Pursuing Alternatives to Zero-Sum Bloc Politics

Glenn Diesen is a professor of political science at the University of South-Eastern Norway (USN), Professor with research focus on geoeconomics, Russian foreign policy and Eurasian integration

Cross-posted from Glenn’s Substack

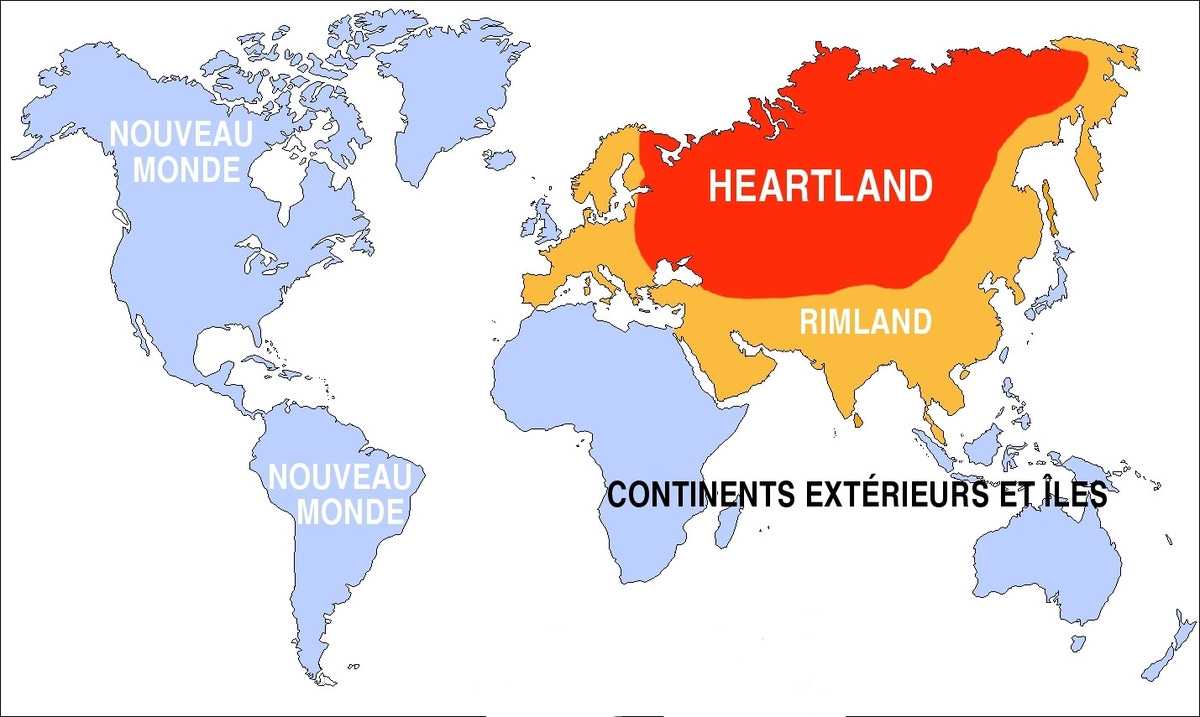

Geopolitics has traditionally focused on Eurasia as the vast continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific has the largest share of territory, population, and resources. Halford Mackinder’s heartland theory suggests that whoever controls Eurasia could control the world, a theory which is renowned for its great influence on policy-makers.

Britain as the dominant naval power in the 19th century attempted to control Eurasia from the maritime periphery, which resulted in a prolonged conflict with Russia as the leading land power aspiring for hegemony from the centre of Eurasia. In the 20th century, the US, pursuing dominance from the maritime periphery of Eurasia, rivalled the Soviet Union, the dominant Eurasian land power. In the 21st century, Eurasian geopolitics have transformed as US maritime dominance is confronted with a multipolar Eurasia.

