The Gig Economy Project speaks to Paris Marx, host of the Tech Won’t Save Us podcast and author of new book ‘Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong about the Future of Transportation’, about the Uber Files and why the company’s vision for transforming transport for the greater good has not come to fruition. This interview is available as a podcast and in text form.

The Gig Economy Project, led by Ben Wray, was initiated by BRAVE NEW EUROPE enabling us to provide analysis, updates, ideas, and reports from all across Europe on the Gig Economy. If you have information or ideas to share, please contact Ben on GEP@Braveneweurope.com.

This series of articles concerning the Gig Economy in Europe is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Andrew Wainwright Reform Trust.

THE Uber Files revelations have let a thousand questions bloom about this Silicon Valley company that has broken all the rules, accumulated massive power over cities across the globe, but has never achieved a profit, and has so far failed in many of its stated ambitions to transform the transport sector for good.

To begin to piece together some answers, the Gig Economy Project spoke to Paris Marx, host of the popular ‘Tech Won’t Save Us’ podcast and author of new book ‘Road to Nowhere: What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong about the Future of Transportation’, published by Verso in July.

In this podcast, we discuss:

01:04: Key takeaways from the Uber Files and the reaction to it

12:15: Silicon Valley’s vision for transport and why it has failed

26:55: What changes should we make to the transport system?

34:28: What next for Uber?

AN ABBREVIATED TEXT VERSION OF THIS INTERVIEW IS AVAILABLE BELOW

The Gig Economy Project: For someone like yourself who has been watching Uber closely the revelations in the Uber Files perhaps won’t have been a complete surprise, but what were the main takeaways for you?

Paris Marx: There was a lot in there that we already knew about, the focus on ‘greyball’ and ‘kill switch’ are very much things we knew here in Canada. I believe it was the Toronto Star which wrote their article on the Uber Files and started it off with how the kill switch was used in Montreal when tax authorities raided the Uber office there to try to get files. The HQ used the computers to shutdown and encrypt everything, and basically the same story had been written a few years ago. Certainly we found out that it was used in cities that we didn’t know of before.

I think the real novel contribution of the Uber Files was to see how easy it was for Uber to get in the room with prominent politicians. We already knew Uber had relationships with a lot of politicians, this is not new information, we knew that they had paid academics to publish really favourable reports to make Uber look good as well. But I think that because it was leaked by Mark MacGann, who was a top Uber person in Europe and the Middle East, the Uber Files illustrated how easy it was to get in the room and how politicians were really keen to buy the narrative that Uber was selling, they really wanted to believe the techno-vision that it was putting forward, that it was the future of work and transportation, and were really willing to ignore the many potential downsides of this model, even as that information was coming out.

So in France, Emmanuel Macron [current President] was working to ensure that Uber could operate there. People who previously worked in the Obama administration started working for Uber and used their contacts with the US Government and even with ambassadors in France and the Netherlands to ensure that Uber wouldn’t be restricted in those countries. And we saw in the UK the then-Chancellor George Osborne was meeting with Uber. In Canada the mayor of Toronto was known to have met with Uber and Toronto was one of the first jurisdictions to have regulated Uber but those regulations were exactly the sort of things that Uber wanted, it basically copied Uber’s model and implemented that.

There’s many examples of these things happening so I think that it’s important that we understand there is a degree to which Uber was able to convince these politicians that it was the future and the degree to which the politicians wanted to believe that or were opening to believe that without thinking critically about the consequences.

GEP: I’m interested in getting your thoughts on the reaction to the Uber Files, from someone on the other side of the pond, because a lot of the revelations were centred on Europe. What has the reaction been in the US, where Uber is actually headquartered; my sense is that it’s gone under the radar to some extent?

Paris Marx: I would pretty much agree with you. Here in Canada, the Toronto Star and CBC published articles on it and the mayor of Toronto made a statement that he didn’t do anything wrong and was one of the first ones to regulate, and he was able to get away with that type of boiler plate statement. In the US I would say similarly, the Washington Post has published a number of revelations from the Uber Files, similar stuff as was published in The Guardian, but they don’t seem to have hit.

There doesn’t seem to have been a significant impact in forcing people to challenge Uber or see Uber in a different light because a lot of these things were things we already knew about Uber, but also Uber has had an effective PR line in saying that ‘these are things from the Kalinick era, we have already moved on from this, we have a new CEO and we’ve fixed all our problems now’, these are the lies they put out there. And that’s been effective in getting around the story. It really felt that the story hit, there was a few days where people were interested, and then the interest died down.

