulations of changes in rainfall, and told us that the most simple statistical approaches would be superior. My PhD advisor, Martin Heimann, together with his own advisor, the late Charles Keeling, the originator of the famous Keeling curve, had built models of the global carbon cycle that were both simple and meticulously calibrated and validated against a whole range of observational data.

Hansen had already run climate predictions in 1984, and used them four years later for his first and most famous testimony before the US Congress, which had been instrumental for creating the IPCC. In hindsight, those predictions proved to be remarkably accurate. In his later work, Hansen still uses climate models, but almost always in auxiliary roles, more as a tool rather than as a black box for looking into the future.

This prudence and general reservation against modeling has now largely gone. Since about the year 2000, climate models have come to be known as so-called ‘Earth System’ models, horrendously complex but in some aspects utterly simplistic. These models would contain for example a mathematical model of plants and soils, as well as that of atmospheric and ocean flow. An example that has become well known in the climate research community is a simulation by a team from the Hadley Centre that predicted a rapid collapse of the Amazon rainforest as a result of climate warming – but the whole effect was based on a few simple equations that related carbon loss of soils to temperature, and a very simple temperature threshold above which it was assumed that plants would stop doing photosynthesis. In the real world, however, plants are far more adaptive then that. But since the results were spectacular and garnered a lot of attention, the race has since been on to create the most complex models.

It is Hansen’s distrust of models based on long-time experience as opposed to what I believe is a subtle but real tendency to see complex models as by definition superior that makes me wonder if it is more prudent to trust in Hansen’s intuition than in the wisdom of the modeling mainstream. I believe there is a real possibility that he and his collaborators are right. And it would not be the first time – earlier he had strongly criticized the IPCC for assuming that ice shelf melting would proceed linearly, and suggested using an exponential increase in the absence of more accurate models. He has proved mostly right since estimates of the risk of sea level rise have been constantly corrected upwards.

What that means is that we could see a shutdown of major ocean currents in the Atlantic that today transport massive amounts of heat polewards, and as a result cooling surface and warming deeper oceans. Since large parts of the Antarctic and, to some extent, Greenland ice sheets rest on bedrock that is below sea level, this could lead to a rapid acceleration of ice shelf disintegration and much faster sea level rise than currently anticipated. Once this has been set in motion there is essentially nothing that could stop it. This is what the authors call the ‘point of no return’.

Are they exaggerating? I fear not. Since his retirement in 2013, Hansen has set himself the goal of producing meticulously crafted and extremely comprehensive scientific articles that also contain a political appeal. They are essentially mini climate assessments, and it is no coincidence that they are written in a way that they can be used as such – Hansen has never formally contributed to any of the IPCC reports. His approach is to tell it ‘as it is’ but at the same time to leave room for hopeful messages. This is why in his latest article, he discusses at length options such as nuclear power or artificial climate cooling by spraying aerosols. The risk of several meters of sea level is suggested by the simple observation that it happened several times when the last ice age was ending, and that during the Eemian, the last warm period before the previous ice age, a large part of the Western Antarctic ice shelf had very likely been gone. But we have warmed Earth already well past Eemian climate change and are on a path to 2°C warming in only 20 years’ time. As the authors restate, the last time this happened – albeit for a very long time – all ice sheets that rest on bedrock below sea level had probably gone. If even the much more subtle climate warming that happened during the Eemian had led to a major ice sheet integration, then the those ice sheets must be intrinsically unstable. It is therefore difficult to conceive of a scenario where we would be able to escape this ‘point of no return’. And this may be the point where the authors are even too optimistic. Their attempt to convey a positive message that leaves the younger generation with options is palpable.

Thanks for reading Climate Uncensored! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Be the first to comment