19th Century: British Maritime Power Versus Russian Land Power

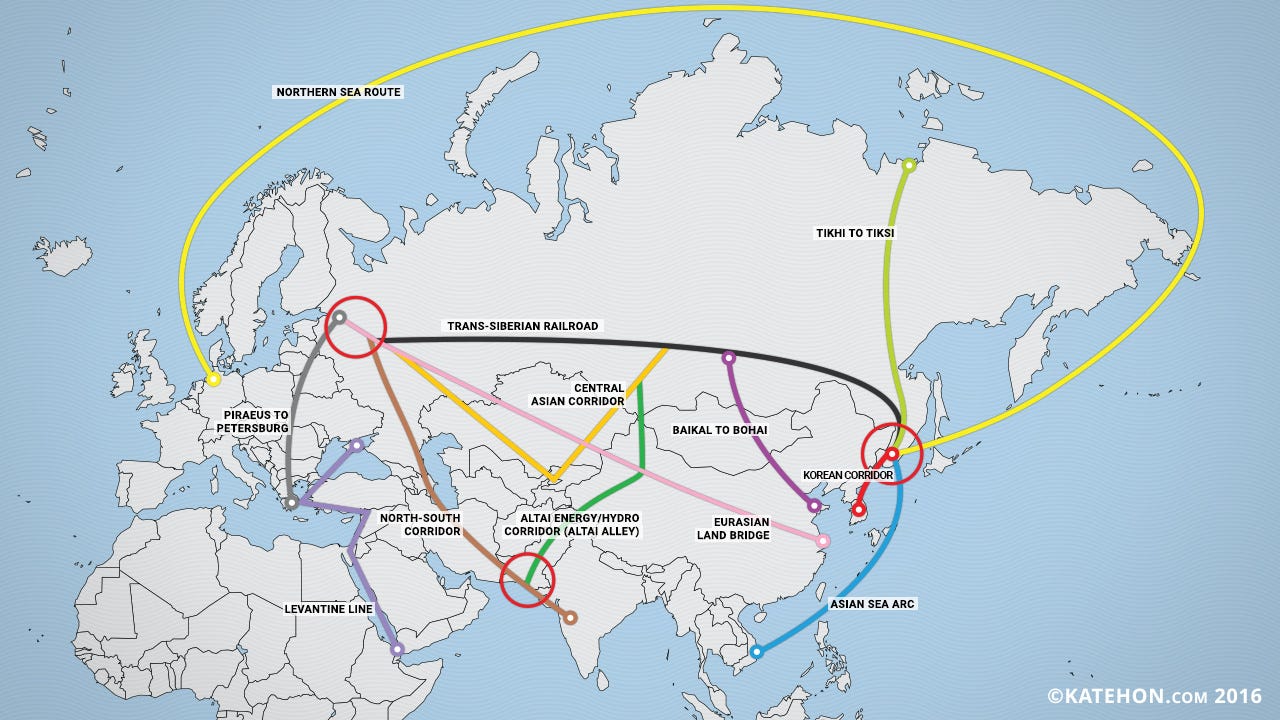

The ancient Silk Road connecting Eurasia was decentralised, connected by a myriad of land and sea corridors. Once it collapsed, the world was reconnected by European maritime powers from the early 16th century. Control over maritime corridors has always had an economic and military significance as the oceans are the arteries of international trade and are used to wield military power. The start of the 16th century thus marked the beginning of European empires. The defeat of Napoleon ended the British-French rivalry over controlling the seas, resulting in a century of British maritime dominance.

Russian history has largely been defined by a struggle to gain reliable access to the seas, before discovering the advantages of positioning itself as a Eurasian land power. With the collapse of Kievan Rus in the 13th century, the Russians lost access to the Dnieper River and other maritime transportation corridors. Russia’s victory over Sweden in the Great Northern War of 1721 marked its “return to Europe” as Russia obtained a dominant presence on the Baltic Sea, thus becoming a major maritime power, a great European power, and officially an empire.

Maritime powers seeking to weaken and contain Russia could threaten its reliable access to the seas. For example, the objective of the British and French in the Crimean War (1853-56) was to sever Russia’s connection with the Black Sea to push the country back into Asia and end its role as a European power. The renowned American naval strategist Nicholas Spykman (1942: 182) wrote in 1942:

“For two hundred years, since the time of Peter the Great, Russia has attempted to break through the encircling ring of border states and the reach the ocean. Geography and sea power have persistently thwarted her”.

The ability of the British to dominate the seas was key to its empire. Yet, the expansion of Russia as a land-power from the centre of Eurasia to the maritime periphery became a key threat to British dominance. In the early 19th century, Russian expansion towards the Ottoman Empire and Persia caused clashes with the British. Following the Crimean War, Russia built railroads through Central Asia which threatened to connect it with British India. The subsequent Russia-Britain conflict became known as the Great Game and was eventually resolved in 1895 with a border agreement in Afghanistan as a buffer between the British Empire and the Russian Empire.

In the last decade of the 19th century, Russia constructed the trans-Siberian railroad to the Pacific Ocean, thus also challenging British imperial interests in East Asia. Rather being an economically backward state at the periphery of Europe, without reliable access to the seas, Russia under Sergey Witte aspired to connect the vast Eurasian continent.