I don’t know if it’s been similar in Europe, I know there’s been discussions about investigating Macron as a result of these revelations, and there was the official in the European Commission who was in the papers as well, but I haven’t seen if things have moved forward on those fronts.

GEP: I think there’s things happening, there’s inquiries happening in quite a lot of different European countries into how Uber entered into the national market, there’s an inquiry into Neelie Kroes who was the European Commission vice-president, who was essentially working on behalf of Uber inside and after her time at the Commission. There was also a big taxi protest and strike in Italy which was actually part of bringing down the Italian Government, and now there’s going to be an election there. There’s been things happening but I think it has dissipated quite quickly.

I think you are right in identifying that Uber have been able to say this is something from the past and is not Uber now: why is that incorrect?

Paris Marx: It’s playing on this narrative that Uber has been able to weave for itself where during the Travis Kalinick era, and he was ousted from the company in 2016-17, there was this culture where anything goes, they were happy to break the laws, there was rampant sexism and discrimination within the company itself. The way that Uber has told its own story is that once these things reached a crisis point they finally turned on Travis Kalinick and they brought in Dara Khosrowshahi to replace him, he was at Expedia before. The explanation is that when Khosrowshahi came in he changed the company, he changed the culture of the company, he started to work with drivers to ensure they had better conditions, they started to work more collaboratively with cities, and so forth.

What we actually see is that is kind of bullshit. I’m sure there have been changes internally at the company, I certainly hope that women aren’t treated the way they were under Kalinick and those things have changed, and I feel like I haven’t heard as much about those kind of aspects of the company since Khosrowshahi took over and that is a positive development. However, in taking over and weaving that narrative, Khosrowshahi has also been able to whitewash the ongoing campaign that the company has against workers.

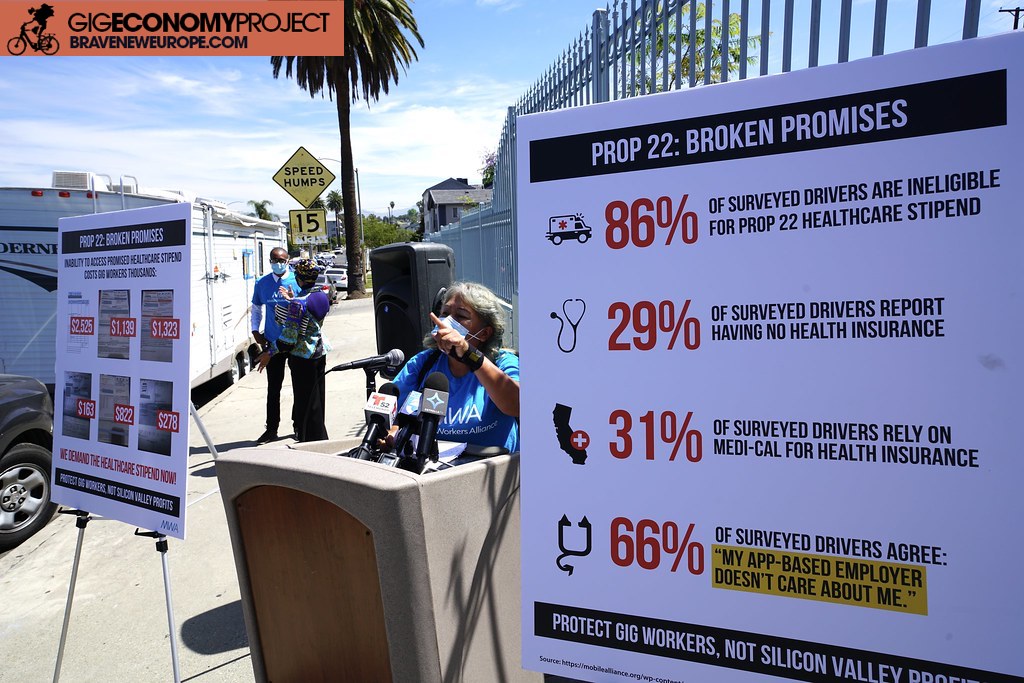

In particular we see that most prominently in California with the Proposition 22 campaign, which was all about overturning the law that the government had passed to make these Uber drivers and all other gig workers employees instead of independent contractors. By effectively lying to the public and spending hundreds of millions of dollars to mislead the public, they were able to overturn that with this ballot measure which wrote a third classification of workers in there, who were independent contractors but weren’t employees so you were effectively a contractor with a few more benefits that most of the workers said they couldn’t actually access in the end anyway, and many have said they are actually worst off after this law has been passed.