Mackinder developed the theoretical framework for how the control over Eurasia and the world would be determined by a rivalry between Britain as a maritime power and Russia as a land power. Mackinder (1904: 434) cautioned that the economic and military advantage of maritime empires due to their mobility on the seas was only temporary:

“Steam and the Suez Canal appeared to have increased the mobility of sea-power relatively to land-power. Railways acted chiefly as feeders to ocean-going commerce. But transcontinental railways are now transmuting the conditions of land-power and nowhere can they have such effect as in the closed heartland of Euro-Asia”.

American Maritime Power Versus Soviet Land Power

The US became a major maritime power in the late 19th century in accordance with the recommendations of Alfred Thayer Mahan. The victory in the American-Spanish War of 1898 resulted in the US acquiring colonial territories in the Americas and the Pacific Ocean. After the First World War, the Americans and British were preparing for war over primacy of the world seas. However, such as war was averted with Britain weakened after the Second World War, and the emergence of a powerful Soviet land power that was required to be balanced. The US subsequently replaced Britain as the dominant maritime power and established control over key maritime choke points.

The influential American naval strategist Spykman outlined a strategy for dominating Eurasia from the periphery (Western Europe, the Middle East and East Asia) as the foundation for dominance. Britain was considered an important node in the American Empire to control the Western edge of the Eurasian continent, and Spykman argued that the US would have “to adopt a similar protective policy toward Japan” to control the Eastern edge of Eurasia. John Foster Dulles, the US Secretary of State between 1953 and 1959, called for strengthening “island chains” with US allies such as Japan, Philippines and Australia to encircle and contain both China and the Soviet Union in the Pacific Ocean.

Mackinder’s ideas of dividing Eurasia to rule it from the maritime periphery came to dominate US strategic thinking. The US National Security Strategy of 1988 outlined the enduring relevance of Eurasia:

“The United States’ most basic national security interests would be endangered if a hostile state or group of states were to dominate the Eurasian landmass- that area of the globe often referred to as the world’s heartland. We fought two world wars to prevent this from occurring. And, since 1945, we have sought to prevent the Soviet Union from capitalizing on its geostrategic advantage to dominate its neighbors in Western Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, and thereby fundamentally alter the global balance of power to our disadvantage”.

Post-Cold War Global Primacy

After the Cold War, the US pursued a security strategy of global dominance. In the State of the Union address in January 1992, one month after the collapse of the Soviet Union, President Bush announced: “By the grace of God, America won the Cold War… the leader of the West that has become the leader of the world”.

The leaked draft of the Defense Planning Guidance (DPG) of February 1992 outlined that the endurance of US global dominance relied on preventing future rivals from emerging in Eurasia. In the language of Mackinder, the DPG document recognised that “It is improbable that a global conventional challenge to US and Western security will re-emerge from the Eurasian heartland for many years to come”. Defending the unipolar moment meant that the “first objective is to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival”, which included preventing allies and frontline states such as Germany and Japan from rearming.

Brzezinski, in his influential work on how to advance unipolarity, outlined the following strategy for how to preserve US dominance: “prevent collusion and maintain security dependence among the vassals, to keep tributaries pliant and protected, and keep the barbarians from coming together”.[7] Brzezinski described Russia as a geopolitical “black hole” in Eurasia, destined to a diminishing relevance. Russia did not have any other possible partners than the West, which “provided the West with a strategic opportunity. It created the preconditions for the progressive geopolitical expansion of the Western community deeper and deeper into Eurasia”.

NATO expansion incrementally reduced Russia’s reliable connectivity to all maritime corridors along its Western coast: the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and the Arctic. Greater ambitions included a “New Great Game” by severing Russia from Georgia, Ukraine, the Caspian Sea and Central Asia. The US version of a Silk Road project envisioned decoupling Central Eurasia from Russia and China.

However, NATO failed to seize Crimea and use Ukraine to expel Russia from the Black Sea. An energy corridor through Georgia and the Caspian could enable the West’s access to Central Asia. Georgia has warned it will not be used as a frontline against Russia, and is pursuing a more pragmatic relationship with its neighbour in the north. The planned TAPI pipeline (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India) also intended to contain Russia and China in Eurasia. Yet, the failure of the NATO occupation of Afghanistan disrupted progress on the TAPI pipeline.

American Unipolarity versus Eurasian Multipolarity

Unlike the rivalries of the past centuries between a hegemonic maritime power and a hegemonic land power, the current conflicts in Eurasia are defined by unipolarity versus multipolarity.

China’s New Silk Road, largely enabled by its strategic partnership with Russia, reduces the significance of US naval dominance. China develops new land- and sea corridors with its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Russia similarly develops an East-West corridor, the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) in cooperation with Iran and India, and the Northern Sea Route (NSR) through the Arctic. Other states on the Eurasian continent pursue similar initiatives to physically connect the Eurasian continent. The physical connectivity is supported by cooperation to develop alternative tech hubs, strategic industries, development banks, payment systems, commodity exchanges, trade in national currencies, and other economic connectivity.

The multipolar distribution of power incentivises the major powers to harmonise their interests. Not even China has the capability or intention to impose a hegemonic system, which creates a “balance of dependence”. Russia is comfortable with China being the leading economy in Eurasia, but it will not accept Chinese dominance and hegemony. Russia thus diversifies its economic connectivity across Eurasia to avoid excessive dependence on China. A hegemonic China would seek to sever ties between other centres of power, for example between Russia and India. However, China instead supports multipolarity and facilitates them in institutions such as BRICS and the SCO. China is also explicit that all countries must be allowed to pursue their own path to development, which contrasts with the universalist rhetoric of an aspiring hegemonic power.

In a rivalry between unipolarity and multipolarity, the global majority prefers the latter. US global primacy is advanced through peacetime alliances that perpetuate conflicts. US-led bloc politics serve the purpose of dividing for example China and India, the Arabs and Iran, Europe and Russia, in order to divide the world into dependent allies versus weakened adversaries. The disastrous consequences of reviving bloc politics in Europe by expanding NATO is not considered a cautionary tale, but a model to be exported to other parts of the world.

In contrast, a multipolar Eurasia enables states to pursue a multivector foreign policy and diversify economic connectivity, as a requirement for greater political autonomy. A multipolar Eurasia offers genuine multilateralism as opposed to confrontational bloc politics. The Chinese are not pressuring states to choose between “us” and “them”, they do not speak in the language of ultimatums, and thus are a more favourable partner. Countries around the world embrace multipolar institutions such as BRICS as it is anti-hegemonic, but do not want to join an anti-Western grouping. The purpose of multipolarity is to end bloc politics, not to create rival blocs.

It is worth citing Adam Smiths views on the concentration of power as the world was connected by European maritime powers. Smith referred to the discovery of America and the passage to the East Indies as the “two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind” by connecting the world. However, the concentration of power resulted in dominance and subsequent tragedy:

“To the natives however, both of the East and West Indies, all the commercial benefits which can have resulted from those events have been sunk and lost in the dreadful misfortunes which they have occasioned. These misfortunes, however, seem to have arisen rather from accident than from anything in the nature of those events themselves. At the particular time when these discoveries were made, the superiority of force happened to be so great on the side of the Europeans that they were enabled to commit with impunity every sort of injustice in those remote countries”.

Smith expected that a more benign and just world could emerge under a more evenly distributed balance of power:

“Hereafter, perhaps, the natives of those countries may grow stronger, or those of Europe may grow weaker, and the inhabitants of all the different quarters of the world may arrive at that equality of courage and force which, by inspiring mutual fear, can alone overawe the injustice of independent nations into some sort of respect for the rights of one another. But nothing seems more likely to establish this equality of force than that mutual communication of knowledge and of all sorts of improvements which an extensive commerce from all countries to all countries naturally, or rather necessarily, carries along with it”.

Eurasian Mulitpolarity as a Model for the West

The US will not succeed in restoring global primacy, although it can benefit greatly from accepting a more modest role in a multipolar system. The era of unipolarity has evidently already come to an end, and efforts to restore it merely create incentives for the world to decouple from the US. The new format for Eurasian security thus offers opportunities for the US. If Washington accepts a more modest role in the world, as one of several great powers in a multipolar system, it can avoid exhausting its resources and incentivise collective balancing.

The US has historically pursued an offshore balancer strategy to preserve a balance of power on the Eurasian continent. As a maritime power, the US could preserve its strength and only enter wars on the continent after the other powers had already exhausted themselves, and then the US would impose a settlement that preserved the balance of power. Establishing itself on the continent and pursuing land wars such as Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan would merely exhaust the US and result in collective balancing by other great powers. Eurasia now has multipolarity and the main powers would only form an anti-American coalition in opposition to US hegemony.

Eurasian multipolarity can also resolve the conflicts in Europe. The ambition to overcome bloc politics towards the end of the Cold War failed. Inclusive pan-European security agreements were instead abandoned in favour of expanding an exclusive military alliance that revived the zero-sum logic of the Cold War. Consequently, Europe is fighting over where to draw the new militarised dividing lines, resulting in the continent becoming less prosperous, more dependent and less relevant. The EU’s objective of a US-EU collective hegemony has been replaced with subordination as the Europeans retreat under US protection rather than diversifying economic connectivity and ending bloc politics. The EU can still change course by embracing a Eurasian model for Europe in which exclusive military blocs are replaced with inclusive multipolar arrangements.

Be the first to comment