Now what we see is after doing that in California, Uber has rolled out a campaign to bulldoze this through in many other jurisdictions, so states in the US – there’s been progress in Washington State recently, they’ve had some trouble in Massachusetts – and they’ve been trying in Canada, Ontario. In the UK we had the Supreme Court decision last year, which found that Uber drivers were workers, not independent contractors, but the Supreme Court said they should be paid for the entire time from log-on to log-off and Uber just ignored that because they are trying to re-write that worker status to be what they want it to be and to serve their business model.

Certainly there have been pushes in other countries for an employment model, but this clean and softer image the company is pushing is trying to hide the concerted war on workers which continues under Dara Khosrowshahi’s leadership, and that really is essential for the company to ever be able to turn a profit and have some kind of sustainable business, they do not want to have to pay workers a fair wage and treat them as they should be treated.

GEP: Let’s talk about your book, ‘Road to Nowhere: What silicon valley gets wrong about the future of transportation’. What is Silicon Valley’s big idea to change transport and what’s wrong with that idea?

Paris Marx: Really what Silicon Valley has been pushing for more than a decade now when it comes to transportation and their contribution to transportation is that they recognise that there are these problems, particularly in North America where transportation is really dominated by the automobile. They say ‘okay we can see that there’s a contribution to climate change, we can see that people are stuck in traffic, we can see that people are dying on the roads and this needs to be rectified. The solution is to think of new technologies and add new technologies to the automobile that are supposed to solve these problems.’ Uber and ridehailing will mean you won’t have to own a vehicle anymore, it will solve traffic problems, it will make transportation more accessible to people who can’t access it, and self-driving cars are an extension of that, promising many of the same things.

And what we actually see and can observe, because many of these things have been around for quite awhile now, particularly Uber, is that these promises tend not to be realised. So Uber, even though they made all these promises, in fact they’ve made traffic worse in cities, they’ve done very little to reduce car ownership and car use, meanwhile they pulled people away from public transit and increased the climate contributions: if you are taking Uber it’s emitting more than if you just used the transport mode you had used previously. Self-driving cars have really not arrived, sure there are a few from around the world, really in a test phase, but they didn’t takeover the transportation system as was promised.

So, the real contribution on the part of the tech industry is to say: ‘There’s all these problems with automobility, but we can solve that by integrating these new technologies into the car itself, so we can still be reliant on our cars and don’t need to change the fundamentals of this system. We don’t need to think about politics, because we can just change things with technology.’

But really, if we are going to solve these problems, as many of the failures of these tech companies have shown us, what we need is to address the politics of transportation.

GEP: In terms of Uber specifically, the company is in many ways remarkable because it managed to attract unprecedented venture capital investment, it’s pre-IPO investment was 2500 times that of Amazon. Yet it never offered any technology which changes fundamentally the unit economics of driving a cab, because a lot of what goes into the economics of driving a cab is the vehicle, the driver and the fuel, and Uber doesn’t really change any of that.

In the book you compare Uber to Amazon, and explain why Uber has failed in a growth-before-profits model, whereas Amazon has succeeded. Can you explain that?

Paris Marx: Amazon is the company that a lot of other companies which want to find out how to build their way into a monopoly try to emulate. And it worked for Amazon because at its core its an e-commerce business, so it could take advantage of economies of scale as it grew larger, because the cost of delivering a service could be reduced over time. That was really key for Amazon to pull this off, to have this model work for it, and to become this massive juggernaut that it is today. It used it’s profits from e-commerce and AWS cloud computing in order to expand into all these other industries because it has built this monopoly or oligopoly, whatever you want to call it, which means it has this significant degree of control which allows it to extract huge amounts of profit and revenue from these industries and from these services it commands.

So naturally Uber wanted to emulate that, it wanted to control their market segments and ‘lose their way to growth’: lose a ton of money so they could grow very quickly and takeover in a similar way to Amazon. As you were saying, this doesn’t really work for a company like Uber because of the service that they provide, a taxi service effectively, which they do less efficiently than an existing taxi service, which has a fleet of vehicles it manages and an insurance which tends to cover the fleet. With Uber, it forced every single individual driver to own their own vehicle, to buy their own insurance, to get their own gas and maintenance, so there was no kind of efficiencies that were developed there.

As it grew larger, that didn’t really change – sure they controlled the app and were able to deploy the app in a ton of different places, but the fundamentals of the service – the main cost areas – were less efficient than a taxi service. And then on top of that Uber has these really expensive headquarters all over the world, these expensive software engineers and development teams, these incredibly highly compensated CEO and executive teams, that a regular taxi company wouldn’t have.

So you can see how an Uber model was less efficient and thus was not able to emulate Amazon because it was operating in a whole different sector that wasn’t able to take advantages of economies of scale in the same way because of how it’s designed. That’s why Uber couldn’t emulate Amazon and instead has continued to lose billions and billions of dollars over the years as it tried to achieve this.

Now, finally it seems it’s going to have to change and is having to reckon with what that’s going to look like, as the access to cheap money starts to dry up and interest rates go up and things like that.

GEP: Even though Uber has burned through $31 billion, even though Uber’s share price is less now than at the original IPO, have the original investors benefited financially from putting their money into Uber?

Paris Marx: Yeah absolutely. The early investors got in at a really low price, and then even though when it went public the price didn’t shoot-up as much as they were expecting it to, they were still able to cash out and make profits on their investment because of the stage in which they invested into the company. Effectively they were offloading the risk of what was coming with Uber in the future onto retail investors, these people who wouldn’t have been investing early in the company. The early investors have absolutely made their money back, they have certainly benefited.

But has Uber really benefited society? I would say no, it’s certainly benefited some people to make it more easy to get a taxi, but as studies have shown the people who have mainly benefited were young, college educated people in urban areas, earning above average incomes. Basically your average tech worker. It’s not the underserved or marginalised people as some of the marketing would have you believe, it’s people who are already well-off who already have good access to transportation services who are just having it further improved for them as a result of this service. And now as we are seeing Uber’s prices rise, it’s going to be those types of people who continue benefiting from the service, and less and less the broader public and anyone else who would be using it.

But I’d note one other thing here as well. When we’re thinking about who benefited from Uber, one of the things that showed up in my research for the book, and this is something that Hubert Horan who is a frequent critic of Uber has noted, is that Uber adopted a playbook that was developed in the 1990s by libertarian organisations, right-wing groups, the Koch brothers, to deregulate the taxi industry in the United States. And it picked this up to benefit itself, to destroy the taxi regulations, and to build this monopoly on transportation around the world.

So as that’s progressed and as we’ve seen this war on workers in so many countries, yes the early investors have benefited from this, but I’d say that even if Uber doesn’t turn a profit at the end of the day, there’s a lot of other capitalists who have also benefited from what Uber has done in chipping away at taxi regulations but also labour regulations in many countries and jurisdictions.

GEP: So Uber’s historic role might not be to transform the taxi industry, it might be to weaken workers’ rights and change the nature of the labour relationship?

Paris Marx: Absolutely, and I’d say it’s not just an Uber thing. If you look at what many of these tech companies have done – Amazon for example – what many of their innovations entail, it really is to find ways to reduce the power of workers, to enhance the role of exploitative management practices, to ensure workers are paid less, and so forth.

GEP: An important part of the book is to look at what actually are the solutions to the massive problems with transport right now – congestion, pollution, carbon emissions. Some of these have been worsened by Uber and co, but they were there anyway. So what is the alternative to Silicon Valley’s solution for transport?

Paris Marx: These are problems that we need to address and we need to be serious about what the solutions can be, especially after a decade of Silicon Valley selling us these ideas of what the solutions could be and then finding that they were unable to follow through, and in many ways their solutions were worse not better.

So the key is that it’s not just rolling out new technologies or attaching new technologies to cars that are going to solve the problems, ultimately these are political problems that require political solutions in terms of how we define our transportation system and how we distribute the benefits of that transportation system.

Certainly I would argue that a lot of mistakes were made by placing such a huge emphasis on automobiles in the past, at the expense of transit and other collective services. So if we are thinking what’s going to solve these things, what’s going to solve the traffic, what’s going to solve the personal cost of owning a car which is very expensive for a lot of people, and the lack of access to public transportation that a lot of people experience, it’s really by making a much greater investment in public transportation systems. Whether that’s by expanding subways, making buses more reliable, more frequent, more available in more areas. And making them more affordable as well, because even a city with a pretty good public transport system, like the tube in London, the fare can be prohibitively expensive.

Then also making the investment in things like cycling infrastructure so people can reliably use a bike and not feel like they are going to be run down by a car or there bike is going to be stolen if they go into a store. Even in Paris through the pandemic there has been a significant increase in cycling because the government took concerted efforts to close streets, to provide more space for bikes, and to encourage people to use them.

Also, we need to build communities in a way where things aren’t quite so spread out, things are closer to where you are living, and that also requires thinking beyond transportation. So yes we need to address the transportation system, but we also need to recognise that that’s just one system in a whole group of systems that we depend on in our everyday lives. If we improve transportation in our neighbourhoods but that then causes housing prices to go up and pushes people out who would most benefit from those changes, then that’s not really moving us in the right direction either. So we need to pay attention to how a privatised housing system doesn’t really fit into this broader vision, and that’s going to require greater investment in things like public housing and co-operative housing to ensure that people can afford to live in these communities.

GEP: What about electric cars, because Elon Musk would have it that electric cars is really the answer to climate change issues and transportation issues. What role do electric cars have to play in a just transition to a zero-carbon economy?

Paris Marx: I think that electric cars certainly have a part to play, I think electrification is going to be really important for this kind of transition. But what I’m worried about right now is the over-emphasis on electric cars by people like Elon Musk but also many western governments, which are really pushing the electric car as the silver bullet to transportations contribution to climate change. I think that’s really misleading, because it doesn’t address how there are all these other problems created by having a transportation system that is so reliant on cars, from the sprawling neighbourhoods to the air pollution which is still going to happen with electric cars, to the people who die on the roads, and on and on.

I also think the environmental benefits of electric cars is over-stated. There’s no question at all that in most cases the electric car is going to be better than the internal combustion engine vehicle, it’s going to have a lower lifecycle of emissions, absolutely. But it’s still a car, it still has an environmental impact, and in particular we see that in the amount of mining that is going to be necessary to make all these cars around the world. Certainly, there are pushes to increase the amount of mining in the global north, like the US, like Canada, like Portugal in the EU, where there is pushes to increase mining for electric battery consumption. But most of that mining is going to be in the global south, in places that we have taken advantage of for centuries to extract mineral resources from, and those mines have consequences for local communities, for the environment and for workers.

So the electric vehicle is certainly part of the solution, there’s certainly going to be places in particular in rural areas where electric vehicles will be necessary, but in cities and suburban areas especially I think there needs to be much greater focus on alternatives to the car.

GEP: Finally Paris, the world in which Uber and many other tech firms were born into in the early 2010s is disappearing – we suddenly have high inflation, interest rates are rising, the era of cheap money is over and investors have suddenly stopped flooding tech start-up’s with cash. Uber also have problems with the rising cost of fuel, and they are having to increase the price of fares. What’s next for Uber?

Paris Marx: During the pandemic we started to get an idea of what the next stage of Uber is going to look like, and things have only moved further in that direction as they lose access to cheap money as interest rates go up. The price of Ubers are going up, to the degree that taxis are even more affordable than Ubers for some trips now in a way that they weren’t before because of how heavily Uber was subsidising its trips. On top of that, Uber’s service is also becoming less convenient because it is running out of the supply of labour that is willing to be exploited by going on to the platform and accept the terrible terms Uber provides for these workers.

So it’s more expensive, it’s less convenient, and therefore how does Uber respond to that, how does it maintain the hold on transportation that it had in the past? One of the things I’m concerned about now is that Uber is making deals with taxi companies in cities like New York, San Francisco, even in countries like Italy, to bring taxis onto the app. Before Uber was at war with the taxi companies, now they are bringing them into the app, so I’m concerned that after decimating the rights and protections of these workers, after decimating the regulatory structure of the taxi companies, that Uber is basically going to try to now subject the taxi drivers, as a pool of labour willing to be on Uber’s app, to its own idea of what the rules for the taxi industry should be by further reducing the compensation for those workers, their rights, but at the same time subjecting even taxi drivers to surge pricing and the other things that Uber has innovated, so to speak, through its model.

I don’t think it’s a positive future if Uber is able to attain these things, and it shows why the fight against Uber needs to continue to ensure that workers are recognised as employees and have the rights that they want. But also at the same time that we don’t allow Uber to write the rules for how transportation works in the city or how taxi services work in the city, and that should be regulated by the governments and in collaboration with other people who will be affected by this.

To sign up to the Gig Economy Project’s weekly newsletter, which provides up-to-date analysis and reports on everything that’s happening in the gig economy in Europe, leave your email here.

Support us and become part of a media that takes responsibility for society

BRAVE NEW EUROPE is a not-for-profit educational platform for economics, politics, and climate change that brings authors at the cutting edge of progressive thought together with activists and others with articles like this. If you would like to support our work and want to see more writing free of state or corporate media bias and free of charge. To maintain the impetus and impartiality we need fresh funds every month. Three hundred donors, giving £5 or 5 euros a month would bring us close to £1,500 monthly, which is enough to keep us ticking over.

Be the first to comment